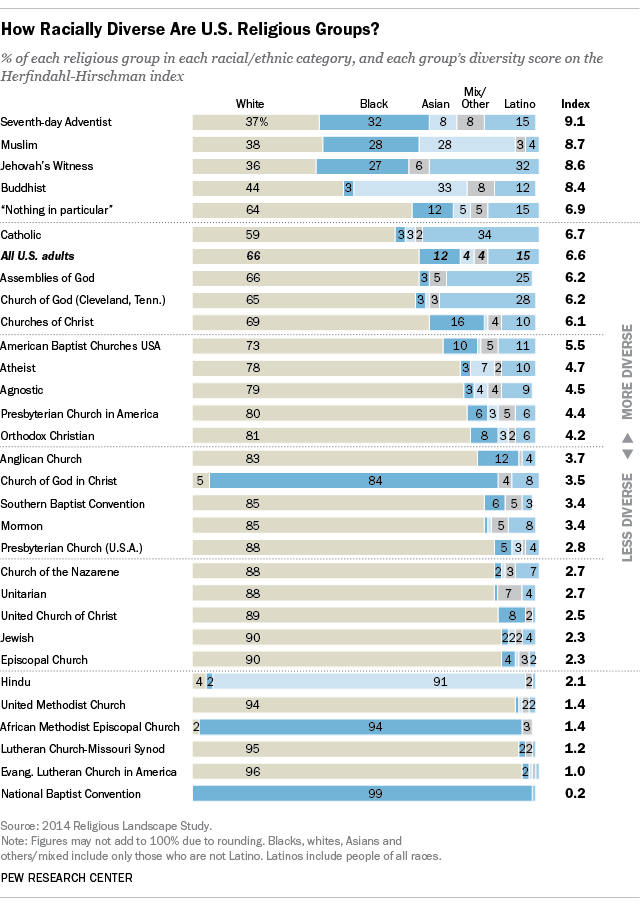

How diverse are America’s religious groups and denominations? Pew Research recently attempted to answer that question and provides the data in a handy infographic:

The graphic seems to show at a glance that some denominations, such as the Seventh-Day Adventist, include a relatively balanced mix of racial and ethnic groups, while others, such as the National Baptist Convention, are racially and ethnically homogenous. But the chart doesn’t tell us as much about diversity in denominations as it might appear. And it would be a mistake to use such data to make assumptions about what levels of diversity there should be in America’s denominations.

Before we examine those claims, let’s clarify what an average or baseline level of diversity would presumably look like. The most obvious standard, and the one many people implicitly use, is what we could call a “census quota”—each racial and ethnic group should be represented within denominations in percentages that correspond to their representation in the broader U.S.

According to Pew Research, those percentages for all U.S. adults are: White (non-Latino), 66 percent; Black, 12 percent; Latino, 15 percent; Asian, 4 percent; Mix/Other, 4 percent. Based on the census quota standard, the Churches of Christ would have the closest to the “ideal” level of diversity. No other group even comes close to having such a preferred “balance.”

We might assume that when it comes to diversity the Churches of Christ are doing something right and everyone else is doing something wrong. And that may well be the case. But it’s more likely that we are simply using the flawed method of measurement. The census quota metric may not only be the wrong gauge for denominational diversity it could, if implemented, lead to outcomes that would be rejected by black Americans.

Take another look at the chart and think about what would be required to achieve census quota parity between just two groups: white and black Christians. In most denominations, whites are overrepresented. We wouldn’t want them to leave these denominations (except maybe the apostate one) so we’d need to “dilute” their percentages by increasing the percentage of minorities.

For example, let’s say for the sake of simplicity that there were only 99 people in the Southern Baptist Convention: 85 whites, 6 blacks, 3 Latino, and 5 mixed. Their percentages within the SBC would also be 85 percent, 6 percent, 3 percent, and 5 percent. If we added 7 more black members to the denomination, there would still be a lot of whites (79 percent) but the percentage of blacks would reach census quota (12 percent).

But where would those 7 additional black members come from? We’d either need to bring them from another denomination that has more than 12 percent black members, from the un-churched, or from non-Christian religious groups.

If we’re doing this exercise for only one denomination, we may not have any problems achieving our intended racial mix. We could easily find enough members and not make any other denominations less diverse. But what happens when we try to make all Christian denominations more diverse by increasing their percentage of black members? Eventually we’d need to lure away members from the groups that have the most black members to “spare”: the Church of God in Christ, the African Methodist Episcopal Church, and the National Baptist Convection.

As you might imagine, increasing diversity by “sheep stealing” from predominantly black denominations is a solution that many black Americans—even those who don’t attend those denominations—would find offensive. Yet therein lies the problem for increasing diversity in the other denominations. There is simply not a large enough number of black Americans to have both census quota diversity and large, predominantly black denominations.

This is not to say that increasing diversity within denominations should not be a goal. It also does not imply that local churches should use this as an excuse for not trying to increase outreach to minorities. Local churches have the ability to increase diversity in ways that may not be achievable at the denominational level.

But what such rudimentary analysis can show is that we need a more sophisticated way of determining just what diversity in denominations would look like. We can’t assume, for instance, that just because 12 percent of the population is black that 12 percent of our denominations should be comprised of black members. We also can’t automatically take pride in the fact that our denomination may be more diverse than another denominations, since the comparisons may obscure relevant factors.

If increasing diversity within our denominations is a goal—and I believe it should be—we need to come up with more advanced metrics that can help us determine exactly what a realistic level of diversity would look like. That will require more number-crunching and analysis of regional demographics than we are used to doing. But it may be the only way to truly determine both whether a denomination’s minority outreach is effective and whether they are becoming more diverse.

Are You a Frustrated, Weary Pastor?

Being a pastor is hard. Whether it’s relational difficulties in the congregation, growing opposition toward the church as an institution, or just the struggle to continue in ministry with joy and faithfulness, the pressure on leaders can be truly overwhelming. It’s no surprise pastors are burned out, tempted to give up, or thinking they’re going crazy.

Being a pastor is hard. Whether it’s relational difficulties in the congregation, growing opposition toward the church as an institution, or just the struggle to continue in ministry with joy and faithfulness, the pressure on leaders can be truly overwhelming. It’s no surprise pastors are burned out, tempted to give up, or thinking they’re going crazy.

In ‘You’re Not Crazy: Gospel Sanity for Weary Churches,’ seasoned pastors Ray Ortlund and Sam Allberry help weary leaders renew their love for ministry by equipping them to build a gospel-centered culture into every aspect of their churches.

We’re delighted to offer this ebook to you for FREE today. Click on this link to get instant access to a resource that will help you cultivate a healthier gospel culture in your church and in yourself.