Genre: Various Proposals

The genre of Jonah is debated. The book has been read as an allegory, using fictional figures to symbolize some other reality. According to this interpretation, Jonah is a symbol of Israel in its refusal to carry out God’s mission to the nations. The primary argument against this view is that Jonah is clearly presented as a historical and not a fictional figure (see the specific historical and geographical details in Jonah 1:1–3; 3:2–10; 4:11; cf. also 2 Kings 14:25). Another proposal is that the book is a parable to teach believers not to be like Jonah. Like allegories, parables are also based on fictional and not historical characters. Parables, however, are typically simple tales that make a single point, whereas the book of Jonah is quite complex and teaches a multiplicity of themes.

The book of Jonah has all the marks of a prophetic narrative, like those about Elijah and Elisha found in 1 Kings, which set out to report actual historical events. The phrase that opens the book (“the word of the Lord came to”) is also at the beginning of the first two stories told about Elijah (1 Kings 17:2, 8) and is used in other prophetic narratives as well (e.g., 1 Sam. 15:10; 2 Sam. 7:4). Just as the Elijah and Elisha narratives contain extraordinary events, like ravens providing bread and meat for the prophet (1 Kings 17:6), so does the book of Jonah, as when the fish “provides transportation” for the prophet. In fact, the story of Jonah is so much like the stories about Elijah and Elisha that one would hardly think it odd if the story of Jonah were embedded in 2 Kings right after Jonah’s prophetic words about the expansion of the kingdom. The story of Jonah is thus presented as historical, like the other prophetic narratives.

There are additional arguments for the historical nature of the book of Jonah. It is difficult to say that the story teaches God’s sovereignty over the creation if God did not in fact “appoint” the fish (Jonah 1:17), the plant (Jonah 4:6), the worm (Jonah 4:7), and the east wind (Jonah 4:8) to do his will. Jesus, moreover, treated the story as historical when he used elements of the story as analogies for other historical events (see Matt. 12:40–41). This is especially clear when Jesus declared that “the men of Nineveh will rise up at the judgment with this generation and condemn it, for they repented at the preaching of Jonah” (Matt. 12:41).

The story of Jonah is not, however, history for history’s sake. The book is clearly didactic (as the allegorical and parabolic interpretations rightly affirm); that is, the story is told to teach the reader key lessons. The didactic character of the book shines through in the repeated use of questions, 11 out of 14 being addressed to Jonah, and the question that closes the narrative leaves readers asking themselves how they will respond to the story.

Genre: Literary Features

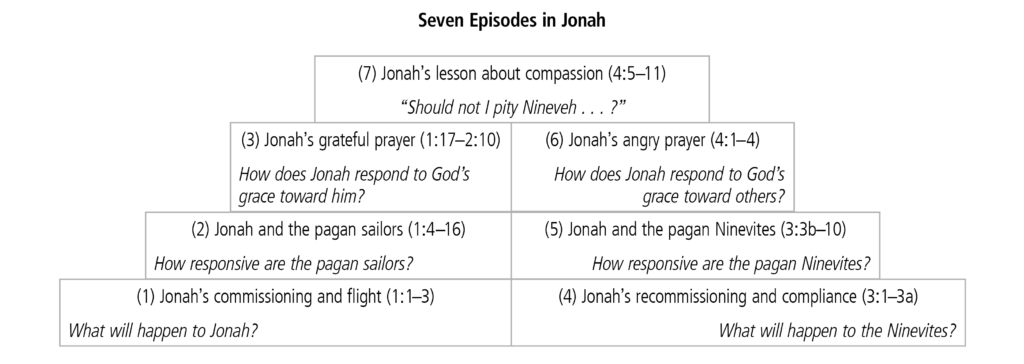

The book of Jonah is a literary masterpiece. While the story line is so simple that children follow it readily, the story is marked by as high a degree of literary sophistication as any book in the Hebrew Bible. The author employs structure, humor, hyperbole, irony, double entendre, and literary figures like merism to communicate his message with great rhetorical power. The first example of this sophistication is seen in the outline of the book (see below).

The main category for the book is satire—the exposure of human vice or folly. The four elements of satire take the following form in the book of Jonah:

- The object of attack is Jonah and what he represents—a bigotry and ethnocentrism that regarded God as the exclusive property of the believing community (in the OT, the nation of Israel);

- The satiric vehicle is narrative or story;

- The satiric norm or standard by which Jonah’s bad attitudes are judged is the character of God, who is portrayed as a God of universal mercy, whose mercy is not limited by national boundaries;

- The satiric tone is laughing, with Jonah emerging as a laughable figure—someone who runs away from God and is caught by a fish, and as a childish and pouting prophet who prefers death over life without his shade tree.

Three stylistic techniques are especially important.

- The giantesque motif—the motif of the unexpectedly large (e.g., the magnitude of the task assigned to Jonah, of the fish that swallows him, and of the repentance that Jonah’s eight-word sermon accomplishes).

- A pervasive irony (e.g., the ironic discrepancy between Jonah’s prophetic vocation and his ignominious behavior, and the ironic impossibility of fleeing from the presence of God).

- Humor, as Jonah’s behavior is not only ignominious but also ridiculous.

Taken from the ESV® Study Bible (The Holy Bible, English Standard Version®), copyright ©2008 by Crossway, a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers. Used by permission. All rights reserved. For more information on how to cite this material, see permissions information here.