The Story

Two recent surveys show that when it comes to religion in the public square, most Americans are more comfortable with civil religion than with Christianity.

The Background

A new study by Lifeway Research finds that 85% of Americans want to keep “under God” in the Pledge of Allegiance, including 94% of self-identified born again, evangelical, or fundamentalist Christian. Only 8% of Americans want to remove “under God” from the Pledge of Allegiance.

A related poll by Fairleigh Dickinson University finds that American voters accept prayer in official, public meetings. In the survey, 73% percent of voters say “prayer at public meetings is fine as long as the public officials are not favoring some beliefs over others.” Just one-quarter (23%) say “public meetings shouldn’t have any prayers at all because prayers by definition suggest one belief or another.”

(Note: The skewed poll question limits the usefulness of the findings. The question asked was, “Some say public meetings shouldn’t have any prayers at all because prayers by definition suggest one belief or another. Others say prayer at public meetings is fine as long as the public officials are not favoring some beliefs over others. Which comes closer to your view.” A third option should have been offered: Public prayers are fine even if they favor some beliefs over others.”)

Why It Matters

Jean Jacques Rousseau, who coined the phrase “civil religion” in his treatise, On the Social Contract (1762), made the observation that in ancient times all governments were a form of theocracy with each nation serving their own god. States, therefore, never had religious wars since the governments “made no distinction between its gods and its laws.” Rousseau finds the genius of the Roman Empire was its ability to absorb both the nations and their gods and transform them into one pagan religion. This changed, he claims, with the appearance of Christ:

It was in these circumstances that Jesus came to set up on earth a spiritual kingdom, which, by separating the theological from the political system, made the State no longer one, and brought about the internal divisions which have never ceased to trouble Christian peoples. As the new idea of a kingdom of the other world could never have occurred to pagans, they always looked on the Christians as really rebels, who, while feigning to submit, were only waiting for the chance to make themselves independent and their masters, and to usurp by guile the authority they pretended in their weakness to respect. This was the cause of the persecutions.

Rousseau claims that this division between religion and the state “made all good polity impossible in Christian States; and men have never succeeded in finding out whether they were bound to obey the master or the priest.” He believed that political leaders tried to restore this lost ideal but have been unsuccessful because of the influence of Christianity, which put devotion to God above that of the State. Since religious devotion is not only useful to the state but can become a hindrance to the state’s authority, a third way was needed—civil religion:

There is therefore a purely civil profession of faith of which the Sovereign should fix the articles, not exactly as religious dogmas, but as social sentiments without which a man cannot be a good citizen or a faithful subject. While it can compel no one to believe them, it can banish from the State whoever does not believe them—it can banish him, not for impiety, but as an anti-social being, incapable of truly loving the laws and justice, and of sacrificing, at need, his life to his duty. If anyone, after publicly recognizing these dogmas, behaves as if he does not believe them, let him be punished by death: he has committed the worst of all crimes, that of lying before the law.

The dogmas of civil religion ought to be few, simple, and exactly worded, without explanation or commentary. The existence of a mighty, intelligent and beneficent Divinity, possessed of foresight and providence, the life to come, the happiness of the just, the punishment of the wicked, the sanctity of the social contract and the laws: these are its positive dogmas. Its negative dogmas I confine to one, intolerance, which is a part of the cults we have rejected.

America has done a fine job of incorporating Rousseau’s “dogmas of civil religion,” keeping them “few, simple, and exactly worded.” We have restricted such sentiments to the most unobtrusive areas, allowing “In God We Trust’ to be printed on our coins and the phrase “under God” to slip in our Pledge of Allegiance (which, curiously, isn’t a pledge of “allegiance” to God but to a flag). We allow recognition for a “Divinity, possessed of foresight and providence” but what we don’t allow is the recognition of Jesus as God. And that is what should give Christians pause.

There is a vast and unbridgeable chasm between America’s civil religion and Christianity. If we claim that “under God” refers only to the Christian, Trinitarian conception of God we are either being unduly intolerant or, more likely, simply kidding ourselves. Do we truly think that the Hindu, Wiccan, or Buddhist is claiming to be under the same deity as we are? We can’t claim, as Paul did on Mars Hill, that the “unknown god” they are worshiping is the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. They have heard of Jesus—and reject him as God.

The Pledge is a secular document and the “under god” is referring to the Divinity of our country’s civil religion. Just as the pagan religion of the Roman Empire was able to incorporate other gods and give them familiar names, the civil religion provides an umbrella for all beliefs to submit under one nondescript, fill-in-the-blank term.

Don’t get me wrong: I think we need to stand firm on allowing religion into the “naked public square.” But we should do so defending our real religious beliefs rather than a toothless imitation. If we pray in the public square, we should have no qualms about using the true name of the God to whom we are praying.

Our God is a jealous God and is unlikely to look favorably upon idolatry even when it is put to good service. While we should be as tolerant of civil religion as we are of other beliefs, we should be cautious about submitting to it ourselves. That is not to say that we can’t say the Pledge or listen to a non-sectarian prayer and think of the one true God. But we should keep in mind that this fight over ceremonial deism isn’t our fight and the “god” of America’s civil religion is not the God who died on the Cross.

Is the digital age making us foolish?

Do you feel yourself becoming more foolish the more time you spend scrolling on social media? You’re not alone. Addictive algorithms make huge money for Silicon Valley, but they make huge fools of us.

Do you feel yourself becoming more foolish the more time you spend scrolling on social media? You’re not alone. Addictive algorithms make huge money for Silicon Valley, but they make huge fools of us.

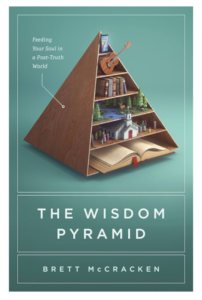

It doesn’t have to be this way. With intentionality and the discipline to cultivate healthier media consumption habits, we can resist the foolishness of the age and instead become wise and spiritually mature. Brett McCracken’s The Wisdom Pyramid: Feeding Your Soul in a Post-Truth World shows us the way.

To start cultivating a diet more conducive to wisdom, click below to access a FREE ebook of The Wisdom Pyramid.