In his new novel Birmingham, author and journalist Tim Stafford transports readers to the spring of 1963, to the “meanest city in the South,” and to Martin Luther King Jr.’s showdown with notorious commissioner of public safety Bull Connor.

The story alternates chapter by chapter between Chris Wright, a white seminary student from California, and Dorcas Jones, a young black woman fully dedicated to the civil rights cause. Readers shadow one or the other character as they picket and protest, endure time in Birmingham jails, meet with King, and stand toe-to-toe with the Ku Klux Klan. We hear Chris and Dorcas reflect on their emotional ups and downs. We listen to their frustrations and watch as both learn what it means to become a part of God’s redemptive plan.

Chris comes to town on a Greyhound bus—penniless, naïve, and too self-righteous for anybody’s liking. He’s left his wife and struggling marriage behind; he’s got no choice, he says, God has called him. Chris is certain he understands the toxic effects of segregation, and that he, unlike other white people, sees the toll this sin takes—not only on black people but also on the Klan and Bull Connor and George Wallace and Birmingham’s “big mules,” the business elites who push and pull the levers of power.

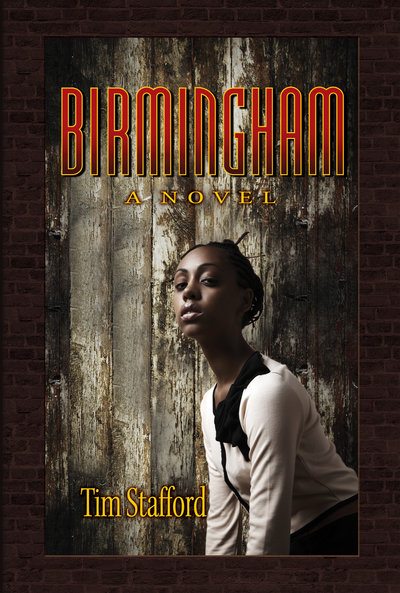

Birmingham: A Novel

Tim Stafford

In Chris, Stafford gives us a picture of a prophetic life. Like Jonah in Nineveh, Chris in Birmingham feels the unseen burden of oppressive sin. Unlike Jonah, however, Chris is eager to engage. He sees the danger and is drawn to it, willing to give his life and put righteousness ahead of his well-being. He’s convinced he, like Esther, was born for a time like this.

We find traces of Ezekiel and Isaiah, too. As the story progresses, Chris nurtures relationships with stalwarts of the white establishment, with civil rights leaders, even with a member of the Ku Klux Klan. He imagines himself as the go-between; the one man in Birmingham who—because of his race, education, and theological wisdom—is positioned to “stand in the gap” as the bridge from one camp to all the others. “Here I am,” he’s forever telling God, “send me.”

Key to Freedom

Dorcas, the female lead, has placed her hope in the civil rights movement and in R. L. Wriggleshott, its revered local leader. These hold the key to her freedom, and this is where her loyalty lies. She doesn’t like Chris and makes it unmistakably clear: she’s got no use for a privileged white guy mucking about in the movement’s business.

As we enter the story, the sit-ins and marches have borne little fruit, and Dorcas seethes impatiently. She’s spoiling for a fight. She wants to get arrested. She wants to be free, and she’s tired of waiting. Dorcas is soon captivated by a kindred spirit, Jerry Mealman, a handsome and brooding second-tier leader ready to “blow up the whole damn town” if that’s what it takes to provoke real change.

Through this edginess and anger, Stafford reveals a conflict in strategies. King and his top aid, Substance Petry, have brought the “science of non-violence” to Birmingham. Like Wriggleshott, Dorcas, and Jerry, they aim to transform society—but not by toppling their foes. They desire everyone—black and white—to live life abundantly. Therefore, they don’t grasp for power; they strive for the “beloved community.”

Dorcas and Jerry dismiss King’s idealism. Dorcas wants to do as she pleases. She wants to go where she wants to go and to “live in a big open space.” She wants to be free but has no heart for reconciliation.

As Dorcas and Jerry smolder, Wriggleshott finds a way to keep them busy. He orders Jerry to organize the children and prepare them to march, thereby filling the void left by a dearth of adult volunteers. So, reluctantly and inadvertently, Jerry becomes the leader of the Birmingham Children’s Crusade.

Meanwhile, Chris is drawn deeper into the movement. After weeks of being denied the chance, he finally marches—the only white man among a throng of protesters—and he feels the elation. “I felt no promise of triumph,” he remarks, “only a solemn, trance-like sense of going forward to my destiny.” When police halt the procession, Chris sinks to his knees, mimicking the woman beside him whose arms are held out “as if to catch an object thrown from above.” She’s praying the Lord’s Prayer, and Chris prays with her. It was, he says, the “most faith-filled instant of my life. I had no concern for myself, my future, my significance. I felt no fear.”

Birmingham could have used more of this description. Throughout the book I wanted Stafford to take me into the action. He so skillfully reveals Chris’s thoughts and gives us free reign to rummage around Dorcas’s mind and listen to her hard-edged contemplations. But I wish, instead of hearing their thoughts, I’d been involved in the events that provoked them.

Fact or Fiction?

There’s one other problem with the book, and that’s the way it blends fact and fiction. This is a story about Birmingham and Operation C (for “Confrontation”) and the children’s crusade. These are part of the country’s collective memory—events organized and executed by celebrated historical figures. It’s common knowledge Fred Shuttlesworth was the brains behind Operation C, not Wriggleshott. And it’s no secret James Bevel organized the children’s crusade, not Jerry Mealman. And where, in Stafford’s story, Chris is asked to edit and type King’s letter from a Birmingham jail, we know it was Wyatt Walker, a King confidant, who actually puzzled these scraps together.

We come to fiction happy to suspend our disbelief, but these inconsistencies jumble the reader’s mind. Why is King there, but Shuttlesworth isn’t? Why did Stafford include Bull Connor but not James Bevel? And why does Substance Petry (and Chris) replace Wyatt Tee Walker? These incongruities distract us from a good story.

Nevertheless, Birmingham is worthwhile. We love fiction, in part, because we revel in the language and wallow in deftly crafted paragraphs, one sentence woven into the next, propelling our escape into a world of the author’s making. Stafford’s prose not only delights, it also provides a window into a world many of us don’t know, or have long forgotten.

This is a book about peace—not the mere absence of conflict, but shalom—the peace that comes from meaningful reconciliation among individuals, races, classes, and institutions. It’s about freedom—not to do whatever we want, but freedom to love and forgive and find meaning in something beyond ourselves. It’s also about purpose. Chris sees oppression, injustice, and inequality before the law. But these don’t drive him away from Birmingham; they compel him to enter the city, become an agent of renewal, and forge the “beloved community” God intended.

Stafford is a terrific writer, and his novel serves fiction’s prophetic purpose: to tell a gripping story, and with it, to reveal the distance between “what is” and “what ought to be.”