More than 20 years ago, Olan Stubbs was trying to share his faith with two guys in his freshman class at Samford University in Birmingham, Alabama. It wasn’t working.

One sat on the dorm steps outside and smoked weed. When Stubbs attempted to explain verses to him, he said he didn’t believe the Bible. The other was a football player “who could articulate the gospel better than I could. But he was often coming in late at night, drunk. Obviously there was some kind of disconnect.”

Stubbs didn’t know what to say or do. Then he heard about two RAs on the second floor who were leading a Bible study. They’d led someone he knew to Christ.

“I’d love to learn how to share my faith like you guys are doing,” he told them. They handed him a booklet by Navigators founder Dawson Trotman and told him to “get involved in Campus Outreach.”

Campus Outreach was famous for its evangelism, founded by a church famous for its evangelism, planted by a man famous for his evangelism.

Stubbs was hooked. Today, he’s one of nearly 750 Campus Outreach staff serving on 122 campuses in 11 countries. In its 40 years, Campus Outreach has seen 55,000 students at evangelistic events. Staff and volunteers have discipled 15,000 students over weekly Bible studies and worship times—1,447 of them have gone on to serve in ministry or missions. Over the last 12 months alone, 712 students have professed their faith in Christ.

Campus Outreach staff and volunteers have discipled 15,000 students over weekly Bible studies and worship times—1,447 of them have gone on to serve in ministry or missions.

Stubbs works at Briarwood Presbyterian Church, where Campus Outreach began. The church was planted in 1960 and grew to 4,000 members largely on the strength of personal evangelism. “The Great Commission has been our heartbeat,” the website says, and it’s not kidding: Briarwood partners with more than 100 mission boards and organizations and more than 300 ministry staff.

Briarwood got that heartbeat from its founder.

“If you meet a Christian in Birmingham who is 60 or older, and you ask them how they came to Christ, I’d bet my money that at some point they’ll mention Frank Barker,” Stubbs said.

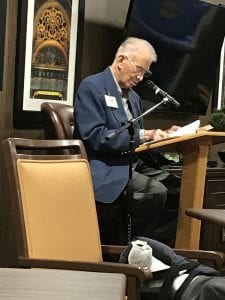

The 86-year-old Barker has led many thousands to Christ—his daughter Peggy Townes estimated 10,000 personally and hundreds of thousands through his ministries. But it wasn’t because he loved talking to people. He’s not a gregarious personality or even a compelling speaker.

“I’d like to just settle in and read a book,” he said. “But the Bible tells us to reach out to others, so I had to discipline myself to do that.”

Turns out, that was catching.

Later to Faith than to Ministry

Barker came to ministry late, and to faith even later.

Beginning in high school, “I was living a pretty wild life morally,” Barker told TGC. From lying to his parents to throwing eggs at people to drinking too much (and then driving), Barker knew he wasn’t living a good life, but couldn’t pull himself out of it.

Playing tennis restricted his rowdiness, but not a lot and not for long. He went to college on an ROTC scholarship, then became a jet pilot in the United States Navy.

One weekend, while in flight training school, “I came back up to Birmingham and had a wild weekend,” Barker said.

On his way back to Pensacola, he fell asleep at the wheel, and when the road curved, his car sped onto a rutted-out dirt road. When he finally got the car stopped, the headlights picked up a sign nailed to a tree: “The wages of sin is death.”

“I thought, You know what? I think God is trying to tell me something,” he said. “I started trying to straighten up. I felt I’d been so bad that if I was going to get to heaven, I was going to need to be a preacher.”

Barker kept swinging between resolving to do better and partying until one night, when he felt God was actually listening to the rote prayer he tossed up. He told God he wanted to follow him.

Barker began to stay home from the wild nights with his friends; after his tour of duty, he enrolled at Columbia Theological Seminary. A month in, he inherited from his roommate a preaching gig at an Alabama church.

“The first year, nothing particularly good happened,” he said. “At the end of that year, I thought, Something’s wrong. I wonder if I’m really a Christian.”

It was an awkward question to ask his professors or congregants, but he knew an Air Force chaplain, and asked him. (“Joe, how can I make sure I’m a Christian?”)

The chaplain gave Barker a tract and told him to put his trust in Jesus and receive salvation as a gift.

“That’s wrong,” Barker told him. “God’s not going to just give this thing away! You’ve got to work for it.”

The chaplain insisted, and Barker began to realize “I had totally missed that salvation was about grace. I surrendered my will and transferred my trust from me to Christ. When I did that, life began to change dramatically.”

Storefront Church

Among the first people Barker tried to evangelize were his parents, who were already saved. Then he told his sister, who accepted Christ. He told the handyman. He told his friends. He told his congregation, which began to grow.

After seminary, the Birmingham presbytery of the Presbyterian Church in the United States asked Barker if he’d organize a new church in the rapidly developing area of Cahaba Heights.

Intent on a PhD, he told them no.

They asked for the summer.

Just the summer, he agreed.

Barker knocked on doors and found so much interest in a new congregation that he skipped the Bible study stage of church planting and went right to the rented building, setting up in an old barber shop in a strip mall. That first Sunday, 70 people showed up. Three months in, Briarwood Presbyterian Church was chartered with 90 members.

Barker packed out the storefront church. Three years in, with 290 members, Briarwood moved into its own facility that could fit 400. (It was there the Presbyterian Church in America held its first meeting in December 1973.) A few years later, a 1,000-seat sanctuary was added.

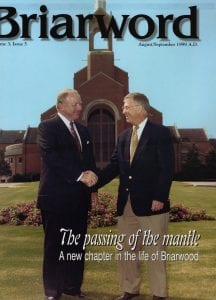

In 1988, Briarwood moved into a facility that could fit 4,000. By the time Barker retired in 1998, membership had grown that large.

But they weren’t necessarily drawn in by the preaching.

‘Kind of Boring’

“My father was not a dynamic orator by any means,” Townes said. “He’d shuffle up to the pulpit and say, ‘Uh, turn in your Bibles to 1 John 3,’ and then quietly read it and start preaching. There was nothing dynamic or big about it.”

“When I first visited Briarwood as a freshman in college, I was like, ‘This guy’s kind of boring,’” Stubbs said.

But Barker had the zeal of a new convert and the discipline of a Navy pilot.

“I had to train myself” to evangelize, Barker said. “You know, you get on an airplane thinking about the person you’re going to be sitting next to.”

At first, he didn’t know how to share his faith—“I didn’t learn it in seminary”—so he just kept telling the story of his own conversion.

“A lot of people in the 1960s could really identify with that, because they had a religious worldview: ‘There is a God, and I’m supposed to be a good person,’” Stubbs said.

“Religion was very accepted, but such a private thing,” Townes said. “And then all of a sudden there were people who had grown up in religious homes and religious society saying they’d become Christians. . . . Adults who’d always thought they were Christians because they were moral people were suddenly being transformed by the gospel. It was an explosion.”

Though some who came to Briarwood were already Christians, most “joined because Frank led them to Christ,” said National Christian Foundation Alabama president Tom Bradford, who has been friends with Barker for 50 years. (They still play tennis together three days a week.)

“He was not only evangelistic, but real strong in Bible teaching and small groups,” Bradford said. “He was teaching probably five or six Bible classes a week himself.” (At one of those Bible studies, Barker led Bradford to Christ.)

Two nights a week, the Bible studies were at Barker’s house. “I’m talking anywhere from 15 to 60 people,” Townes said. “People were everywhere—sitting on the floor.”

Barker would lead the Bible study; his wife, Barbara, would sing; and someone would share their testimony. “We trained people to do that using Campus Crusade and Evangelism Explosion,” Barker said. “Every Wednesday night we would have evangelism training, and then go out and call on people.”

The conversions built on each other—as nonbelievers came to Christ, excitement grew. “I was 29 when I came to Christ, and so excited about my newfound faith that it was easy for me to talk to people about it,” Bradford said.

As he and others watched Barker—and then each other—share testimonies and talk about the gospel, they began to do it too.

“There was just a culture at Briarwood that if you came to Christ, you started sharing your faith,” Stubbs said.

Barker’s testimony, in particular, kept growing.

50-50 Rule

Barker grew up in an influential Birmingham home, but decided before he was married that he’d make “what any financial adviser would say were very foolish financial decisions,” Townes said. “He decided he would give in such a way that he had to live by faith. We grew up knowing we didn’t go to Mom or Dad for our needs. We went to the Lord.”

Every year, Barker increased the percent of his salary he was giving to God. His stories of financial providence—the gift of a car when his broke down, checks arriving in the nick of time—sound like those of George Müller, who cared for thousands of orphans in 19th-century England without ever asking for money or going into debt.

Barker told those stories to Briarwood, which thrilled to God’s providence and followed Barker into radical giving. The church set up a 50–50 rule, where every dollar spent on Briarwood would be matched by another spent on outside ministries.

It took them seven years to get there. But since then, Briarwood has hit that goal almost every year. Some years, it even exceeds it. (“We don’t do a savings-and-loan thing and carry money over to the next year,” current Briarwood senior pastor and TGC Council member Harry Reeder said. “Instead, we take any excess giving and do special outreach projects.”)

In addition, Barker began taking an annual global mission offering. Last year at Briarwood, that $2.7 million offering funded about 250 missionary families and agencies in 68 countries. Those missionaries shared the gospel more than 182,000 times, led almost 40,000 people to Christ, and planted or worked to revitalize almost 700 churches.

The global missions offering is on top of the regular tithing, which supports local, regional, and national missions.

Staff used to joke that “the strength and weakness of Barker is that anybody could walk into his office with any vision to reach lost people—say, to reach left-handed people—and Rev. Barker would say, ‘Great. Let’s get you some money and try it,’” Stubbs said.

That’s how Briarwood ended up with more than 120 ministries, Stubbs said. “Some exceeded expectations, some didn’t.”

A handful were enormously successful—the ballet school started by Barbara, a Christian school, a seminary, a summer camp for children, a medical professionals ministry, a business leaders ministry.

And Campus Outreach.

40 Years Old

Campus Outreach was born out of answered prayer—but not Barker’s. Uncharacteristically, he had no faith that God would save Tom Caradine.

“I was disgusted with [Tom],” Barker said with a small, self-deprecating smile. “But my wife really cared for him.”

Barbara would buy handkerchiefs once a month from the clothing store where the teen worked; he’d call her to talk about girlfriend problems.

“Only problem was, it would be 2 a.m. in the morning and he’d be drunk,” Barker remembered.

“When are you going to quit wasting time with that no-good bum?” Barker asked his wife.

“He’s going to become a Christian,” she told him.

“No, he’s not.”

“I’m praying for him.”

“That one will not be answered,” Barker recalled saying, chuckling at himself. “How’s that for spiritual attitude?”

Caradine did become a Christian—and let the Barkers know with a late-night phone call. His senior year, he began reaching out to his classmates at Samford. After graduation, he and classmate Curtis Tanner came on staff at Briarwood as pastors to the campus. They called it Campus Outreach.

The two branched out to other schools in Alabama; in 1988, they left the state and started a franchise in Georgia. Now Campus Outreach is as far north as Bethlehem Baptist Church in Minneapolis and as far east as Capitol Hill Baptist Church in Washington, D.C.; its 18 international campuses stretch from New Zealand to Peru.

“Personal evangelism is what made Rev. Barker so effective, and by God’s grace we’ve been able to maintain that in Campus Outreach,” Stubbs said. He ran into that as a freshman, when he got on the bus for his first Campus Outreach conference and the student next to him immediately began sharing his faith.

“I was like, ‘Hey, that’s great. The whole reason I’m here is to learn how to share my faith,’” Stubbs said. He and the other student spent their free time at the conference practicing sharing their faith with strangers.

Another way Campus Outreach looks like Barker is its commitment to the local church. The chapters of Campus Outreach aren’t formally connected; each does its own work completely under the authority of a local church near a university. Campus Outreach Birmingham starts new chapters with seed money and staff, then backs itself out as the church gradually takes over.

Barker did the same thing, but with people.

“Mrs. Barker used to get frustrated because Rev. Barker would lead people to Christ, and then they’d go to a different church,” Stubbs said. Barker told her, “I’m not trying to build my church. I’m trying to build the kingdom.”

Barker was also generous with finances and access to donors. Often, when parachurch organizations approach pastors for help, most “don’t want to lose the time and money of their leaders,” Bradford said. “Frank would say, ‘Oh, man, that’s great. Let me give you some names.’”

Barker was even open-handed with Briarwood itself.

“He stepped down at 68 years old, when he was at the height of his ministry,” Townes said. “He saw other large churches where the senior pastor stayed a little too long. He said, ‘I don’t want to do that to Briarwood.’ A transition team was formed, and he completely submitted to them.”

Briarwood called Reeder, who had planted Christ Covenant Church in Charlotte out of Briarwood in 1983. Happy where he was, Reeder said no seven times before he said yes.

“Frank called me and said, ‘We want you to know that Barbara and I would be willing to move away from Birmingham’” if it would make the transition easier, Reeder remembers. Instead, Reeder asked him to stay as pastor emeritus.

“I’ve always told everyone, ‘If the Lord did not bless the transition, it would not be Frank’s fault,’” Reeder said. “Frank’s character and humility are such that I had no doubt he’d be supportive and encouraging. Not only has his presence not been a liability—it’s been an asset. I’ve always been grateful for that.”

Meat and Potatoes

Barker has “a genuine gospel-driven humility that is combined with an unrelenting trust in Jesus Christ to do the work,” TGC Council member emeritus Sandy Willson said. Willson discovered the secret to Barker’s ministry when rooming with him in a hotel once.

“When you’re his roommate, you see he’s a man of prayer,” Willson said. “If you want to know how a person who puts everything on the lower shelf, a person who doesn’t seem to be a sizzling orator, is used to grow a 4,000-member church—it’s God. It’s a man who knows God.”

When pastor Randy Pope was heading to Atlanta to plant Perimeter Church in 1977, Barker pulled him aside.

“He gave me some strong marching orders: ‘Don’t ever let a year in the life of your church go by that you are not personally equipping the people of your church to share their faith,'” Pope said. “It is the greatest advice I could have ever received.”

Willson also remembers getting counsel from Barker decades ago.

“The advice he gave me was basically: ‘Just have people over to your house for a covered-dish dinner and share the gospel with them and teach them the Bible,’” said Willson, chuckling at the simplicity. “A covered-dish dinner!”

It’s the advice Barker still gives.

“I would tell [young pastors] to begin to train [their congregations] in personal evangelism,” Barker told TGC this fall. “You can start small groups and meet in homes for Bible study, that type of thing. . . . Have everybody invite somebody. We did that for many years, and it worked pretty well.”

“There’s nothing exotic about Briarwood,” Reeder said. “We’re just meat-and-potatoes.”

And yet—there is a little bit of secret sauce.

Reformed Theological Seminary chancellor emeritus Ric Cannada has been watching Barker since Cannada first entered the ministry.

“I think it’s his example,” Cannada said. “You can teach evangelism, but it’s largely caught. When you’re around Frank and seeing how he does it naturally and easily—it’s catching.”

Involved in Women’s Ministry? Add This to Your Discipleship Tool Kit.

We need one another. Yet we don’t always know how to develop deep relationships to help us grow in the Christian life. Younger believers benefit from the guidance and wisdom of more mature saints as their faith deepens. But too often, potential mentors lack clarity and training on how to engage in discipling those they can influence.

We need one another. Yet we don’t always know how to develop deep relationships to help us grow in the Christian life. Younger believers benefit from the guidance and wisdom of more mature saints as their faith deepens. But too often, potential mentors lack clarity and training on how to engage in discipling those they can influence.

Whether you’re longing to find a spiritual mentor or hoping to serve as a guide for someone else, we have a FREE resource to encourage and equip you. In Growing Together: Taking Mentoring Beyond Small Talk and Prayer Requests, Melissa Kruger, TGC’s vice president of discipleship programming, offers encouraging lessons to guide conversations that promote spiritual growth in both the mentee and mentor.