Leon Lamb Morris (1914–2006) stood out in his generation as one of the great evangelical scholars. He wrote 50 books and traveled extensively, speaking all around the world. His book The Apostolic Preaching of the Cross, which has sold more than 50,000 copies, was his signature achievement. He wrote often about the cross, and his more popular treatments were also well-received. Morris stubbornly attended to the biblical text and closely sifted what it said, showing that penal substitution and the satisfaction of God’s wrath could not be expunged from our theological vocabulary. His massive NICNT commentary on the Gospel of John should probably be mentioned second in terms of its influence and scholarship. The effect of his writings is staggering. He wrote two commentaries (Tyndale and NICNT) on the Thessalonian epistles, and they sold more than 250,000 copies. His Tyndale commentary on 1 Corinthians, which appeared in two editions, also sold more than 250,000 copies.

Morris’s work in The New Testament and Jewish Lectionaries refuted the notion that the Gospels were patterned after lectionaries. As a young student I read much of his work. The first scholarly commentary I read on Revelation was by Morris, and I also read his helpful little book on apocalyptic literature. His fascinating book on church government is vintage Morris: fair, insightful, balanced. I was also instructed by Morris’s volume on Scripture, I Believe in Revelation.

Morris the Man

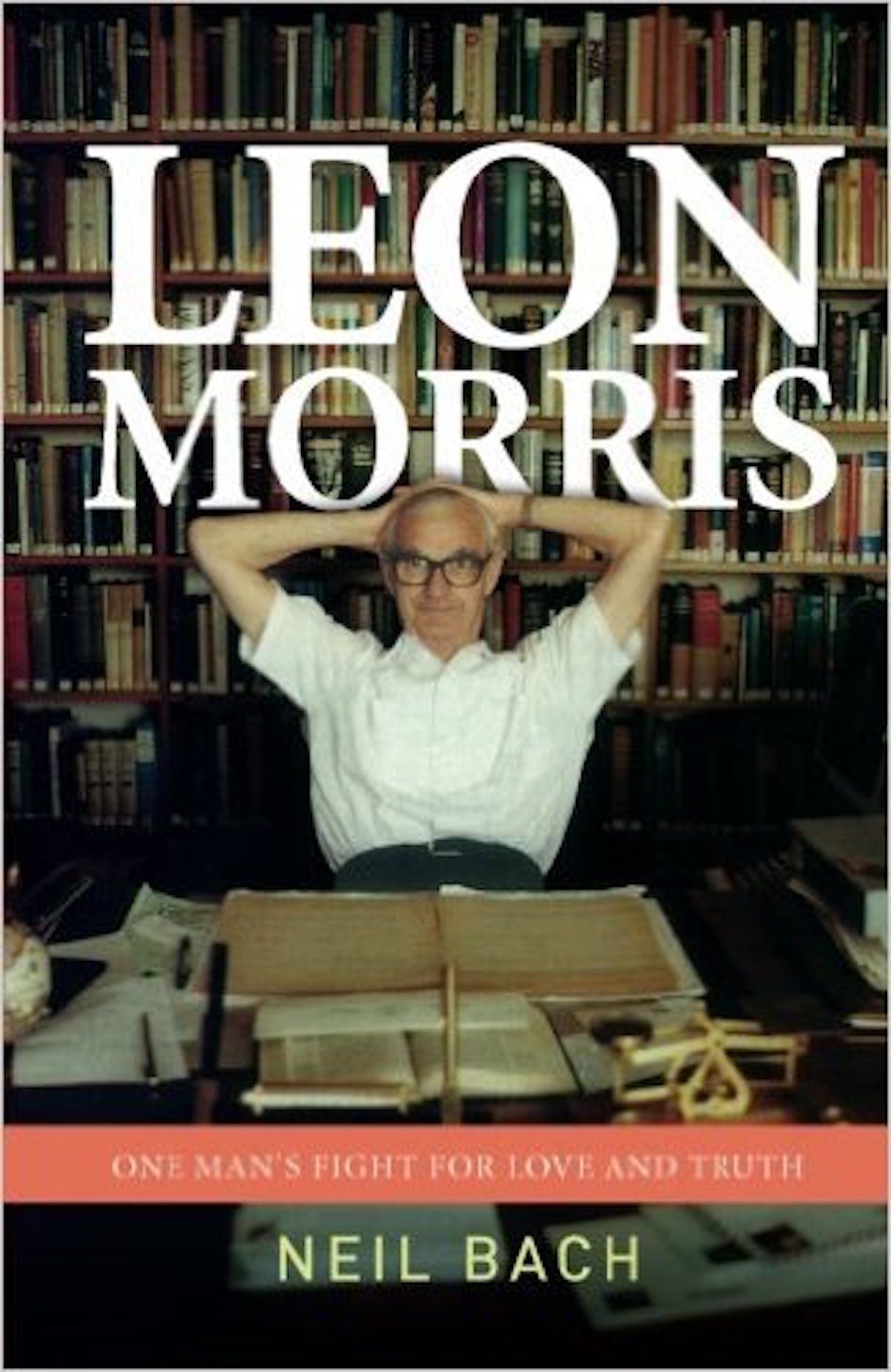

Many of us know about Morris’s writings, but we know less about Morris the man. Neil Bach—an Anglican minister who chairs the Leon and Mildren Morris Foundation—has now written a biography, Leon Morris: One Man’s Fight For Love And Truth, that captures Morris’s life from his humble beginnings in Lithgow (in the state of New South Wales) to his final years in Australia, where he suffered from dementia.

Morris was converted in his first year of study at the University of Sydney, and his intellectual gifts quickly manifested themselves. He married Mildred Dann in 1941, and they were married for 62 years until her death in 2003. They never had children. Morris served for a short period at Tyndale House (1961–64), but he also devoted many years to being principal of Ridley College in Melbourne.

Leon Morris: One Man's Fight for Love and Truth

Neil Bach

Bach rightly devotes most of the book to Morris’s scholarly career—to his writing, speaking, and interaction with other scholars. Perhaps a few reflections from the biography will be of some interest. Morris was clearly a humble and teachable person. He was self-effacing and not self-promoting, which is a good word in this day when the temptation to promote ourselves is part of the air we breathe. At the same time, he had an impish sense of humor others enjoyed. He had enormous energy and discipline; hence he could serve as a college principal and also write a tremendous amount. He ran meetings with efficiency so that no time was wasted. Bach recounts one incident where Morris stood up and ended a meeting on time while someone was declaiming on this or that. The person cut off was quite astonished!

Intensely Private, Tenaciously Biblical

Bach hasn’t written a biography that introduces us to the interior life of Morris or his wife. Apparently they were both quite introverted, so there’s probably no access to this dimension of their lives. We don’t learn whether not having children was a struggle for Morris or his wife. There are no windows into Morris’s heart. It seems he kept the door shut on his private life and thoughts.

What was it like to work with Morris day in and day out? It seems it was pleasant, though when Alfred Stanway came to help him with administration at Ridley in 1971, Stanway discovered Morris couldn’t delegate responsibilities, and they clashed. Clearly, Morris was a godly man—humble, caring, unselfish. On the other hand, we’re all flawed until the day of redemption, and it’s a bit difficult from this biography to discern his areas of weakness.

One of the remarkable features of his life was that Morris continued to write until dementia overtook him. Some might be surprised to learn he was an advocate for women serving in all ministry positions. Morris’s ability to get along with people manifests itself in the welcome he received at both Fuller Theological Seminary and Trinity Evangelical Divinity School. At the end of his life he wrote commentaries on Matthew and Romans, as well as a New Testament theology.

Morris’s lucid and clear expositions continue to inspire students today. And as Bach shows, Morris was committed to Jesus Christ, to the Scriptures, and to teaching, preaching, and writing. His legacy lives on. I’m thankful to Neil Bach for his biography of a man who played such a vital role in evangelical scholarship in the 20th century.