Kelly Chibale’s life sounds almost exaggerated, like it was based on a true story. An African child born into desperate poverty rises through education, talent, and hard work to become a post-doctoral researcher under one of the best chemists in the world.

And then, in the mid-1990s, he faced a choice: Go back to England to finish his fellowship or take a three-year position at the University of Cape Town (UCT).

Pros: The England opportunity offered more money, more prestige, more opportunity for research (which Chibale loved), and more possibilities to collaborate with the top minds in science. Cons: Cape Town was a temporary appointment, with weaker research facilities and limited funding, in a country that had just come out of apartheid. (Chibale is a black African.)

“Cape Town is a teaching college—there is no research there,” one pharmaceutical executive told him. “You’re going to waste your time.” Chibale thought maybe he was right. “But I could sense God’s calling. You couldn’t talk me out of it.”

It’s been nearly 23 years, and, if anything, Chibale’s life sounds even more like a Hollywood script today. He raised funding for—and built—a research center, gathered a team, and discovered not one, but two possible cures for malaria. (The disease is one of the leading causes of death in African children younger than 5 years old.)

From the Financial Times to Fortune magazine to science journals, Chibale has been featured and interviewed and photographed. “Kelly Chibale: An advocate of innovation,” read one headline from 2012. “UCT Scientist Kelly Chibale: From poverty to a global leader,” reported another in 2018. And from March: “Kelly Chibale: Leading the way in African drug discovery.”

But Chibale doesn’t take any credit.

“What I’ve done would not be possible without God,” Chibale, who is an elder in his church, told TGC. “I put [my success] down to the prayers of my wife and my church.”

That’s no small thing—his wife, Bertha, has spent the last 29 years praying for Chibale. Their church has been praying, too, especially during the critical start-up months.

“It’s important for me that people know I am a disciple of Jesus,” Chibale said. “Science is what I’m called to do, but it doesn’t define me. It’s my relationship with the Creator that’s the most important thing. The rest is just noise.”

Schooling in the Slums

“I grew up in townships—you might call them slums,” Chibale said. The village where he was born was so remote that when the bus dropped him off at the literal end of the road, he still had to walk about eight to 10 hours. Even when he moved to a larger town, there was no infrastructure for running water or sewage, no room for beds (almost everyone slept on the floor), no money for shoes.

Chibale’s father died when he was 2 months old, and his mother bounced from home to home, sometimes keeping Chibale and his brother with her, sometimes forced to farm them out to someone else. He remembers sleeping on the floor at his uncle’s house, sleeping next to distant cousins he didn’t know, sleeping in a ditch one night when his abusive stepfather wouldn’t let him into the house.

The frequent moves meant he was often switching schools in an educational system barely older than Chibale himself. When Zambia gained independence from Britain in 1964—the same year Chibale was born—there were only 100 university graduates in the entire country. (Since Zambia didn’t have a college, all of them were educated somewhere else.)

Zambian government officials got to work providing free primary education to both boys and girls, abolishing racial segregation, and creating a university. But it was slow going with few resources. And when Chibale failed the exam that would pass him on to eighth grade, so did about 80 percent of other Zambian boys that year.

To this day, there’s nothing that makes more sense to me than organic chemistry.

“My uncle couldn’t keep me, and my mother didn’t have anywhere to stay, so she sent me back to the original village to live with my grandmother and repeat seventh grade,” Chibale said. “It was then I woke up, because I realized if I didn’t work hard, I didn’t have a future.”

He passed the second time around, then moved to a rural town in northern Zambia for high school. His holidays were spent in different townships, which all had the same problems—no electricity, no running water inside the house, and overcrowding. One was “exceptionally terrible.”

“It was more of an informal settlement,” Chibale said. “People built their houses with mud or a plastic sheet or stuff like that. There was no running water or electricity or flush toilets. You bathe at night when it’s dark so people can’t see you.”

He studied all the time—during the day at a public library, at night using a little kerosene lamp that blew out every time he turned a page. Most of the time he studied chemistry.

“When I was in high school, I was fascinated by doing chemistry experiments, when you mix chemicals and see color changes,” he said. “When I got to university, I was doing more advanced chemistry but also learning the various subdisciplines.”

His favorite was organic chemistry. “I was drawn to it,” he said. “It felt like a calling. To this day, there’s nothing that makes more sense to me than organic chemistry.”

From Witness to Baptist

Chibale’s mom was a Jehovah’s Witness, which was a growing movement in Zambia in the ’60s. Early missionary work was sometimes opposed as being seditious, but conversions took off around 1950, when “attention was . . . given to the thousands of Europeans who had moved there in connection with copper-mining operations.” Today, Zambia has a higher Witness-to-population ratio (1 to 83) than the United States (1 to 265). (And Witnesses are still accused of being antigovernment.)

Chibale grew up going to the local Kingdom Hall, but by the time he got to the University of Zambia, he was more interested in alcohol and parties.

“This friend of mine, he was—we were—alcoholics,” Chibale said. “But then this guy came to faith. He was born again at the University of Zambia, because somebody from the University Christian Fellowship witnessed to him.”

The friend started attending a Baptist church, and “relentlessly” invited Chibale to go with him.

“Eventually I agreed to go,” Chibale said. Between the university ministry, the church, and his friend, Chibale was cornered. “That’s how I came to faith. It changed my life.”

Chibale watched other students graduate from the University of Zambia and head overseas on scholarships for further studies. He wanted to do that, too. But when one application after another was rejected, he took a job in north Zambia with a company that makes explosives for the mining industry.

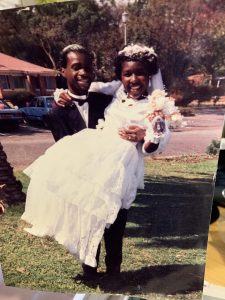

While there, he started attending a Baptist church, then attending more often when a girl in the choir caught his eye. Twenty months later, he’d been offered a scholarship to study chemistry at Cambridge University in England. A year after that, he married the girl.

“The Bible says the vision waits for the appointed time,” Chibale said, referencing Habakkuk 2:3. “There are no delays with God.”

Studying Overseas

The scholarship Chibale got was a Cambridge Livingstone Trust scholarship, named for Scottish physician and missionary David Livingstone and reserved for scholars from the countries he visited.

The first year was probationary, to see if scholarship winners could keep up. At first, Chibale didn’t think he could.

“My life was in the lab,” he said. He worked seven days a week, breaking only for church. “I used to cry because I couldn’t even repeat experiments,” much less create his own. He was behind the other students, who had gone to better schools.

But he was also driven, and he was good at the work. He caught up to his peers, passed his probationary year, and finished his PhD in three years.

By now he was deep into synthetic organic chemistry.

“Imagine you go to a forest and chop down a tree and you find its roots have molecules that can kill cancer cells,” he said. “Organic chemists will determine the chemical structure of that molecule responsible for the anticancer activity and separate it from the inactive ones around it.”

Now imagine you need to supply great quantities of this molecule as medicine to thousands of cancer patients. A synthetic organic chemist will take the molecule “that God has put out in nature” and work backward, simplifying it into smaller bits until they can see how to work forward, building it from scratch.

Chibale’s first postdoctoral residence was at the University of Liverpool, developing methods for making molecules. His second was at Scripps Research Institute in California, building molecules.

Praying Wife

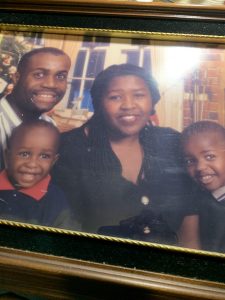

Bertha gave birth to their first son while in Cambridge, the second in Liverpool, and the third in Cape Town, South Africa.

Switching cultures every few years while raising three young boys was “quite hard,” she said. “It was a big adjustment for me.” She was alone a lot—especially during a five-week stretch when Chibale had to leave for California but she had to stay in Manchester with their second baby, who had a bone infection.

“God was amazing,” she said. “He gave me supernatural strength. Somehow I took everything in stride.”

She knew Chibale was called to chemistry, and she felt called to him.

“I’m not complaining when he’s away again, because this is the life God has called me to, and he’s empowered me to be the wife of this guy,” she said. “My friends say, ‘How do you allow it?’ But for me it was never an issue.”

She grew her faith by trusting God for little things, like money or patience, and “it seemed like God was answering every prayer.”

He was answering the bigger prayers too. At Scripps, Chibale got to work with famed synthetic organic chemist K. C. Nicolaou. His stipend was so generous they could afford two cars. And their son was healed from the bone infection. (“The doctors told me our son would have a limp and not be sporty,” she said. “I was like, ‘Okay, I hear you, doctor, but God is able too.’ And he’s been the most sporty of all our children.”)

The Chibales were on a trajectory that angled steeply up.

Until it dropped steeply down.

University of Cape Town

“My decision to come here was not easy,” Chibale said from his office at the University of Cape Town, walls lined precisely with diplomas and awards. “I was in a fellowship that was supposed to take me back to England.”

But he wanted to study his own thing. And he missed Africa. And, most of all, he felt a calling.

“I remember my adviser saying, ‘Why do you want to go back to Africa?’” Chibale said. “Deep down, it was like a missionary going to some war-torn area.” You can’t exactly explain why you’re going, but no one can talk you out of it.

In less than a year, Chibale’s temporary job was converted into a permanent one. But some of his colleagues—who were also on temporary contracts—didn’t like that.

One filed a lawsuit, accusing the university of promoting Chibale because he was black. It had been only a decade since apartheid had been banned, and the government was leaning on companies to use affirmative action to hire and promote black South Africans. This case was doomed from the start, because while Chibale is black, he isn’t South African.

Still, “it was deeply offensive to me, and I was deeply hurt,” Chibale said. “He trivialized all of my hard work and sacrifices. . . . It hit me really badly.”

Chibale had to deal with lawyers. He had to appear in court, where he felt like a criminal. He wondered if the media would get a hold of the story and tell everyone that he wasn’t really qualified for his job. He overheard hurtful comments in the staff break room and quit showing up there. He didn’t sleep. He cried a lot.

But “when you have challenges, it pushes you into God,” Bertha said. “You learn to trust him.”

Chibale did, leaning into God one day after another. “Even when we doubt him, he stays faithful and doesn’t treat us as our sins deserve,” he said.

Eventually, the university won the lawsuit. Chibale kept his promotion. The media didn’t write about it. And the drama drove Chibale even deeper into his work.

“If somebody thinks you can’t do something, when you find an opportunity, just educate them,” he said.

H3D

About six or seven years after the lawsuit, Chibale was itching to start his own research center focusing on the discovery of new medicines.

“I had three reasons,” he said. “It looks like I was being rational, but I was never rational. I can list these with the benefit of hindsight.”

- Africa is “the most disease-prone continent,” World Bank Group’s Health in Africa Initiative head Khama Rogo said in 2017. The continent carries 25 percent of the world’s disease burden but spends less than 1 percent of the world’s financial expenditures on health.

- Most of African’s health care has been provided by foreign countries (often missionaries), due to poverty and lack of education. “Africa has benefited immensely from health innovations that have come from the developed North,” Chibale said. “The Bible says it is in giving that you receive. It’s time for us to contribute and to debunk the myth that Africa is not, and cannot be, a source of health innovation.”

- In the United Kingdom and United States, Chibale saw entrepreneurship science—developments that created jobs. “We can’t wait for the government to give handouts or create jobs,” he said. “The government should provide the environment where entrepreneurs can flourish.”

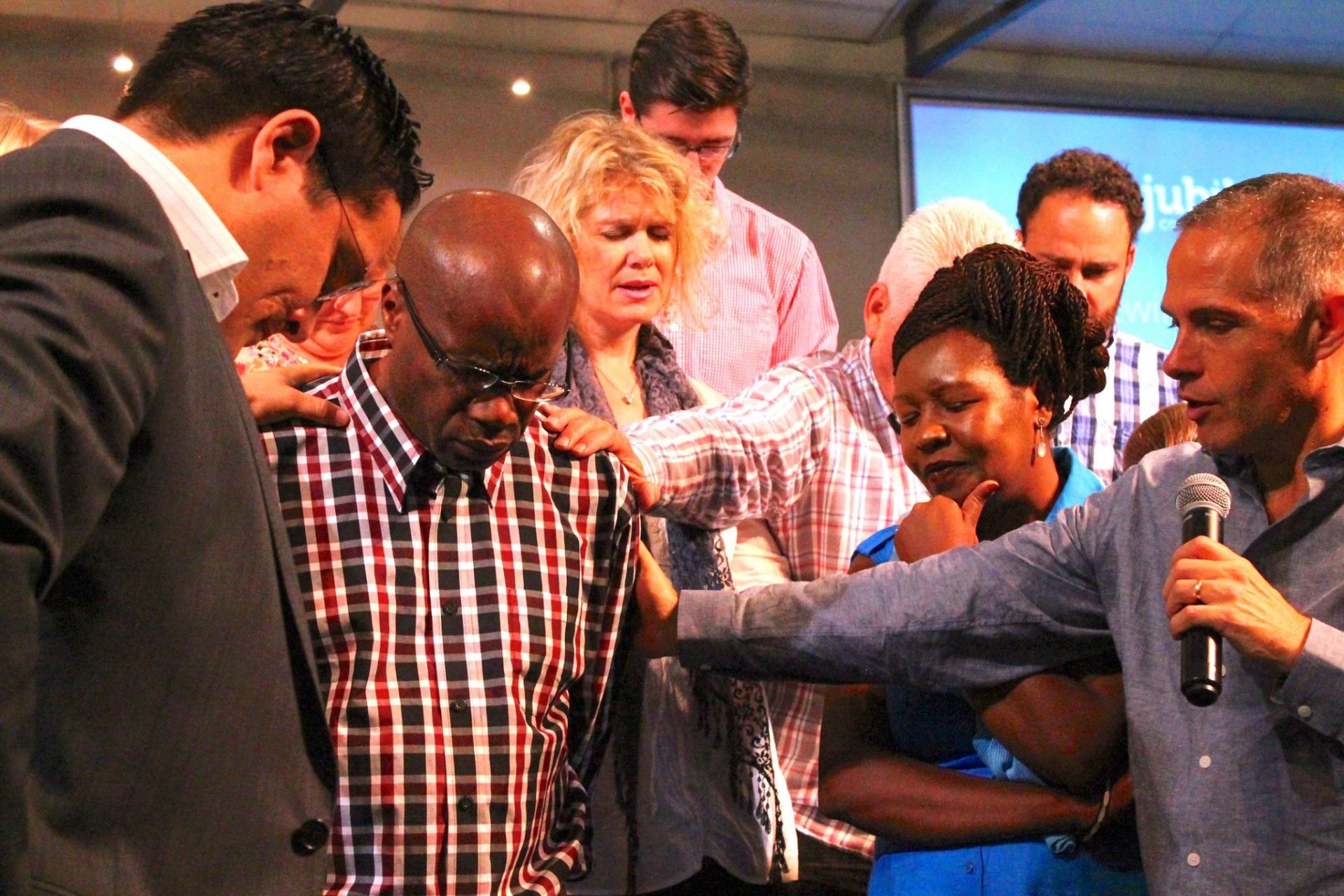

“God brought me to the point where I had a vision of creating this center that would contribute to solving these challenges,” Chibale said. At the same time, he and Bertha began attending Jubilee Community Church, a multiethnic, Reformed, evangelical, charismatic congregation with Baptist roots that go back to Charles Spurgeon.

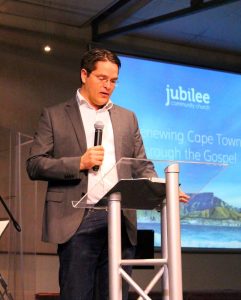

“Around that time period, I was realizing God wants Christians involved in renewing culture, and I was reading [Tim Keller and Redeemer’s Center for Faith and Work] and reflecting on that,” pastor Stephen van Rhyn said. “We developed a relationship with Kelly and Bertha, and he really helped me posture even better. He gave me a meaningful paradigm for that.”

“Stephen was the one person I actually confided in and shared the vision of what I wanted to do,” Chibale said. “He gave me the message through his preaching that you don’t need to be called to the ministry to really work for Jesus. You can be in the marketplace and still impact people for the gospel, because we all have different callings. . . . I got a lot of encouragement from knowing we can be ministers of the gospel through the work we do. Christian life is not just on Sunday. It’s every day.”

Chibale told van Rhyn that he wanted to start a center that would research and develop drugs. He told him about wanting to cure Africa’s diseases, to contribute to human health care, to provide jobs. He told him he needed $5 million just to get started with the necessary infrastructure, enabling technologies, and skilled scientists.

“That really resonated with me,” van Rhyn said. “I saw him trying to step out in faith and believe God. But he needed help.”

So van Rhyn brought it up at the congregation’s monthly prayer meeting.

“Everybody gave a big gasp,” Bertha said. “That’s a lot of money.” (Convert it to South African rand and the amount is “even scarier,” Chibale said.)

But van Rhyn had been talking to Jubilee about trusting God, and about working not just with those who were down-and-out but also affecting culture from upstream.

The church already ran a low-cost health clinic, offered free HIV testing, and operated a pregnancy center. It wasn’t hard to get the congregation to see why medical research mattered.

“In a sense, this was just a helpful illustration of something we’d already communicated to the congregation,” van Rhyn said.

So they prayed.

Three years later, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation gave the University of Cape Town a grant of $5 million—with matching funds from the South African government—to initiate work on the discovery of new drugs for malaria and tuberculosis. (The Gates Foundation today remains one of the center’s biggest funders.) Before direct funding from the Gates Foundation, the Swiss-based Medicines for Malaria Venture (MMV) also kicked in, followed by global pharmaceutical giant Novartis.

In 2010, Chibale founded the Drug Discovery and Development Center (H3D), Africa’s first—and so far, only—drug-research facility of its kind. H3D focuses on “harnessing modern pharmaceutical industry skills and expertise in the drug discovery value chain, while also working to train a critical mass of African scientists with the capabilities of discovering modern medicines,” Chibale said.

Malaria

The malaria parasite is as old as sin; it’s been found in skulls thousands of years old, and mosquitos even older.

After entering a human through the bite of an infected female mosquito, the parasite travels to the liver, grows to maturity, then fans out through the bloodstream, all the while reproducing itself. Patients get a fever and chills along with nausea, fatigue, and headaches. Left untreated, patients can experience brain swelling, anemia, organ failure, or death.

Malaria thrives in warm, moist climates where mosquitos can live all year long, and in children whose immune systems aren’t yet developed enough to fight it off. The most vulnerable population, then, is children in sub-Saharan Africa: In 2017, nearly 247,000 died from malaria, about one every two minutes.

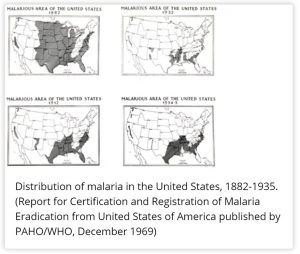

Scientists identified the malaria parasite in the late 1800s. By 1951, the United States had eradicated it by draining standing water and spraying the insecticide DDT all over lawns and homes. Buoyed by that success, in 1955 the World Health Organization (WHO) proposed spraying insecticide and handing out antimalarial drug treatments to eradicate it worldwide.

The plan worked in more temperate climates with stable populations. But the parasite grew resistant to the drugs, and wars meant people moved around—and anyway, the WHO hadn’t included sub-Saharan Africa in its experiment.

The WHO tried again in 1998 with the Roll Back Malaria campaign, which convinced some African governments to switch to more effective antimalarial medicine, pass out mosquito bed nets, and connect hundreds of agencies all working on the problem. It helped, but not enough.

Because no matter how quickly you invent medicine, malaria is just as quick.

Resistance

The malaria parasite is just one cell, and flexible. So far, it’s developed workarounds for every medicine scientists throw at it—including chloroquine, sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine, mefloquine, and artemisinin. (For example, chloroquine-resistant malaria parasites learned to spit out the chloroquine drug before it builds up enough to become toxic.)

So Chibale wasn’t looking for the end-all stop to the disease, but for another arrow in the medical industry’s quiver.

His team, in partnership with MMV, knew most malaria patients are poor and rural, so their medication had to be inexpensive, taken orally instead of injected, and delivered in one dose. And it had to be safe enough that it could be taken by children.

They asked an Australian team with better technology to sift through 35,000 molecules to find those that could kill the malaria parasite. Then Chibale’s team tested the molecules’ effectiveness, exposure, and safety to find “an optimized molecule with the desired properties.”

For most potential medications, this stage is the last. Scientists call the jump from animal to human testing the “valley of death,” because most drugs aren’t effective or safe enough to make it.

But Chibale’s compound—called MMV048—proved safe for humans. It moved through Phase 1 (testing on healthy humans) onto Phase 2 (testing on malaria patients). So far, it seems to kill malaria in all stages of its life cycle. It works against the strains of malaria already resistant to other drugs. And it may be able to block the transmission of malaria through mosquitos.

In 2010, Chibale founded . . . Africa’s first—and so far, only—drug research facility of its kind.

That a six-person research team in a brand-new center was able to lead an international effort to discover a molecule in 18 months and move a drug to clinical trials in six years is a “miracle,” Chibale said.

“The industry norm is to spend millions of dollars and use massive teams of scientists,” he said. “If I told anybody I was doing this, they’d say, ‘You must be joking. Do you even know what it takes to discover a drug?’”

But “I knew what God had called me to do,” he said. “God took me one step at a time.”

Source of Science

Today, H3D has grown from six postdoctoral students to 60 experienced scientists. They’ve pulled in millions of dollars in funding. They’ve moved into state-of-the-art facilities. And they’ve discovered—and rejected for safety concerns—a second antimalarial drug.

Last year, Chibale was named to Fortune’s list of the world’s 50 greatest leaders. (He was #45, a few spots behind Tim Keller at #41.)

And he became an elder at Jubilee.

“It’s important to understand that not just pastors are called to disciple people,” Chibale said. “It’s all of us. I think by the grace of God, the prominence I have does allow people to see work as a calling. We’re all taking care of different needs.”

Faith and work “is not just theoretical,” van Rhyn said. “It’s practical and tangible. . . . Kelly embodies what can happen when you put five loaves and two fishes in the hands of God—how he can multiply that. And Bertha has been an awesome example to us in terms of believing in prayer.”

In Chibale’s field, commitment to Christianity can be unusual. “People don’t think scientists like me can have faith,” he said. “But the deeper you go into science, the more amazed you stand at your Creator.”

He tries to thank God as often and as publicly as he can.

“What I’ve done would not be possible without God,” he said. “I put it down to the prayers of my wife and church. . . . Faith is not a weakness in science, because God is the source.”

Are You a Frustrated, Weary Pastor?

Being a pastor is hard. Whether it’s relational difficulties in the congregation, growing opposition toward the church as an institution, or just the struggle to continue in ministry with joy and faithfulness, the pressure on leaders can be truly overwhelming. It’s no surprise pastors are burned out, tempted to give up, or thinking they’re going crazy.

Being a pastor is hard. Whether it’s relational difficulties in the congregation, growing opposition toward the church as an institution, or just the struggle to continue in ministry with joy and faithfulness, the pressure on leaders can be truly overwhelming. It’s no surprise pastors are burned out, tempted to give up, or thinking they’re going crazy.

In ‘You’re Not Crazy: Gospel Sanity for Weary Churches,’ seasoned pastors Ray Ortlund and Sam Allberry help weary leaders renew their love for ministry by equipping them to build a gospel-centered culture into every aspect of their churches.

We’re delighted to offer this ebook to you for FREE today. Click on this link to get instant access to a resource that will help you cultivate a healthier gospel culture in your church and in yourself.