When Vinicius Pimentel was 12 years old, his parents got divorced, and he started going to church by himself in Americana, São Paulo.

He didn’t go to the Nazarene church he grew up in, but to a neo-Pentecostal church. At first, there “was not a lot of good theology but not a lot of bad theology—just love for Jesus and evangelism and, of course, the gifts of the Spirit.”

But over the 12 years he spent there, the teaching moved steadily into “more health-and-wealth theology and coaching to be the best version of yourself,” Pimentel said. As a leader, he worked hard to attract more people to the faith, even planning a disco party at the church.

“We tried to attract people with any possible strategy, to convince them to be converted,” he said.

And then he broke his leg. He calls it his “God wrestling with Jacob” moment.

“I had more time to be at home on the internet,” he said. While browsing a Christian YouTube channel, he clicked one that was at the top because it was trending in the United States—evangelist Paul Washer’s “shocking message.”

“It was a shock for me,” Pimentel said. “I remember crying that whole night, and a big hunger started in my heart. I wanted to know more about the Word.”

He clicked on more videos, watching dozens of John Piper videos that Desiring God released for free. “I didn’t know the distinctives of Reformed theology, but I knew I wanted more of the gospel I was hearing.”

In Brazil, Pimentel’s story is typical—he hears other people telling their version of it “a lot.” Because he isn’t the only one. More than 2.5 million have watched the version of Washer’s “shocking message” with Pimentel’s added Portuguese subtitles. Another million have seen it dubbed over in Portuguese.

Some dig in farther. Reformed pastor Renato Vargens’s blog has received more than 21 million pageviews since he started in 2010. Pimentel started a website called Voltemos Ao Evangelho (Let’s Get Back to the Gospel) where he’s posted thousands of Reformed sermons—in Portuguese or with subtitles—since 2008. More than 750,000 follow the blog, while 133,000 subscribe to the YouTube channel.

Last year, TGC launched a Brazilian Council and website. This February, when TGC held its first conferences, about 4,000 came to hear Piper speak in São Paulo. The next week, he spoke to another 12,000 at a Reformed-leaning conference in Campina Grande.

“Ten years ago, I didn’t think I’d ever see [this enthusiasm for the gospel],” said Southern Baptist Convention (SBC) missionary W. Mark Johnson, who serves as theological educational strategist for the International Mission Board in Brazil. “It’s the best moment I’ve seen in my 26 years here.”

“I’m not just hopeful for a revival,” said Yago Martins, who found his way from prosperity gospel to Reformed theology through Piper videos. Today his YouTube channel on Reformed theology has almost 400,000 followers. “It’s already happened. It’s growing in an unstoppable and inescapable way.”

For John Calvin, it would be further evidence of God’s sovereignty. Because when he sent the first Calvinist missionaries to Brazil in 1556, it was an unmitigated disaster.

Calvin’s Only Missionaries

More than 460 years ago, a band of several dozen Calvinists—including two pastors—left Geneva to join a struggling French colony in Brazil. They were the first foreign missionaries dispatched by the new Protestant church, and their job, in part, was to “indoctrinate the savage and bring them to the knowledge of their salvation.”

But when the leader of their colony converted back to Roman Catholicism, he “strangled three Calvinists and threw them into the sea,” religious freedom expert Thomas Schirrmacher wrote. By 1560, all had fled—most back to Europe—or were killed.

The mission was “not a grand and glorious success,” Johnson said. (Schirrmacher calls it a “tragic failure.”) But it was the first wave on the beach. Four of the lay members wrote the country’s first Reformed confession 12 hours before they were hanged.

The second wave came in the 1600s, when the Dutch invaded northern Brazil and brought Reformed pastors with them. Within 25 years, the Dutch were ousted by the Portuguese, but they left their mark—the former Dutch city of Recife is now “a conservative Reformed stronghold,” Johnson said.

The third wave landed in the 1860s, led by a Presbyterian missionary couple who both died within eight years—she in childbirth, he of yellow fever. But in that time, Ashbel Green Simonton organized a church and printed a monthly publication articulating an alternative to Catholicism. By 2011, Simonton’s Presbyterian Church of Brazil denomination had more than a million members.

The Baptists arrived in 1881, and within 60 years, had more than 68,000 Brazilian members in almost 780 Southern Baptist churches. But none of them was explicitly Reformed in its theological convictions.

The Baptists arrived in 1881, and within 60 years, had more than 68,000 Brazilian members in almost 780 Southern Baptist churches. But none of them was explicitly Reformed in its theological convictions.

“Those spiritual forefathers are what you’d call generically evangelical. Positively, they chose for their first Baptist Confession in Brazil the New Hampshire Confession, which is ‘Reformedish,’ but not strongly Reformed,” Johnson said. “Baptists grew based on revivalism. They were strong on evangelism and church planting, but their theology, although it was generally conservative, was not detailed and robust. They didn’t get deep into the theological weeds.”

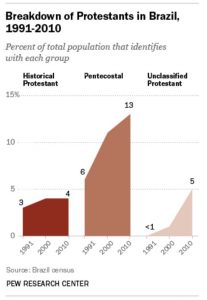

In the 1960s, both the Presbyterian and Baptist efforts in Brazil were dwarfed by the Pentecostalism that roared across Latin America. By 2014, eight in 10 Brazilian Protestants were Pentecostal. Most had witnessed an exorcism (56 percent), seen a divine healing (72 percent) or witnessed speaking in tongues and prophesying at church (91 percent).

“When I got to Brazil [in 1993], I thought the future was Pentecostalism, which was increasingly moving in the direction of prosperity theology,” Johnson said. By 2014, 56 percent of Protestants and 52 percent of Catholics said that “God will grant wealth and good health to believers who have enough faith.”

“It’s embarrassing to say I was faithless—I was hopeless,” Johnson said. “But that’s what it looked like 20 years ago.”

Martyn Lloyd-Jones’s Missionary

Rick Denham is a third-generation Baptist missionary. His father’s parents worked in China, sailing up and down the major rivers delivering the gospel to hard-to-access areas. After being kicked out by Communists, they headed to another large river that could take them to hard-to-reach people groups. Rick’s father joined them on the Amazon in 1952 with his new wife, who sold her grand piano to pay for a boat.

There, Denham’s father met a missionary sent from a British church pastored by Martyn Lloyd-Jones.

Bill Barkley “brought the Banner of Truth magazines and introduced them to my dad,” Denham said. “He introduced him to Lloyd-Jones and Spurgeon and Calvin. My dad caught on fire for that theology.”

Barkley and Denham both moved to São Paulo and started publishing Christian literature. Between the two of them, they translated and published sermons and written works by the Reformers and the Puritans, by Calvin and Spurgeon and Lloyd-Jones. Eventually, they’d publish translations of Piper, R. C. Sproul, and John MacArthur.

At first, it was slow going. Barkley’s Selected Evangelical Publications and Denham’s Fiel—or “faithful”—Publishing could only release a book or two a year. But after a while, those added up. The men would load up books on a bus and drive around, selling them at reduced prices.

“Hundreds of people came for very good literature,” said popular Brazilian pastor and speaker Augustus Nicodemus Lopes, who first learned of the doctrines of grace from a book by Charles Spurgeon. Lopes, who spoke at the 2015 TGC national conference, leads the oversight committee for the 10 Presbyterian seminaries in Brazil.

When Lopes was in seminary, “I read Calvin in Spanish because it was not translated into Portuguese yet,” he said. “We didn’t have the Institutes in Portuguese. I studied Louis Berkhof’s systematic theology in Spanish. Today you can find anything in Portuguese. This work of the publishing houses is fundamental to what is happening here in Brazil.”

This work of the publishing houses is fundamental to what is happening here in Brazil.

Some Western Reformed personalities fit better with the culture. “The reason Martyn Lloyd-Jones was so attractive, especially to Pentecostals, is that he believed you do have an experience with the Holy Spirit after conversion,” Lopes said. “He’s not a charismatic at all, but he follows a more of a Puritan tradition, which is more wired to experiential religion. . . . That’s a powerful combination for the church in Brazil.”

Later, Piper and Washer would explode in popularity. Both combine biblical expository preaching with strong emotions and near-constant hand movement. “Their kind of preaching is like our kind of preaching,” Martins said.

Meanwhile, in the late 1980s, Fiel was adding a conference—just a “mom and pop” event, Johnson remembers. It drew somewhere between 70 and 80 pastors.

But as more books were published, more people grew familiar with Reformed names. When Fiel brought in high-profile authors—Piper, MacArthur, Michael Horton, Joel Beeke—in the mid-1990s, attendance jumped to around 600 or 700.

Still, in a country of around 160 million, the numbers weren’t huge.

Reformation Via Social Media

Rafael Bello grew up in a morally liberal Baptist church—his mother and grandmother were converted through missionaries sent from The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary back in 1910.

While Bello was in college, he was “working in a small church library, cataloging stuff,” he said. “And I just started reading some of it—books by R. C. Sproul or DVDs of John Piper.” (The titles were from Fiel Publishing.)

“I started getting more involved with that deeper theology,” Bello said. “And I knew English. . . . I talked to my friends—‘What if we did a really cool website where we posted translated articles and videos?’”

They started with Portuguese subtitles on YouTube videos.

At first, “it took a long time to translate a one-hour sermon,” he said. “I got really proficient at it. I was doing five-minute videos—you know, those short Desiring God videos—once a week or so. A lot of people liked it.”

Bello and his friends started translating “a bunch of TGC articles” and content from “Russell Moore’s website.”

“People started to follow us,” Bello said. Thousands of people.

One of them was Martins, who then started his own Reformed YouTube channel. To him, the gospel on YouTube seems like “treasure in jars of clay” (2 Cor. 4:7).

It also seems like history repeating.

“A little while before Martin Luther started the Reformation, the printing press was invented by [Johannes] Gutenberg,” Lopes said. “If there had not been a printing press, the Reformation would not have come out of the doors of Wittenberg. . . . Social media is doing something similar today.”

From Catholic to Pentecostal to Reformed

“Pentecostals have done a good job of preaching [about salvation],” Lopes said. Thousands of people are “getting converted, and then they go to an Assemblies of God Church.”

But once there, “some of them hunger for the Word of God,” he said. “They want more biblical teaching, and they don’t always hear it from their pastors. So they go to YouTube and watch John Piper and Paul Washer.”

Hooked by the expository preaching, they keep watching and listening to the thousands of translated and original videos and articles on Reformed theology.

“The next step is they become Reformed,” Lopes said. “This is happening everywhere.”

For example, this month he preached in a small church near his town. In the crowd—which began to gather an hour and a half before his talk was scheduled—sat a Pentecostal preacher and his entire congregation.

“I have seen this so many times—people coming from the Pentecostal church,” Lopes said.

It’s a twist no one saw coming: The growth of the charismatic movement in Brazil has become a pathway for thousands to find Reformed theology.

Reformacostals

“I like to preach to them,” Lopes said of Pentecostals. “They applaud, they shout ‘hallelujah,’ they raise their hands. It’s encouraging.”

It’s also out of place in most orderly Reformed congregations.

“People who have been in this church forever see it as ‘our church,’” he said. “’Who are these new people with tattoos and piercings and dyed hair? They’re noisy and they shout hallelujah and clap. Who are these people?’”

So far, the reception has been good, he said. But “this is going to require a change in the way people who have been here see the church.”

It can be awkward and uncomfortable on both sides.

“Suppose the Pentecostal preacher and his congregation who came to my preaching decide they can’t stay in the Assemblies of God,” Lopes said. “So they come to my Presbyterian church, where they’re going to find it weird. We don’t shout or raise our hands. Our service is a little bit formal. They won’t feel at home.”

A congregation or a pastor or an individual in this situation can’t go forward and can’t go back, he said. “The people who are half-Pentecostal and half-Reformed are a little bit homeless at the moment.”

Some start new churches. Others stay in their charismatic denomination but go to Presbyterian churches and conferences as often as they can to fill up on biblical preaching.

“For a lot of them this is an existential crisis—they don’t know what to do,” Lopes said.

Another problem is the training. “There are a lot of [Pentecostal] pastors who never went to formal training,” Lopes said. “So if they become Presbyterian, they have to go to a Presbyterian seminary and fall under all their requirements. It could take six to seven years.”

It’s not a problem that can be ignored. Lopes’s Presbyterian church has started to regularly fill up with new church attendees. The leaders are starting to think about adding a third service. The Monday night Bible study he thought would attract 150 people has been drawing more than 500 a week.

“Everywhere I go, pastors tell me they’ve been receiving members from Pentecostal churches,” he said. “A lot of them tell me that. Everywhere in Brazil.”

Bright Future

Reformed theology came into Brazil “just like the tide coming in—wave after wave,” Johnson said. “What looked like failure was not—it was just another wave coming in. God in his mercy was bringing in waves, and now you’ve got people reading [Dutch Reformed theologian Herman] Ridderbos. You can’t make this stuff up.”

Even the surge of prosperity theology wasn’t a failure, given what followed in its wake.

“Who is leading the young, restless, and Reformed today?” Johnson said. “It’s a steady stream of Pentecostals.”

Who is leading the young, restless, and Reformed today?” Johnson said. “It’s a steady stream of Pentecostals.

Lopes is encouraged by the next generation, though “some discover Reformed faith and want to save the world,” he said with a laugh. “Sometimes they lack a bit of wisdom. . . . When a young Reformed pastor is invited to a non-Reformed church, they want to make the church Reformed in just one day.”

But overall, “the leaders of the Reformed movement in Brazil that I have met are large-hearted lovers of the gospel of Jesus who are not focused on being different, but focused on being faithful to the whole counsel of God,” Piper told TGC.

“There are unhealthy movements that grow out of a need to show that others are mistaken, and there are healthy movements that grow out of a joyful discovery that powerful and precious realities about God and his ways have been obscured, and need to be recovered for the full fruitfulness and joy of God’s people. It seems to me that the Reformed awakening in Brazil is the latter kind of movement.”

Over three trips to Brazil—in 1995, 2011, and 2019—Piper was able to “see the steadfastness of some of the key leaders over a quarter-century in the Reformed awakening. They do not crave instant success, but focus on being faithful for the long haul to the truth of the message. . . . God has raised up leaders who know how to use social media and the internet to spread and deepen the Reformed movement.”

“There is an unprecedented revival in interest for Reformed faith in Brazil,” Lopes said. And “if we believe Reformed doctrines of grace are biblical Christianity, we could say that the Holy Spirit is really working in the lives and hearts of the masses in Brazil. He’s bringing them to know more about the grace of God, the love of Christ, the power of the Holy Spirit, the authority of Scripture—they’re looking for that.”

Why now? Johnson knows what Calvin would say. “God willed it.”