Communism has come back into the spotlight, and it is—as it always has been—extremely divisive. If the church wants to witness to justice and mercy faithfully in our polarized culture, we must understand why communism remains such a powerful topic for those interested in economic justice on both sides of the aisle. And we must have a gospel-centered response.

The Bible compels us to develop an alternative both to the atheistic inhumanity practiced by communism—it murdered 100 million civilians in peacetime—and to the shameless worldly materialism that characterizes so many critics of communism.

If the gospel really does free us from slavery to sin, the church must both proclaim and practice a gospel-centered wisdom about economic arrangements. If it doesn’t, the world has grounds to doubt whether the gospel really is the power of God unto salvation.

Specter Haunting the World

You think communism is old news? I have two words for you: Colin Kaepernick.

On the first day he took a knee, Kaepernick gave a press conference wearing a T-shirt that glamorized mass murderer Fidel Castro. I don’t think my friends on the left understand how fundamentally this act, and his decision to defend Castro when challenged, sabotaged any possibility that his actions might lead to a constructive national dialogue on police brutality (of which Castro was one of the world’s leading practitioners). Kaepernick later “clarified” his praise of Castro, but not in a way that showed any sympathy for his critics—or much concern for the victims of Castro’s atrocities.

Of course the right doesn’t come out of this story looking good, either. Some American police officers are as brutal as Castro, and if we’re against police brutality in Cuba, we ought to be against it here, too. But the right’s response to anything involving communism is often knee-jerk, resentful, and merely destructive. You may not have heard about Kaepernick’s shirt, but I promise you, everyone in my right-leaning neighborhood heard about it, and about Kaepernick’s defense of Castro, that very day. This framed our perceptions of Kaepernick and the national debate over police brutality literally from the start. While some had the grace to respond with civilized discussion and debate, too many merely tuned out, or turned up the anger.

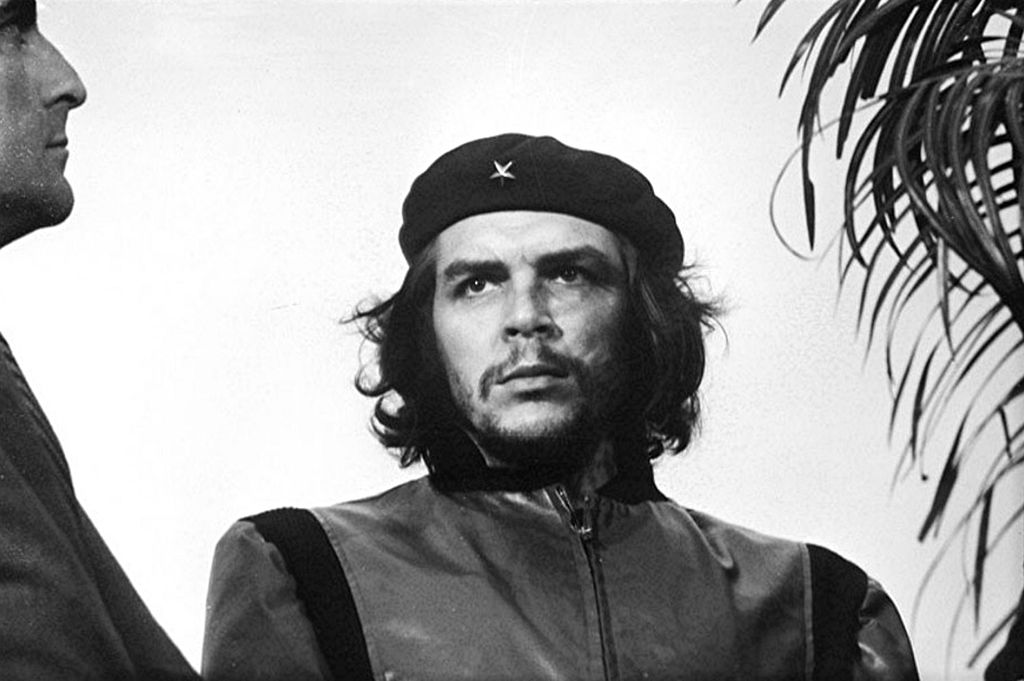

Recent attention to communism in the national media—including American media swooning over North Korean murderers and human traffickers at the Olympics and Vladimir Putin’s claim that communism is biblical—is only the tip of the iceberg. From Che Guevara posters and Hollywood movies glamorizing it to the endless conservative sermons against it, communism remains “the outrage and the hope of the world,” as it was called by Whittaker Chambers, a Soviet spy who was converted to Christ.

If the gospel really does free us from slavery to sin, the church must both proclaim and practice a gospel-centered wisdom about economic arrangements.

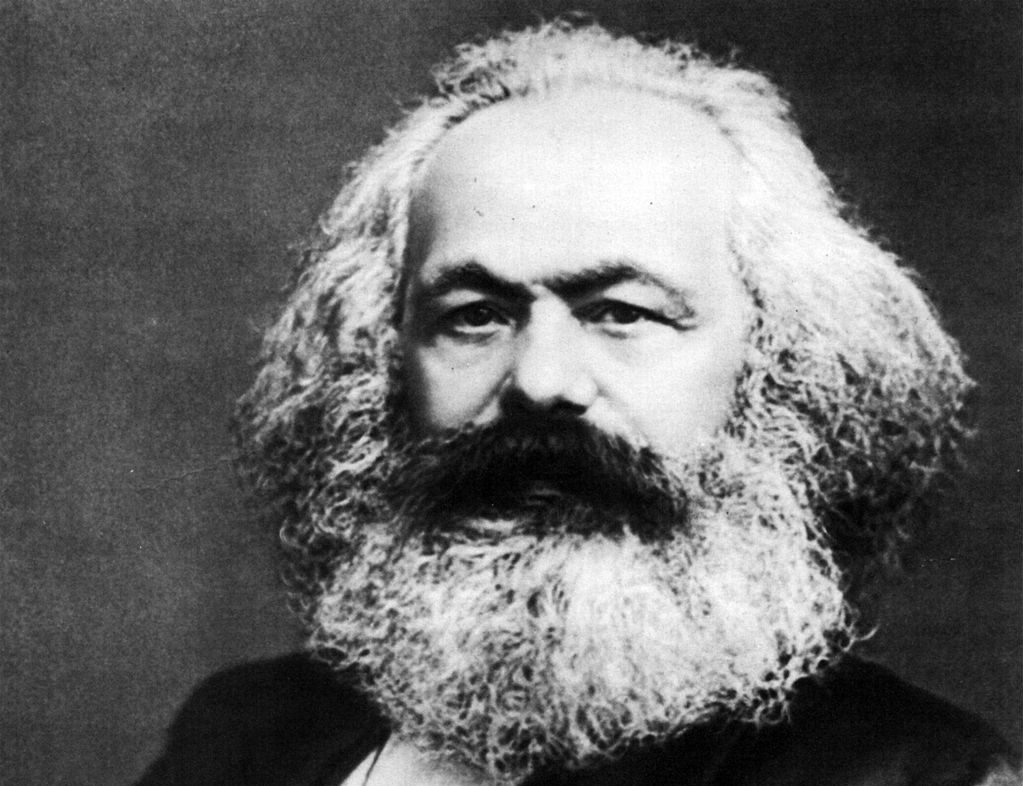

Marx famously said communism was a specter, haunting Europe. Today communism may seem to be dead and gone, but its ghost still haunts the world.

It haunts some as a dream—a vision of possible peace and justice, tragically squandered. It haunts others as a nightmare—a wraith of totalitarian and genocidal horrors, prowling in the dark corners of the culture, awaiting its chance to return from the grave and devour us again.

This mirror-image opposition of attitudes over communism is, as the Kaepernick episode shows, both a symptom and a cause of our cultural polarization. The left demands to know: “Why do you always assume the worst of us? Why do you treat anyone even an inch to your left as some kind of totalitarian monster in the making?” The right demands to know: “Why is it so difficult to get you to agree that mass murder is wrong even when leftists do it? What does that say about how you look at us?”

Building a Better World

Communism haunts the world because the world is submerged in injustice and evil, and it’s desperate to find some path, however perilous, for building a better world. This is why communism will always be plausible and tempting to some. And because it will always be tempting to some, the possibility of its return will always make it dreadful to others.

The church has a true answer to the world’s spiritual bondage. It already knows the right way to escape the power of injustice and evil, and has the assured hope of a better world. Yet communism also haunts the church.

Today communism may seem to be dead and gone, but its ghost still haunts the world. . . . [C]ommunism also haunts the church.

Liberation theology, which puts a Christian face on Marxist social analysis, retains an enormous mystique on the Christian left. This isn’t because left-leaning Christians admire Stalin but because they are profoundly skeptical of the alternative to communism: economic systems built on property and contract rights protected by the rule of law. These systems produce economic growth, but as wealth has grown we’ve also seen a growing worldliness and materialism in our cultures. Christians on the left (most famously Gregory Paul) point to the radical economic community of the church in Acts 2–5 and ask if this doesn’t implicitly delegitimize market systems of price and exchange.

Right-leaning Christians, meanwhile, often seem indistinguishable from secular conservatives. They rail against communism, yet almost none of them seems to have read serious theological analysis of communism—not even from anti-communist Christians like Chambers. In almost every case, their top priority is to protect free markets and economic growth rather than oppose the atheistic inhumanity of the communist worldview. And their zeal to defend free markets often leads them to downplay, or even celebrate, the worldliness and crass materialism that have been associated with economic growth.

Why is the church haunted by communism, even though in Christ crucified we already possess the real answer to the world’s suffering and injustice? Because the church hasn’t put a Christian economic ethic into practice systematically. We need, but don’t know how to develop, an organized and operational Christian economic life. Hence, to fill the hole, some of us have never gotten over the glamour of communism, and others have never gotten over the glamour of the free market.

What’s Not in Acts 2–5

Did the church practice communism in Acts 2–5? That depends on what you mean by communism. The real issue here is not economic but eschatological.

Communism is, at heart, the belief that human ingenuity by itself—without God—can destroy the world’s political and economic evils, if only we’re willing to make the necessary sacrifices. Marx’s complex theories of surplus value, economic determinism, and dialectical history don’t establish that human ingenuity by itself can fix our problems; they presuppose it. They’re built on the assumption that natural reason, without revelation, is capable of understanding human life in a comprehensive way. This involves the assumption that there is no supernatural element in human life.

Communism isn’t a political and economic theory that happens to be associated with atheism. It is atheism—atheism as applied to political and economic systems.

Like fascism, communism is an eschatological theodicy built on, and therefore an idolatrous worship of, political movements. Communism is essentially fascism for rationalists.

If you doubt it, consider that communism was able to thrive, even to the point of almost conquering the world, long after Marx’s theories had been debunked even among communists.

The real dream of communism wasn’t that Marx had fully and finally decoded history, although Marx was foolish enough to think he had. The real dream of communism was that history can be fully and finally decoded. So what if Marx was wrong when he thought he had finished the job? The point is to keep sacrificing everything—conscience, humanity, millions of lives—to ensure we continue working on it. After all, it’s our only hope, because there is no God.

Communism isn’t a political and economic theory that happens to be associated with atheism. It is atheism—atheism as applied to political and economic systems.

This radical eschatological difference is the cause of all the other differences between the church in Acts 2–5 and communism, which we are accustomed to hearing about whenever this topic comes up: Acts 2–5 was an ecclesial event among a faith community that embraced economic sharing out of love, whereas communism is sharing forced on people at gunpoint.

Grammar analysis establishes that the text is describing periodic episodes of radical giving, not an ongoing communalism. Private property was only relativized, not abolished, because the ownership of property was what made the act of sharing it generous (as Peter emphasizes to Ananias in Acts 5:4).

Acts 2–5 took place in an agricultural, household-based economy in which exchanges were neither fully voluntary nor fully coercive because they were bound by kinship ties and closed, tradition-dominated societies; in the modern world, we share political and economic systems with people we don’t know personally and don’t have a common worldview with, creating a stark division between voluntary and coercive (potentially totalitarian) relationships.

Now Let’s Talk about What Is in Acts 2–5

All this isn’t the end of the discussion; it’s the beginning. Realizing Acts 2–5 isn’t communist must not become an anesthetic that numbs us to the powerful testimony of God’s Word against our complacency and materialism.

The temptation to reduce Acts 2–5 to a mere proof text isn’t limited to advocates of communism. Those of us who are concerned about the evils of communism all too often come to this passage merely looking for arguments against communism. It sometimes feels like we collapse the whole story into the single verse of Acts 5:4—as if the early church practiced radical sharing solely for the purpose of giving Peter an occasion to affirm private property rights.

Acts 2–5 was an ecclesial event among a faith community that embraced economic sharing out of love, whereas communism is sharing forced on people at gunpoint.

Seeing the radical sharing of the early church in Acts 2–5, we should feel shamed by their standard of submission to God and love for God and neighbor, not pleasure that we can use the text to score debating points against communism. And we should feel challenged, in a grace-based way, to put this standard into practice today—not only in our own lives and in the life of the church, but as something we offer to the world around us as the only righteous standard of economic life.

This is the failure of the church. Humanly speaking, there are good excuses for it. The old sources of authority that used to be in charge of implementing moral standards in economic life in tradition-bound societies can no longer do so in a world of religious freedom. Political authorities can’t impose this standard, because political power becomes tyrannical when it’s used to restructure the fundamental elements of people’s lives. Church authorities can’t impose it, because religious freedom requires limits on church power. In such an environment, we can still figure out how to practice personal holiness, but we haven’t yet figured out how to bring justice and mercy into public systems like economics.

These good excuses, however, don’t excuse us from the high challenge that God, working through history, has presented the church in the present day. We’ve been complacent about seeking solutions, and our complacency has invited worldly materialism into the church. Worship of money, pursuit of comfort and safety, the mutually reinforcing idols of sloth and workaholism—all are rampant among God’s people.

The church hasn’t simply failed to offer a rightly ordered model of economic life to the world. It has embraced the world’s model of economic life.

The church hasn’t simply failed to offer a rightly ordered model of economic life to the world. It has embraced the world’s model of economic life.

Under modern conditions, justice requires property and contract rights protected by the rule of law. No one benefits from that more than the poor and marginalized. They are always the first ones destroyed wherever these rights are not protected.

But justice requires more than the protection of the laws that structure market relations. It requires a community where people treat each other rightly within market relations. That community ought to be the church, which can model justice in a way that could influence prevailing cultural norms.

Until we practice an economic life that shows the world how the gospel sets us free from evil, communism—as a dream and as a nightmare—will haunt the church and the world.

Church on Notice

Fortunately, there are growing movements to construct Christian economic life within market systems. Some of these are focused on cultivating frugality and generosity. Some are focused on helping the materially poor, the formerly incarcerated, and others facing acute economic challenges transition into jobs and a path to flourishing. Some are focused on economic development, building the relationships of political and economic trust that businesses depend on to get started and grow. Some are focused on destroying systems of injustice and immorality that perpetuate poverty.

At this early stage, it’s hard to say with precision what the new economic life of the church will look like. It’s a topic many wise people are working to understand.

I’m convinced it will involve taking a much more militant stand against the twin idols of fascism and communism. Cultural despair and historical amnesia are already drawing more of our neighbors toward their false promises of redemption through political power. I expect that problem to escalate.

But the heart of the new economic life will be the long, hard, thankless labor of living frugal and generous lives, pushing back the boundaries of poverty, and cultivating fruitful economic cooperation. While we affirm property rights, as Peter does in Acts 5:4, we must live a life in which our property rights are radically relativized as they are for the church throughout Acts 2–5.

We must offer this kind of life to the world as a standard to which it can aspire if it turns to Christ, and in light of which it will become properly ashamed of its evil. But offering this life to the world involves systematizing it as the normal, or at least normative, life of the church.

This challenge isn’t optional for us, because the gospel requires it. To believe that the economic growth facilitated by modern markets must inevitably doom us to lives of worldly vice is pagan fatalism. The gospel is precisely the good news that because of Christ, we can be set free from slavery to worldly passions to live in God’s kingdom of abundant life. If we haven’t yet figured out how to live that kind of life in a world of religious freedom and globalization, we should trust that the Holy Spirit has the power to bring something new and different into the world. And we should get busy following him to build it.

“The Most Practical and Engaging Book on Christian Living Apart from the Bible”

“If you’re going to read just one book on Christian living and how the gospel can be applied in your life, let this be your book.”—Elisa dos Santos, Amazon reviewer.

“If you’re going to read just one book on Christian living and how the gospel can be applied in your life, let this be your book.”—Elisa dos Santos, Amazon reviewer.

In this book, seasoned church planter Jeff Vanderstelt argues that you need to become “gospel fluent”—to think about your life through the truth of the gospel and rehearse it to yourself and others.

We’re delighted to offer the Gospel Fluency: Speaking the Truths of Jesus into the Everyday Stuff of Life ebook (Crossway) to you for FREE today. Click this link to get instant access to a resource that will help you apply the gospel more confidently to every area of your life.