Every October people across the United States and Latin America set aside time for an annual observance—the debate about Columbus Day.

Since the observance first began to be celebrated in the 19th century it has been opposed by a diverse rage of groups, from the Ku Klux Klan to the American Indian Movement to the National Council of Churches. In recent decades, though, the Italian navigator has sparked strong reactions throughout the Western hemisphere, ushering in a new tradition in which we argue about whether he was a bold and brave explorer or a cruel and genocidal colonist (or, as in my view, a mix of both).

This is why, every year, we talk about the myths of Columbus (no, he didn’t think the world was flat) or about what a horrible human being he was (he took slaves on his first day in the New World). While those are worthy topics, we rarely consider the religious angle, specifically how the eschatological views of Columbus have changed our planet.

Columbus Thinks He’s the New John the Baptist

Most people know that Columbus set out on his four voyages across the Atlantic in search of a western route to the Orient. Less known is the motivation for his journeys: Columbus wanted to raise money to finance a new Crusade to retake the Holy Lands.

The last crusade had ended in 1192—300 years before Columbus landed in the New World. He thought it was time to begin them anew. Columbus wrote in his diary that he hoped to find gold and spices “in such quantity that the sovereigns. . . will undertake and prepare to go conquer the Holy Sepulchre; for thus I urged Your Highnesses to spend all the profits of this my enterprise on the conquest of Jerusalem.”

The sailor wasn’t just looking to start a war, though. He believed he had a providential role to play in ushering in the “end of days.” As Reginald Stackhouse explains,

Like others, Columbus believed the world would come to its terminus 7,000 years after the creation. The world was thought to be 5,343 years, 318 days old when Jesus was born. Since then, another 1501 years had gone by, leaving only 155. By that reckoning, the end would be the year 1656. Clearly there was no time for the believers to waste. Jesus had promised that all prophecies would be fulfilled before the end, and his followers should dedicate themselves to accomplishing their part in that fulfillment.

Columbus believed the conversion of all peoples to Christianity and the re-conquest of Jerusalem were necessary preconditions for the Second Coming of Jesus. He also believed he was playing a starring role in the eschatological drama. As he once wrote in his diary, “God made me the messenger of the New Heaven and the New Earth.”

Great(?) Exchange

While it’s tempting to mock his delusions of millennialist grandeur, he may not have been completely wrong. Perhaps God was using him directly, for Columbus played a pivotal role in an event that has forever changed the course of creation: the Columbian Exchange.

The term was coined in 1972 when historian Alfred W. Crosby published his book The Columbian Exchange. The exchange refers to the cultural and ecological ramifications Columbus’s landing in 1492 had on both the Eastern and Western hemispheres of the globe.

Columbus may not have been a “messenger of the New Heaven and the New Earth,” but he was the uniter of the “Old World and New World.” As Crosby says in his book,

The two worlds, which God had cast asunder, were reunited, and the two worlds, which were so very different, began on that day to become alike. That trend toward biological homogeneity is one of the most important aspects of the history of life on the planet since the retreat of the continental glaciers.

Because we live on this side of the historical divide, it’s difficult for modern people to imagine the world (or worlds) that existed before the Columbian exchange. But the widespread transfer of animals, culture, ideas, plants, populations, and technology between the areas has forever changed the planet. It even had a profound influence on theology. As Crosby notes,

The uniqueness of the New World called into question the whole Christian cosmogony. If God had created all of the life forms in one week in one place and they had then spread out from there over the whole world, then why are the life forms in the eastern and western hemispheres so different? And if all land animals and men had drowned except for those on the ark, and all that now exist are descended from those chosen few, then why the different kinds of animals and men on either side of the Atlantic? Why are there no tree sloths in the African and Asian tropics, and why do the Peruvian heathens worship Viracocha instead of Baal’ or some other demon familiar to the ancient Jews? The effort to maintain the Hebraic version of the origin of life and man was to “put many learned Christians upon the rack to make it out.”

The problem tempted a few Europeans to toy with the concept of multiple creations, but the mass of the people clung to monogeneticism. They had to; it was basic to Christianity.

Potatoes and Maize and Infectious Disease

The theological controversy unleashed by Columbus was a mere ripple, however, compared to the tsunami effect of the interchange of flora and fauna. Consider, for example, just two of the hundreds of plants that were involved in the exchange: potatoes and maize.

The potato didn’t arrive in Europe until 1570. But wherever the potato was introduced—particularly in Europe, the United States and the British Empire—the population grew rapidly. As Jeff Chapman notes, before the widespread adoption of the potato, France managed to produce just enough grain to feed itself each year. The potato made it possible for countries in Europe to increase their food security. The Irish population, for instance, doubled to 8 million between 1780 and 1841, by which time almost one-half of the Ireland had become entirely dependent upon the crop. One study found that the potato “had a significant positive impact on population growth, explaining 12 percent of the increase in average population after the adoption of the potato.”

Maize also had a similar effect on Europe, Africa, and Asia, leading to rapid population growth. “If suddenly American Indian crops would not grow in all of the world, it would be an ecological tragedy,” Crosby wrote. “It would be the slaughter of a very large portion of the human race.”

While the New World was providing plants that would increase populations, the Old World was sending over infectious diseases that would devastate entire peoples. Some of the diseases that were introduced included bubonic plague, chickenpox, cholera, diphtheria, influenza, leprosy, malaria, measles, scarlet fever, smallpox, typhoid fever, typhus, and yellow fever.

The Columbian exchange may have led to a population explosion in the Old World, but for many indigenous peoples in the New World, the arrival of Columbus truly did usher in the “end of days.”

If You’re Reading This, It’s Because God Used Columbus

The profound effects of the Columbian exchange, both positive and negative, are nearly incalculable, and necessarily complicate our reaction to Columbus’s influence. We can and should, for example, both lament the extraordinary loss of life that resulted from the exchange and also be grateful for the lives it helped to create (including, most likely, both yours and mine). How then do we judge the influence of the world’s most controversial sailor?

Perhaps the best we can do is marvel at the profound and mysterious actions of providence, and let Columbus’s example serve as a reminder that, “Many are the plans in the mind of a man, but it is the purpose of the Lord that will stand” (Prov. 19:21).

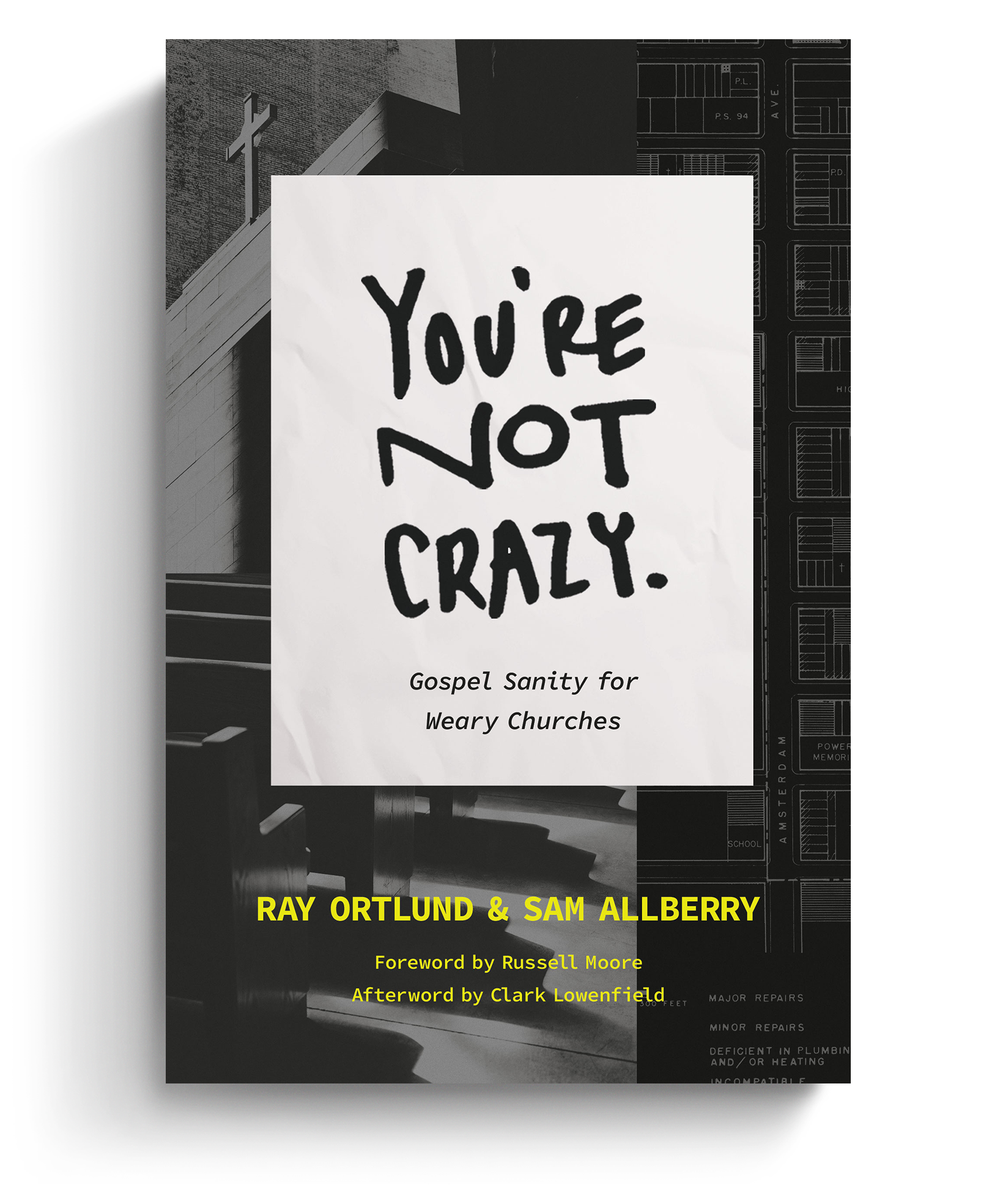

Are You a Frustrated, Weary Pastor?

Being a pastor is hard. Whether it’s relational difficulties in the congregation, growing opposition toward the church as an institution, or just the struggle to continue in ministry with joy and faithfulness, the pressure on leaders can be truly overwhelming. It’s no surprise pastors are burned out, tempted to give up, or thinking they’re going crazy.

Being a pastor is hard. Whether it’s relational difficulties in the congregation, growing opposition toward the church as an institution, or just the struggle to continue in ministry with joy and faithfulness, the pressure on leaders can be truly overwhelming. It’s no surprise pastors are burned out, tempted to give up, or thinking they’re going crazy.

In ‘You’re Not Crazy: Gospel Sanity for Weary Churches,’ seasoned pastors Ray Ortlund and Sam Allberry help weary leaders renew their love for ministry by equipping them to build a gospel-centered culture into every aspect of their churches.

We’re delighted to offer this ebook to you for FREE today. Click on this link to get instant access to a resource that will help you cultivate a healthier gospel culture in your church and in yourself.