It almost sounds like a humblebrag.

“Is the Unemployment Rate Too Low?” CNN asks.

“How Low Can Unemployment Really Go?” The New York Times headline reads.

In May, the national unemployment rate dropped to an 18-year-low of 3.9 percent. Iowa did even better with 2.5 percent. And in Marion County, about 45 minutes southeast of Des Moines, unemployment dropped to a flat 2 percent.

But that fantastic unemployment rate—combined with more kids going to college and the misperception that manufacturing jobs don’t require skill or education—is wreaking havoc on Marion County’s manufacturing industry.

“We’ve got 106 job openings posted right now,” said Vermeer Corporation outreach and community relations manager Teri Vos.

Vermeer makes large-scale farming and industrial equipment—things like balers, directional drills, and compost turners. The place is run by a family that’s serious about faith and work, and has been puzzling over how to fill those job openings.

Because the trouble isn’t just a lack of workers. It’s also a lack of training.

“Today’s manufacturing is not my dad’s manufacturing,” said Vermeer board chair Mary Andringa, whose father Gary Vermeer started the company in 1948 after inventing the wagon hoist. “There is technology in everything.”

Until now, Vermeer employees have been quietly learning as they go, getting trained on new technology as it arrives. But that’s left a perception gap: people still think of manufacturing as low-skill, low-paying work. High school students and their parents dream of a college degree, not a spot on the assembly line.

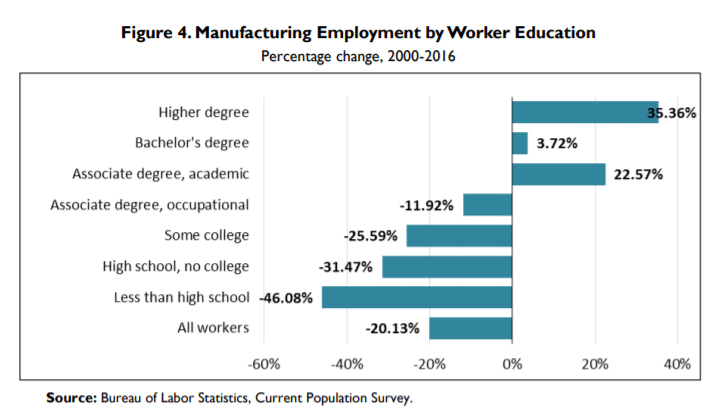

That’s not just at Vermeer. Across the country, manufacturing employment (defined as plants, factories, or mills that characteristically use power-driven machines) for those without a high-school degree fell by 46 percent from 2000 to 2016. At the same time, jobs for those with an associate degree or more has risen.

“[W]hat would arguably help underemployed U.S. workers the most is retraining, so that their skills match the requirements of the better-paying jobs in U.S. factories,” The New Yorker observed.

Or training high-school graduates right off the bat, before they spend tens of thousands of dollars on a college education they may not need, the leadership at Vermeer thought. They started to dream—not just about filling those 106 open job spots, but about returning dignity to the work of manufacturing.

“We believe each person has unique skills and gifts given by God,” Andringa said. “Our goal is to help people to be their very best.”

It’s why they offer continuing education classes to their employees. It’s why they promote from within whenever possible. And it’s why they’ve just introduced the country’s first high-school registered apprenticeship in welding for manufacturing.

The two-year program begins junior year of high school. Students get paid to work at Vermeer, under the supervision and mentorship of another welder. That experience will count toward a two-year general studies degree at a local community college, which the students can finish after they graduate from high school.

We believe each person has unique skills and gifts given by God.

It seems like a perfect, obvious answer—one that harkens back to blacksmith shops and clockmakers, but this time with an official certificate from the American Welding Society and an associate degree from Des Moines Area Community College.

It also seems replicable—perhaps it could solve more problems than just Vermeer’s. At least, Iowa hopes so. The project is an experiment for the entire state. (And perhaps the country. Jeff Weld, who ran the Iowa Governor’s STEM Advisory Council that commissioned Vermeer to pilot the project, is now Trump’s senior policy adviser for STEM education.)

“We intend to develop the same thing for engineering technicians, and the Career Academy we’re working with plans to add apprenticeships for nursing assistants and the culinary arts,” Vos said. “Who knows where it could go from there?”

She does, actually. “We’re starting to have adults ask us, ‘When can we sign up?’ It’s definitely something we’re already exploring. We think it’s doable.”

As Vermeer literally writes the playbook for the program, they’re doing it the same way they do everything else—based on the four P’s that Andringa reached for more than 30 years ago when asked if she was going to run the company with her father’s Christian principles.

Reformed Roots

Gary Vermeer’s Reformed roots were thick; he was born into the Dutch-settled town of Pella, Iowa, in 1918. He farmed like his father before him, but tinkered more. When he was 25, he invented the wagon hoist that catapulted him into manufacturing. The company followed with a string of useful inventions for farmers and others who relied on the outdoors to make a living, including a self-propelled irrigation system, a tree spade (the first machine to dig and transport large trees), and the round hay baler.

Gary was also active in his church—joining its 1955 plant and directing plays as fundraisers. (First one: Hans Brinker.)

His denomination—the Christian Reformed Church—has long preached a holistic faith-and-work philosophy.

“Avoiding any division between sacred and secular, we encourage endeavors in any sphere of human activity: art, media, publishing, law, education, labor relations, caregiving, agriculture, business, social justice, and politics,” the denominational website says.

So Gary—and his brother and his cousin, who were also early managers at Vermeer—brought their faith to work, focusing heavily on caring for employees and customers, developing excellent products, and stewarding his finances. Ten years in, they started the Vermeer Charitable Foundation with percentages of the company’s annual profit. (The foundation has since given away millions to causes such as local hospitals, Christian education, and disaster relief.)

By the early 1980s, Gary’s children were taking over the reins.

“I had an employee say to me, ‘We know what your dad was all about. But what about you kids?’” Andringa said.

Passing Along Faithful Work

Andringa doesn’t like to call Vermeer a Christian company. (“I don’t think you can ever say a business is Christian. It’s not a person; it’s an entity.”) Instead, she and her family try to “manage by biblical principles.”

Andringa used to be a teacher (kindergarten and preschool). And she’s heard a lot of sermons. So she used an easy-to-remember alliteration for Vermeer’s foundational values: principles, people, product, and profit.

Three of those are Lee Iacocca’s, she acknowledges. She had just read his book. But Andringa’s had a different slant—each one tied back to the Bible.

“Principles” means standards such as honesty, good stewardship, and doing for others what you’d want them to do for you. “People” means valuing everyone—employee, boss, customer—as uniquely gifted and worthy of development. “Product” means producing quality goods that make a difference in the world. And “Profit” means giving generously and putting resources back into the financial stability of the company.

These aren’t just nice things to say at employee orientation or to dealers to assure them of Vermeer’s integrity. Gary built the four Ps into Vermeer before they were even called “the four Ps,” and the company has had plenty of time—70 years—to hammer out what they mean.

Integration of Faith and Work

The ways Vermeer has found to pursue the four Ps are almost too many to chronicle. As soon as you think you’re done, somebody remembers another one.

The company chases innovation and integrity in its products and services. (“We’re never going to put out junk,” Andringa says.) Since most of its machinery deals with the physical environment—drilling, trenching, and processing rocks and dirt and trees—Vermeer emphasizes care for creation both in designing responsible equipment and also in donating foundation funds to environmental protection causes.

Its best inventions were created to meet the needs of someone they knew. Gary opened the company to help area farmers who needed a better way to get corn out of their wagons. He invented the hay baler to help a friend who couldn’t find enough hired help for his cow operation. And the company came up with a surface excavation machine when a customer in Italy needed to transform rocky ground into a vineyard.

The company’s leadership also “goes above and beyond to take care of their people,” Vos said. Vermeer throws parties for employees regularly (family-friendly affairs with food and sometimes petting zoos and inflatables), but its care is also much more substantial. It built a health clinic and pharmacy on campus where employees can go cheaply and conveniently. It added an early learning center where employees can drop off children, then run over during breaks to feed their babies or eat lunch with older children.

Vermeer also encourages savings in 401(k) plans with a company match. Employees can donate to help other team members in financial trouble, get paid for volunteer time, and ask the Vermeer Foundation to give to causes they’re passionate about.

“Sometimes those tangible benefits and unique ways Vermeer is showing they care for their people—that makes a person say, ‘Hey, there’s something about this company that’s a little different,’” Vos said. “That opens the door [to conversations about faith]. Plus, there is so much Vermeer has done in giving back to the community, from churches to schools to different mission programs—all of that very quickly piques the curiosity of people, whether they’re familiar [with Christianity] or not. Soon they want to know more about it.”

For those who do wonder, Vermeer provides an easy access to an answer.

Workplace Chaplains

“I pioneered the position,” said Kevin Glesener, who responded to Vermeer’s first ad for a chaplain in 2007. He’s an evangelical United Methodist (“I’ve probably preached in more Reformed churches than Methodist churches”). When he came to a shrinking Methodist congregation in a nearby small town in Iowa in 1992, attendance jumped from 90 to more than 300. (“We were busting at the seams,” he laughs. “We had small groups meeting in closets.”)

His favorite part was the one-on-one pastoral care, so when he finished his 15-year run at the church, the Vermeer chaplaincy sounded intriguing. He was grateful to get the job because he didn’t have any formal experience being a chaplain. Then again, Vermeer didn’t have any experience with the position either.

“I kind of patterned the program after Tyson Foods,” which started their chaplain program in 2000, Glesener said. “And after a couple of years here, I was burned out and overwhelmed.”

It wasn’t that Tyson’s example was bad—just the opposite.

The job is based on conversations, so Tyson chaplains keep a regular schedule (“Be in a certain plant at a certain time each week”) and chart whom they talk to and when. It gives structure and accountability to an otherwise fluid and ambiguous job description.

And it’s remarkably effective. After showing up over and over again, getting to know people’s names, and asking about family members, Glesener had earned the trust of many of Vermeer’s 3,000 employees. They started asking him to pray for them, asking for advice, asking him to conduct their weddings, asking him to preside over their funerals.

“After two years, I was working 60 to 80 hours a week and having health issues,” Glesner said. “It was so overwhelming.”

Vermeer hired a second chaplain in 2010, a third in 2014. They’re bringing a fourth on board this year, along with part-time chaplains at their plants in South Carolina and South Dakota.

“Every month our chaplains have personal, confidential, pastoral discussions with between 800 to 1,000 people,” Andringa said. The chaplains show up at all three shifts. They’ve been at hospital beds and divorce proceedings and jail cells. They’ve been asked for financial advice and marriage counseling and tips for dealing with family members.

“It’s definitely a cost,” Andringa said. And it is, because chaplains don’t produce products that can be sold. The financial value they add—if any—is almost impossible to calculate. Are employees more productive if they have access to a chaplain? Vermeer has no idea.

“It’s hard to know the before-and-after, because there’s a lot of stuff going on,” Andringa said. But she knows that “having them on the floor—in the flesh, not on the phone—is so impactful for our employees.”

Including, she hopes, the newest employees.

Millennial Purpose

“Everyone wants a purpose,” Vos said. “Sometimes people say millennials want more of it. I don’t agree. I think all generations of people have always wanted a purpose.”

But she does think that millennials—who will make up 75 percent of the work force by 2025—are changing the way people think about their occupations.

“The change I see is that living out a sense of purpose doesn’t just happen one day a week, or in a certain area of my life, or when I go home from work,” she said. “There is a new sense of integration, where that sense of purpose has to be very much a part of what I do every day at work. It’s not something we set aside to do on our own time anymore.”

So Vermeer has had to articulate purpose, she said. It’s not that they were purposeless before (“Any manufacturing company is likely doing something to fill a need”), but now they’re making connections out loud.

“We have a huge product line of big yellow iron machinery,” Vos said. “There was a time when we talked about taking care of our customers and doing big work. But now we’re going one step further and sharing what these machines are doing to change the world.”

Trenchers help bring clean water to remote villages. Forage equipment helps farmers better steward their land. Drills give classrooms in remote areas access to the internet.

“We’re really intentional about sharing these stories with our team members, so they know the weld they’re putting on the machine will go out the door into the world and could really change the life of a whole community somewhere,” she said. “Making connections doesn’t have to be difficult. We just have to be intentional about remembering why we’re all here.”

Purposeful Apprentices

Vos uses that same intentionality to think about the new apprenticeship program, including how manufacturing ended up with too few workers. Part of it is the unemployment rate. But another part comes from misperceptions about vocation and success, she said.

“A lot of us—either as students ourselves or as parents—have pushed toward a four-year degree,” Vos said. She’s right: The number of college graduates has risen from 4.6 percent of Americans in 1940 to 33 percent in 2016.

“It seemed like if you didn’t have a four-year degree, you couldn’t be successful,” she said. “And that really did have effects on the workforce. All of a sudden you wake up one day and say, ‘Where have all our technical skills gone?’”

She sees students who have spent time and money on college, only to find their skills and passions were elsewhere. “We have high-school students in our area who know a four-year degree isn’t for them, but they can flounder a little sometimes,” she said. “They don’t know what their goal is then.”

Vermeer’s apprenticeship program offers a way to enter the workforce after high school with purpose, she said. Instead of stumbling into a manufacturing job, high school students can now follow a well-considered and carefully crafted path.

And that approach—which comes with one-on-one mentorship with a seasoned welder, official certification from the American Welding Society, and a two-year general studies degree—is giving dignity back to a job that has been overlooked.

Vermeer’s emphasis on the dignity of manufacturing is already spreading. Andringa chairs the Iowa Business Council, and has played a large role in Iowa Governor Kim Reynolds’s Future Ready Iowa initiative to provide 30,000 work-based apprenticeships or internships by 2025. The bill passed both houses unanimously this spring, though some politicians cautioned that coming up with the $18 million Reynolds asked for could be difficult.

The state support has been crucial; without its resources and publicity Vermeer’s program wouldn’t have gotten far. (Vermeer’s first apprentice signed up for his program like a star quarterback signing with Nick Saban at Alabama—news media snapped pictures while the governor and U.S. Secretary of Labor Alexander Acosta looked on.)

“The Department of Labor and Education and the governor have all come to the table with interest in partnership and cooperation,” Vos said. “What has been really challenging in terms of developing apprenticeships in years past has become attainable fruit at this point, because we were asked to be the pilot in the state launch and had resources to put toward this.”

She doesn’t want to say that Vermeer is leading the apprenticeship conversation across the nation. But it’s definitely participating.

“We’re trying to be unique or original thinkers about that pipeline from high school,” Vos said. “Success comes in so many different shapes and sizes. That’s a conversation we’re having more often here. . . . All work has dignity.”

“The Most Practical and Engaging Book on Christian Living Apart from the Bible”

“If you’re going to read just one book on Christian living and how the gospel can be applied in your life, let this be your book.”—Elisa dos Santos, Amazon reviewer.

“If you’re going to read just one book on Christian living and how the gospel can be applied in your life, let this be your book.”—Elisa dos Santos, Amazon reviewer.

In this book, seasoned church planter Jeff Vanderstelt argues that you need to become “gospel fluent”—to think about your life through the truth of the gospel and rehearse it to yourself and others.

We’re delighted to offer the Gospel Fluency: Speaking the Truths of Jesus into the Everyday Stuff of Life ebook (Crossway) to you for FREE today. Click this link to get instant access to a resource that will help you apply the gospel more confidently to every area of your life.