Good Omens, a new series on Amazon Prime Video, is probably the most interesting and directly theological television show since The Good Place. This is not to say these shows are theologically accurate; just that they are asking theological questions in interesting, often entertaining ways.

Some Christians might interact with shows like Good Omens only on the level of condemnation, calling it blasphemy and demanding its cancellation, as one Christian group recently did. But as Glen Scrivener pointed out in a recent video commentary on Good Omens, this is not the most helpful approach. We can and should acknowledge that the show is irreverent and rife with theological errors, but as Scrivener points out, the show’s makers have faulty theology in part “because [Christians] have preached faulty theology, we have lived faulty theology.”

There is certainly space and time to engage shows like Good Omens in the name of theological accuracy, calling foul on its errors and pointing out its own inconsistencies. But we ought first to engage it with humility, recognizing that if the world has misunderstood Christianity, then perhaps we’ve been communicating it poorly.

Breath of Fresh Satire

Good Omens, the shared handiwork of Neil Gaiman and the late Sir Terry Pratchett, hit unsuspecting bookshelves in 1990. I first stumbled across this cheeky little tome midway through a ravenous binge of Pratchett’s work—Good Omens was dedicated “to the memory of G. K. Chesterton, a man who knew what was going on,” and I was accordingly hooked.

Which might seem strange, given that the book’s raison d’être is arguably to satirize my faith tradition. Moreover, as noted above, the story is admittedly riddled with astounding theological errors. But then again, so are all-time classics Paradise Lost and The Divine Comedy. And after all, this is a comedic take on the end times written by two non-Christians, so if we approach it in search of exegetical rectitude, a headache will be our only reward.

This is a comedic take on the end times written by two non-Christians, so if we approach it in search of exegetical rectitude, a headache will be our only reward.

But most importantly, I love this story because, like all good satire (which is the only kind Pratchett wrote), it tells the truth. God, I grant, is infallible. But his people are not, and if Gaiman and Pratchett have some laughs at our expense, then it’s because we are, on occasion, quite laughable.

For the Love of the World

The story follows Aziraphale (angel) and Crowley (demon), who have been on earth since The Start. By the time our tale begins, they’ve gone quite native. Oh, they do their jobs, of course—minor miracles, perfunctory temptations, memos sent dutifully up the line (or down, as it were)—but mostly they keep their heads down and enjoy life.

Imagine their consternation, then, when word comes down the line (or up, as it were) that the time has come for life to end. All of it. Forever. Faced with the prospect of losing the world they’ve called home for the last six millennia, the unlikely duo hatches a plan to forestall Armageddon. Hijinks (and low ones) ensue.

Crowley (David Tennant) and Aziraphale (Michael Sheen) love the world of man and the works of man—whales and dolphins, fast cars and good wine, Albert Hall and sushi. They love it all and declare it good.

Aziraphale’s dismay upon hearing his bookshop has burned down is enough to break any bibliophile’s heart, and the sight of Crowley on his knees before the smoking wreckage of his vintage Bentley feels more like the end of the world than anything in Left Behind. Yet even when their prized possessions lie smoldering, they keep fighting, for it’s the world they love, not just their place in it.

Their love for the world is not naïve. They remember the days of Noah. They watched the crucifixion. They lived through the Reign of Terror and the Spanish Inquisition. They’ve witnessed 6,000 years of genocide, racism, theft, arson, London traffic, and selfies. They know the world is broken. They love it anyway.

Far too often, professedly Christian eschatology sounds less like the apostle John and more like the Lord Beelzebub (Anna Maxwell Martin) in Good Omens: “It is written. There shall be a world, and it shall last for 6,000 years and end in fire and flame.”

God created a good world. He loves it. He died for it. John’s Apocalypse foretells he will renew it, not destroy it (Rev. 21:5). And a faith that brushes off creation as only so much dross to be burned away at The End is Gnosticism, not Christianity, and thoroughly deserving of every satirical jab Gaiman and Pratchett take at it.

Simply Ineffable

Good Omens reaches its climax, not on the fields of Megiddo, but on the tarmac of an airbase in the English countryside. The Kraken has risen from the deep, the four horsemen of the Apocalypse have ridden as scheduled, signs and wonders are in plentiful supply, the armies of heaven and hell have assembled for the final showdown . . . and the young Antichrist (Sam Taylor Buck) refuses to start the war. He’s an otherwise normal 11-year-old boy, after all, and he can see the absurdity in burning down the world just to prove whose gang is better.

Flabbergasted, Gabriel (Jon Hamm) and Beelzebub both insist that Armageddon commence. This is the great plan, after all, the whole reason for the creation of earth, the point to which all of history has been sliding since “Let there be light,” and they’ll be damned/blessed if a snot-nosed kid is going to stand in the way of the Great Plan.

At which point, Aziraphale pipes up, “Is that the Ineffable Plan, as well?” Gabriel tries to brush him off, insisting the two are one and the same, but Crowley swaggers over as well, saying, “I mean, everyone knows the Great Plan, yeah? But the Ineffable Plan is ineffable, isn’t it? By definition, we can’t know it.” Perhaps it’s not actually the end of the world the Almighty’s after—who can say?

Later, as he’s sharing a bottle of wine with Aziraphale on the field (well, park bench) of victory, Crowley muses, “Angel . . . what if the Almighty planned it like this all along? From the very beginning?” His heavenly friend simply shrugs, “Could have,” and takes a swig.

Is the God of Good Omens distant and detached, or so intimately involved in every movement of creation that the divine will is indistinguishable from reality itself? Crowley and Aziraphale aren’t too proud to say they don’t know.

Now, Christians are not at a total loss when it comes to knowing the mind of God, given the considerable pains he’s gone to in order to reveal himself in his Word. Yet one of the things he’s taken particular care that we know is the fact that we do not know everything:

For my thoughts are not your thoughts,

neither are your ways my ways, declares the LORD.

For as the heavens are higher than the earth,

so are my ways higher than your ways

and my thoughts than your thoughts. (Isa. 55:8–9)

Let us never, brothers and sisters, confuse the fact of God’s sovereign plan with the myth of our perfect understanding of that plan. For when The End truly does come, we have the assurance that many will say, “Lord, did we not prophesy in your name, and cast out demons in your name, and do many mighty works in your name?” And these poor souls will hear, “I never knew you; depart from me, you workers of lawlessness” (Matt. 7:22–23).

Let us never confuse the fact of God’s sovereign plan with the myth of our perfect understanding of that plan.

Such passages should inspire deep humility in our theological disputes. Such verses should lend profound gentleness to our ethical debates. And such knowledge should leave us terrified of placing the success of our tribe above the commands of God.

If the church is to have a more effective witness in today’s world, it will not be because we lash out any time we are faced with critique. Rather than boycotting any TV show with bad theology, perhaps we should let it prompt in us reflection: where has our theological witness been so off, so confusing, so off-putting, that it would lead to the sort of satire we find in Good Omens?

As Christians, we can be confident in our faith without being arrogant. We can be humble without being wishy-washy. We can contend for our interpretations even as we are open to being proven wrong.

After all, in the words of Crowley, “It’d be a pity if you’d thought you were doing what the Great Plan said, but you were actually going directly against God’s Ineffable Plan.”

That wouldn’t be funny at all, in The End.

Are You a Frustrated, Weary Pastor?

Being a pastor is hard. Whether it’s relational difficulties in the congregation, growing opposition toward the church as an institution, or just the struggle to continue in ministry with joy and faithfulness, the pressure on leaders can be truly overwhelming. It’s no surprise pastors are burned out, tempted to give up, or thinking they’re going crazy.

Being a pastor is hard. Whether it’s relational difficulties in the congregation, growing opposition toward the church as an institution, or just the struggle to continue in ministry with joy and faithfulness, the pressure on leaders can be truly overwhelming. It’s no surprise pastors are burned out, tempted to give up, or thinking they’re going crazy.

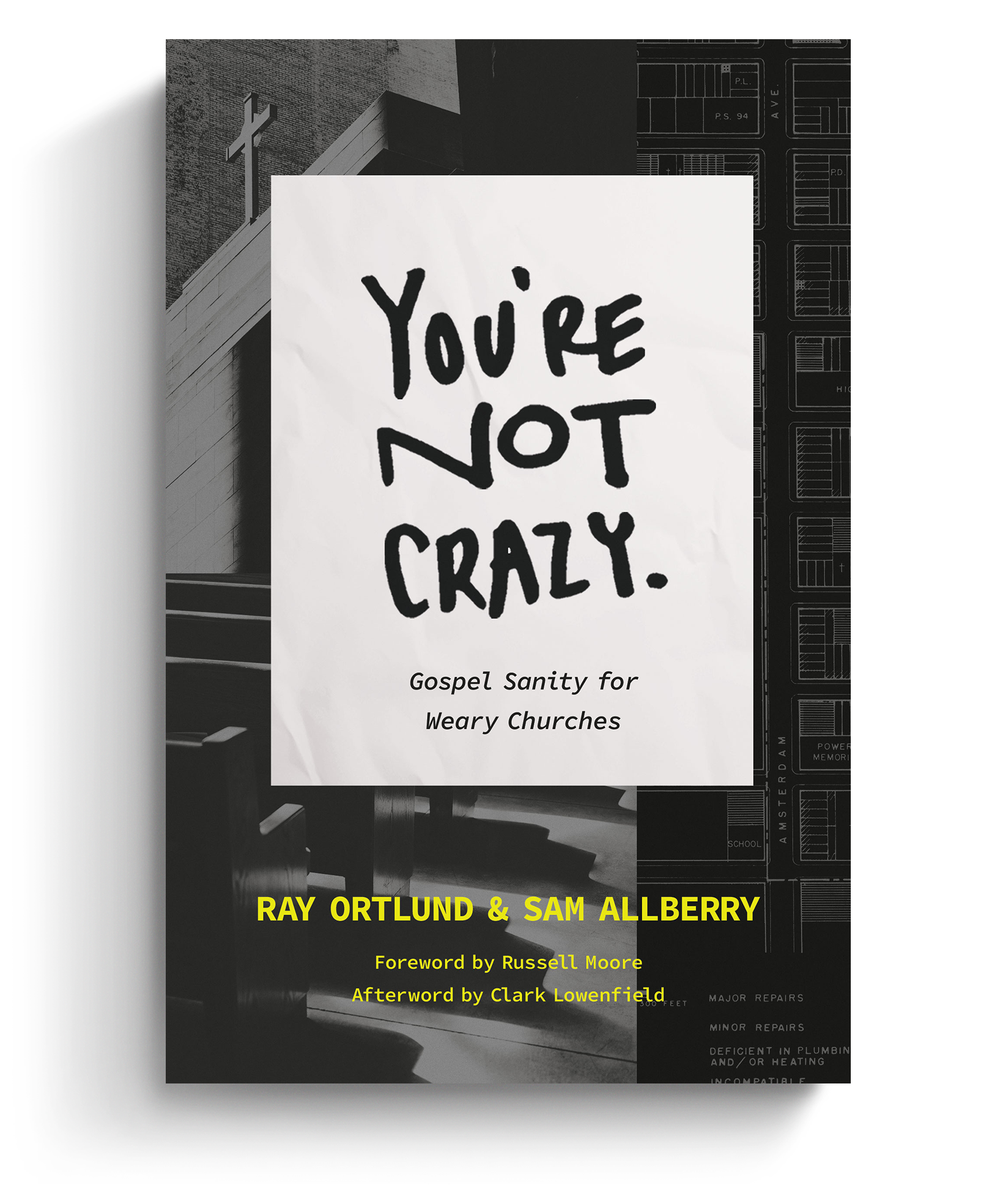

In ‘You’re Not Crazy: Gospel Sanity for Weary Churches,’ seasoned pastors Ray Ortlund and Sam Allberry help weary leaders renew their love for ministry by equipping them to build a gospel-centered culture into every aspect of their churches.

We’re delighted to offer this ebook to you for FREE today. Click on this link to get instant access to a resource that will help you cultivate a healthier gospel culture in your church and in yourself.