The Israelites’ exodus from Egypt is a major narrative referenced throughout the Bible, and it’s known by millions around the world. But many question whether the exodus really happened, due to a presumed absence of archaeological evidence and general skepticism about the historical reliability of biblical narratives. It’s often viewed as a myth or a legendary compilation constructed from segments of different historical events spanning various periods, all merged into one edited story.

One common argument against a historical exodus is that there’s supposedly little or no evidence for such an event. However, archaeological and historical evidence points to the reliability of the biblical account of the exodus and the settlement in Canaan.

Hebrews in Egypt

The first component of this momentous story is the claim that Hebrews moved to and resided in Egypt for many generations. In a broad sense, it’s obvious from archaeological discoveries that Semites from Canaan had migrated to Egypt and settled in the northeastern Nile Delta region (Goshen), as demonstrated by specific forms of pottery, burial customs, tools and weapons, inscriptions, historical records, a Levantine breed of sheep, wall paintings, and even imported deities.

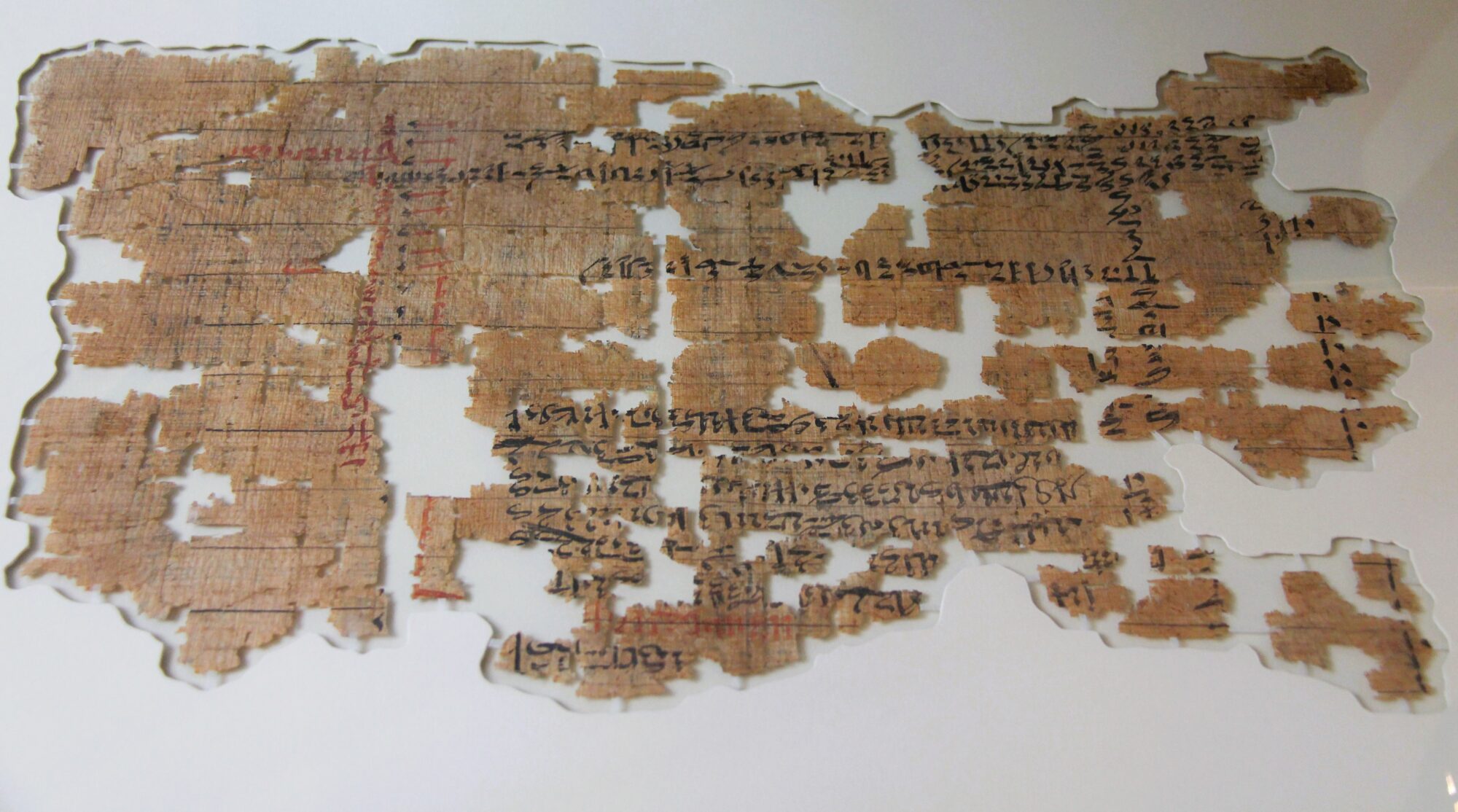

Moreover, there’s evidence of people who can be specifically identified as Hebrews residing in Egypt prior to the exodus. An Egyptian list of household slaves on Papyrus Brooklyn 35.1446, probably originating in Thebes from approximately the 17th century BC, contains the names of more than 30 Semites, who like Joseph were given new Egyptian names (Gen. 41:45).1

These are some of the Hebrew names on this papyrus:

| Hebrew Name in Papyrus Brooklyn | Occurrence in Scripture |

| Shiphrah | Exodus 1:15 |

| ‘Aqoba (Jacob/Yaqob) | Genesis 25:26 |

| Dawidi-huat (David) | 1 Samuel 16:13 |

| Esebtw (“herb”) | Deuteronomy 32:2 |

| Hayah-wr (Eve) | Genesis 3:20 |

| Menahema (Menahem) | 2 Kings 15:14 |

| Ashera (Asher) | Genesis 30:13 |

| Sekera (Issakar) | Genesis 30:18 |

| Hy’b’rw (Hebrew) | Genesis 39:17 |

Other names associated with Hebrews—Jacob-El (Yaqub) on scarabs from various locations and perhaps Jesse (Yushay) on an ostracon from Deir el-Bahri—have been found in Egypt from contexts before the exodus.

There was also a policy of widespread enslavement of Semites or Asiatics implemented in Egypt. This began with Ahmose I and the founding of the 18th Dynasty, around the time when “there arose a new king over Egypt, who did not know Joseph” (Ex. 1:8–14; 5:4–19). This enslavement included mudbrick production, construction projects, and agriculture.2

These accounts of Hebrew slavery appear to coincide with large storage facilities built from mudbrick during the early 18th Dynasty, found during excavations at Rameses (Tell el-Daba) and Pithom (Tell Retabeh), along with an Egyptian royal palace on the river banks that dates from around this time (1:11; 2:5–10, NIV; Acts 7:20–22).3

Date of the Exodus and the Pharaoh

A thorough investigation of a historical exodus, however, requires knowing precisely when the exodus happened. Scripture includes clues both obvious and subtle.

First and foremost, the book of Kings records that the 480th year after the exodus was the year when Solomon began the process of building the Jerusalem temple, around 967 BC (1 Kings 6:1). This aligns with Jephthah’s claim that the Israelites had been in the promised land for 300 years, approximately five decades before Saul, around 1100 BC (Judg. 11:26). We also see that 19 generations had elapsed from the exodus to the construction of the temple, which at an average of 25 years for each generation comes to about 475 years (1 Chron. 6:33–37).

Further, because information from several temple dedication inscriptions in the ancient Near East demonstrates that people counted actual solar years in this type of context, we can therefore demonstrate that the Israelites were recording real timelines.4 This helps us count back from the temple’s construction to reasonably date the exodus to roughly 1446 BC. Thus, we can look in a specific time frame for external evidence that might corroborate the Exodus account.

At that point in Egyptian history, Amenhotep II had recently become pharaoh. His predecessor, Thutmose III, had ruled for more than 40 years (see Ex. 2:23; 4:19; 7:7; Acts 7:30). This, along with other events that fit the Exodus narrative, indicates a historical exodus would’ve occurred during his reign.

Ancient Egyptian documents, inscriptions, and archaeological findings also indicate the mysterious death of the pharaoh’s firstborn son, the military’s decline, the abandonment of his palace in the Nile Delta, the attempted erasure of Hatshepsut, and a slave raid into Canaan.5 Additionally, in the third century BC, Manetho, an Egyptian priest and historian, named an Amenhotep (Amenophis) as the pharaoh of a Hebrew exodus. Furthermore, an intriguing Egyptian poem known as “The Admonitions of Ipuwer” might preserve memories about the time of the Exodus plagues.6

These connections with the exodus are subject to debate. However, there’s additional archaeological evidence of Israelites outside Egypt around this time—first as nomads and then as conquerors and settlers in Canaan.

Hebrew Wandering and Appearance in Canaan

Finding archaeological evidence for nomads in ancient history is difficult because of their transience and the fragility of their material culture. Nevertheless, two Egyptian inscriptions mentioning the “nomads of Yahweh” from the Soleb temple of Amenhotep III appear to describe the wandering Israelites around 1400 BC, between the exodus and the conquest of Canaan.7

These inscriptions indicate the Egyptians were familiar with the personal name of God (Yahweh) and with the Israelites, the only people in ancient times known to have worshiped Yahweh. The timing of around 40 years after the exodus, the location of these people between Egypt and Canaan, and their status as nomads support the wandering of the Israelites after leaving Egypt (Ex. 5:1; Num. 14:14).

Soon after, the Israelites appeared in Canaan, conquering many cities and settling in the region. Evidence related to the historicity and date of Canaan’s conquest may be communicated in some of the correspondence of various Canaanite kings with the pharaoh. These cuneiform tablets, called the Amarna Letters, mention the Habiru, a group of outsiders, who are waging war and taking cities by both force and guile.8

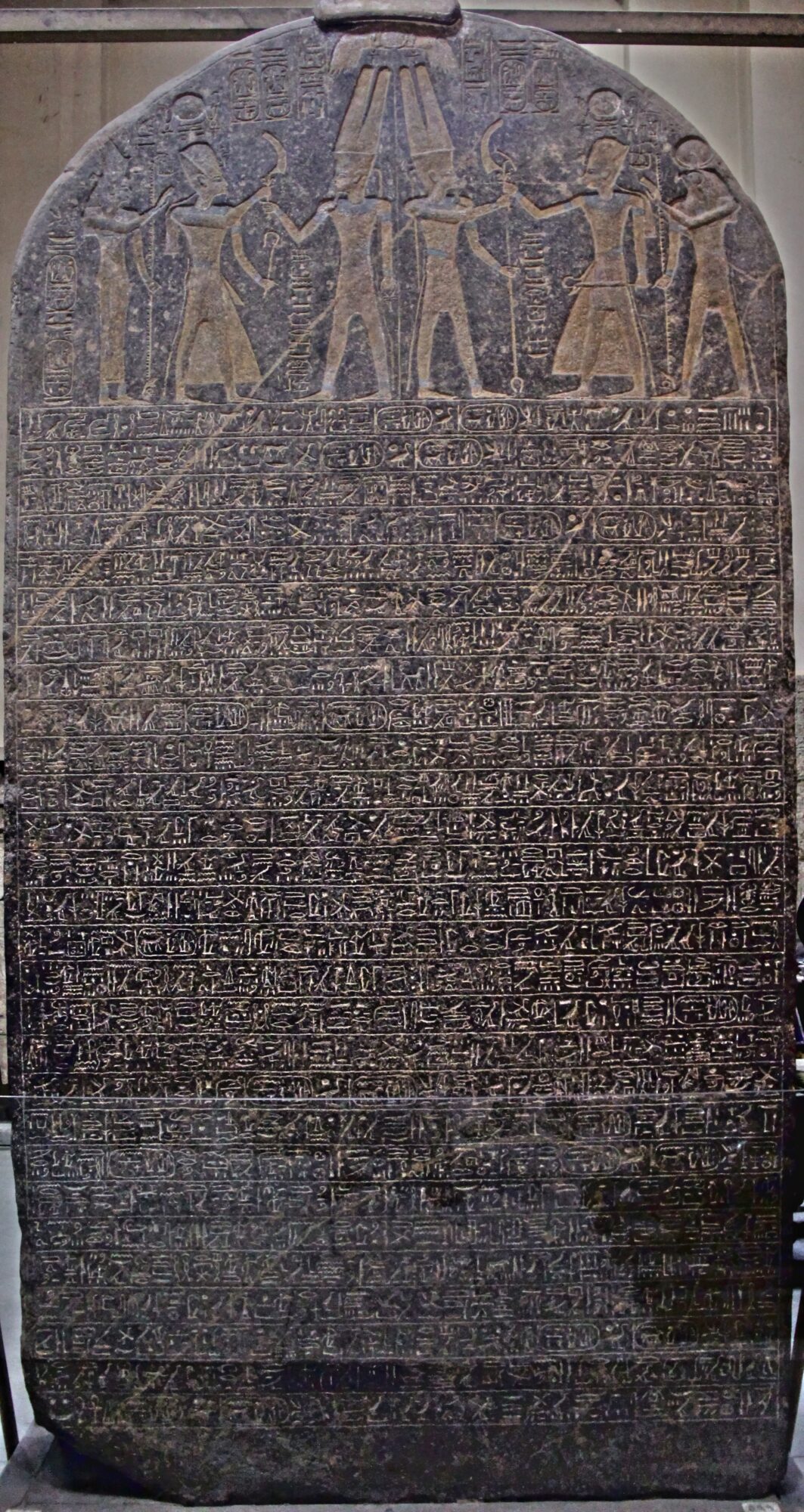

Additionally, archaeological evidence of the destruction linked to the Israelite conquest has been cited at key cities named in the Joshua narrative, including Jericho, which shows massive fire destruction, fallen walls, no looting, and long abandonment around 1400 BC.9 Subsequently, settlement evidence from many towns demonstrates a new group of people had appeared in Canaan who had unique architecture, pottery, diets, and religious traditions. The Merneptah Stele of the late 13th century BC calls this people “Israel,” and it’s the only group of people in Canaan mentioned by the pharaoh.10

These archaeological discoveries and many others support the historical reliability of the biblical narrative about the exodus and eventual settlement in Canaan. These findings can give us greater confidence in God’s word, as we appreciate his provision for his people.

Free Book by TGC: For Graduates Starting College or Career

Many young people are walking away from Christianity—for reasons ranging from the church’s stance on sexual morality, to its approach to science and the Bible, to its perceived silence on racial justice.

Many young people are walking away from Christianity—for reasons ranging from the church’s stance on sexual morality, to its approach to science and the Bible, to its perceived silence on racial justice.

TGC’s book Before You Lose Your Faith: Deconstructing Doubt in the Church is an infusion of hope, clarity, and wisdom in an age of mounting cynicism toward Christianity.

For anyone entering college or the workplace and looking for a timely reminder of why Christianity is good news in a skeptical age, make sure to get your FREE ebook Before You Lose Your Faith today!