What does it mean to be a confessional church? When making our case for a particular doctrine, is it fine to reference our confession of faith, or would it be best to just stick to Scripture? Isn’t the Bible enough for Christians in establishing our doctrine and practice? Should we demand church members subscribe to a particular view of a third-level doctrine?

These are among the practical questions that sit at the heart of confessional Christianity. I put these questions to Ligon Duncan, a longtime confessional Christian and TGC Council member. Duncan, former pastor of the historic First Presbyterian Church in Jackson, Mississippi, now serves as chancellor of Reformed Theological Seminary.

Is it biblical for the church to write and use confessions of faith?

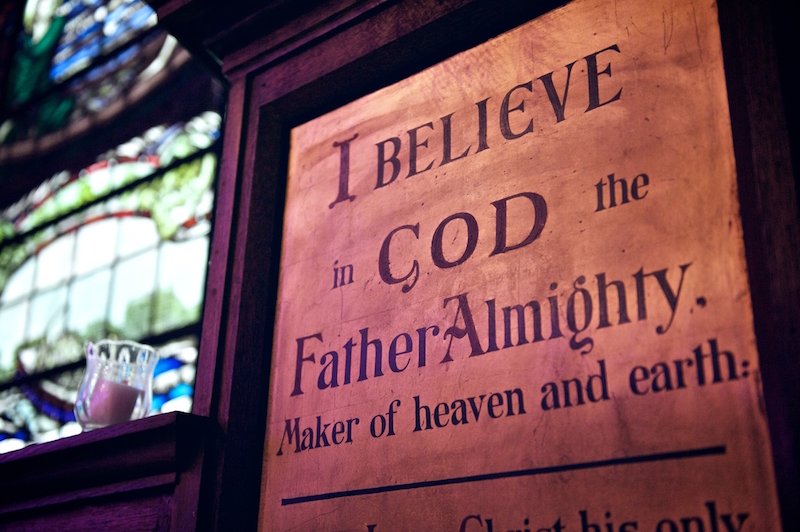

Yes! It is absolutely biblical for a church to use a confession of faith. The famous shema of Deuteronomy 6:4—“Hear, O Israel: the LORD your God, the LORD is one”—is a confession of faith. It affirms the two ideas most basic to the Israel’s religion: that Yahweh exists, and that he is the one true God. In the New Testament, Paul calls these fundamental affirmations “trustworthy sayings.” Such basic statements highlighting the fundamental commitments of God’s people are found throughout Scripture.

What about writing confessions of faith? Again, yes. If you look at the history of creeds and confessions, you’ll see that human-created creeds and confessions arose out of the church’s desire to be faithful to Scripture’s clear teaching. Whenever false teachers were appealing to the Bible and twisting it to suit their own purposes, Christians defended the truth by clearly articulating their scriptural convictions with the most faithful language they could muster—and which the false teachers could not affirm. For instance, the word homoousios is not found in Scripture, but is designed to convey an indisputably scriptural idea about the deity of Christ and the consubstantiation of the Son with the Father. Arius and his company were unwilling to affirm it, and therefore that word was used to uphold biblical truth against heresy.

What does it mean to be a confessional Christian?

A confessional Christian is defined by their affirmation of faith in accordance with the historical confessions of the church.

Such accordance with the confessions and creeds of the past protects us against idiosyncrasy, unbiblical separatism, “chronological snobbery” (in the words of C. S. Lewis), and schismatic tendencies. It keeps us operating within the communion of saints. It ensures we give appropriate voice to the silent majority of 2,000 years worth of orthodox Christians who have gone on to glory as the church triumphant—and who can no longer speak for themselves. They speak to us through the creeds and confessions they’ve left behind.

Confessional Christians such as Presbyterians, Anglicans, and Reformed Baptists are often accused of prioritizing “man-made statements” over the Bible. One theologian even called any demand for subscription to a confession or creed a “rape of the soul.” How should we respond to such accusations?

Our response to accusations is often determined by the sincerity of the person making them. The “rape of the soul” is inflammatory language meant to protect an unbiblical stance on the freedom of conscience. However, when people have sincere questions about confessionalism, I don’t want to rebuke them; I want to address their concerns legitimately.

First, it’s impossible not to be confessional. Everyone is confessional; now, whether it’s written and whether it’s biblical is another matter. And everyone is a theologian, even the people who say theology is bad. It’s always better when we’re clear on our theology, and for that nothing beats writing it down on paper. Writing does not guarantee infallibility, of course, but it does make it easier to determine whether the doctrine we’re confessing aligns with Scripture.

Second, the point of a confession of faith isn’t to put something above Scripture. The point of a confession is to ensure the public teaching of the church is as close to the teaching of Scripture as possible. When we don’t write down our theology and confess it publicly as a church, it leads not to healthy freedom but to unhealthy restriction.

Considering these points together, imagine if a Baptist and a Presbyterian were to come to a Church of Christ congregation and say, “We’re going to teach on the meaning of baptism today, first from the Baptist Faith and Message and then from the Westminster Confession of Faith. Since the Church of Christ has no creed but Christ, and we all affirm the Bible, we can teach here, right?” The duo would quickly be told otherwise. Why? Because everyone has a creed, even—and especially—those who say they don’t.

How should a confession be used in a denomination or institution? In a local church?

Confessions have historically been used in three ways. First, they’ve defined and defended doctrine and thereby protected the church from false teaching.

Second, they’ve been used for catechesis: training and equipping believers with a well-rounded overview of Bible teaching on the main points of religion.

Third, they’ve been used for doxology and worship. Many churches affirm the Apostles’ Creed or Nicene Creed in public worship. Though the main uses of a confession are the first and second, all three together show us how confessions are meant to be employed.

What makes a good confession of faith?

Confessions of faith are always rooted in history. There’s no such thing as a confession without context. They are always situated in the theological and cultural context of their time. Why do the confessions of Nicaea, Constantinople, and Chalcedon focus so much on the Trinity and the deity of Christ? Because those ideas were under attack at the time.

Why does the Apostles’ Creed labor to affirm the goodness of creation, and the reality of the human life and body of Jesus Christ? Because Gnosticism was denying these truths. We could go through every confession in church history and show that contemporary controversy, along with cultural and theological context, contributed to the content, shape, and topical coverage of the confession. We’ll never have one final human-composed confession, since there are always new challenges that call on the church to confess biblical truth publicly.

What makes a good confession of faith? It must be both comprehensive and concise. You want to cover all the matters the church needs to confess as briefly and clearly as possible. It should be comprehensive enough to defend the truth and catechize the people, but also leave room for liberty for disagreement on non-primary issues. Take, for example, the Westminster Confession, which is far more comprehensive than more recent confessions from various denominations. And yet, even as comprehensive as it is, it leaves a lot of room for good people to disagree on not-unimportant matters. Being comprehensive and concise allows the church to make a full, robust affirmation of biblical truth without becoming so detailed that people who hold to a high view of Scripture and orthodox theology are excluded.

What about denominations, institutions, and churches that reject the use of confessions? Does this put them in a position of vulnerability? How does being confessional strengthen a denomination, organization, or local church?

I think denominations, institutions, and churches that reject confessions are made vulnerable precisely in the two areas that creeds and confessions help us most. They’re vulnerable to failing to adhere to biblical doctrine and to teaching a clear system of biblical doctrine to their people. This can be proven over and over again in church history.

As groups rejected the more robust confessionalism of the period and opted for more minimalistic statements of faith, unbelief or heterodoxy always followed. The result was either a rationalistic downgrade like Unitarianism, which stemmed from New England congregationalism but rejected the confessionalism of earlier generations, or a heterodox downgrade that became a cultish theology.

What might constitute a misuse or overuse of a confession of faith?

It’s not a matter of overuse, but misuse. If the confession or creed is biblical, how could one possibly overuse it? But a confession’s authority does not reside in itself. The authority of the confession resides in its faithfulness to articulating biblical truth. In doctrinal controversy, as helpful as it is to cite the church’s confessional testimony over the last 2,000 years, we must ensure we are always arguing from the Bible as our final rule of faith and practice.

As Sinclair Ferguson said to me years ago, “It makes all the difference in the world whether we believe something because we read it in Berkhof and whether we believe something because we read it in Romans.” It may be that Berkhof is saying the same thing Romans is saying, but the reason we ought to believe it is because it’s in the Bible.

Confessions themselves aren’t inherently authoritative; they point to the final authority of God’s Word. We should always be able to argue from the Bible. Confessions only help us say, “We believe and teach this because we believe the Bible—and by the way, 20 centuries of Christians agree with us.” So we misuse the confession of faith if we appeal to it as the final authority.

How should confessions of faith be used in the local church?

Confessions can be of tremendous help in the church, but we must be very, very careful. When Reformed Theological Seminary was founded in the 1960s, many of our students graduated and went into Presbyterian churches assuming the leaders and congregations believed the Westminster Confession. After all, the elders and deacons had subscribed to it. Those students were stunned, then, to learn many of those people had never read the Westminster Confession—nor did they like some of the things it taught.

Regardless of our denomination, none of us should go into a congregation assuming our people know their confessions of faith. We do not live in a theological age. Rather, we live in an age focused on feeling and deeds rather than creeds—as the saying goes, “Deeds, not creeds.” Therefore, we should not assume our people know these documents, adhere to them, or even like them.

I would say the first thing a pastor ought to do when entering a confessional church is discern whether the leaders know their confession’s teaching. Start training church leaders—both formal and informal—to ensure they are thoroughly acquainted with the church’s confession.

Hopefully, by the time this is accomplished, the pastor will have discerned whether the congregation knows and values the teaching. If they know and value it somewhat, then the confession can be used as a didactic device. The pastor could preach through the Apostles’ Creed, or if you’re a Baptist, a series on the Baptist Faith and Message 2000 or the 1689 London Baptist Confession of Faith. Just be aware that if the confessions are not used carefully, they can expose a theological rift in the congregation.

Involved in Women’s Ministry? Add This to Your Discipleship Tool Kit.

We need one another. Yet we don’t always know how to develop deep relationships to help us grow in the Christian life. Younger believers benefit from the guidance and wisdom of more mature saints as their faith deepens. But too often, potential mentors lack clarity and training on how to engage in discipling those they can influence.

We need one another. Yet we don’t always know how to develop deep relationships to help us grow in the Christian life. Younger believers benefit from the guidance and wisdom of more mature saints as their faith deepens. But too often, potential mentors lack clarity and training on how to engage in discipling those they can influence.

Whether you’re longing to find a spiritual mentor or hoping to serve as a guide for someone else, we have a FREE resource to encourage and equip you. In Growing Together: Taking Mentoring Beyond Small Talk and Prayer Requests, Melissa Kruger, TGC’s vice president of discipleship programming, offers encouraging lessons to guide conversations that promote spiritual growth in both the mentee and mentor.