It took around eight hours for Renaldo Hudson to kill Folke Peterson.

Peterson, 71, was a retired carpenter living in an apartment on Chicago’s South Side. Hudson, 19, lived in the same apartment building with his father, who was the janitor.

Hudson knocked on Peterson’s door on June 6, 1983, pretending he was there to fix a light fixture. When Peterson turned his back, Hudson attacked, certain the man was hiding money.

From around 7 p.m. to 3:30 a.m., Hudson stabbed Peterson 60 times, pausing occasionally to search for money and watch TV. After Peterson was dead, Hudson hid the knife in a chair and started the body on fire to hide his tracks.

It didn’t work. He was caught immediately, turned in by his aunt who noticed his blood-stained clothing and several unfamiliar items—old watches, some silverware, a decanter.

“I was sure he had a million dollars somewhere,” said Hudson, now 53. Turned out, Peterson had $4.

In prison, Hudson was trouble, attempting escapes and fighting with other inmates. A jury sentenced him to death. But even on death row, he didn’t calm down.

“Even the serial killers and rapists on death row didn’t want to be with me,” he said. His behavior was bad enough to get him kicked off death row, earning him a transfer to another prison. After an altercation with an officer there, he was given a year in isolation.

Then one day, Hudson heard a Louis Farrakhan tape, in which Farrakhan asked, “What are you good for? Or are you good for nothing?”

Wanting to be good for something, Hudson turned to Farrakhan’s Nation of Islam. Soon after, an officer told him he’d take a day off his isolation punishment for every Bible verse he memorized.

Hudson started with “Jesus wept,” but eventually memorized so many he dropped his isolation time to just 90 days. With the words of God in his heart, he became a Christian (though was still considered so dangerous that he was baptized with his shackles on).

“I’m in prison—literally—but prison is no longer in me,” Hudson, now 53, told TGC. He’s been behind bars for 34 years, his good behavior so steady for the last 23 that he’s been moved to a lower-security prison and allowed to serve as the chaplain’s assistant. (His death sentence was commuted when Illinois Governor George Ryan cleared death row in 2003.)

Last month, Hudson was part of the first class to graduate with a four-year diploma from Divine Hope Reformed Bible Seminary.

Because of this training, Hudson preaches sermons to fellow prisoners. He evangelizes on the yard. He prays “all the time.” And the man who dropped out of school in sixth grade has studied Greek and Hebrew, memorized parts of the Heidelberg Catechism, and written papers on systematic theology. (“To be Reformed is to be informed,” he says.)

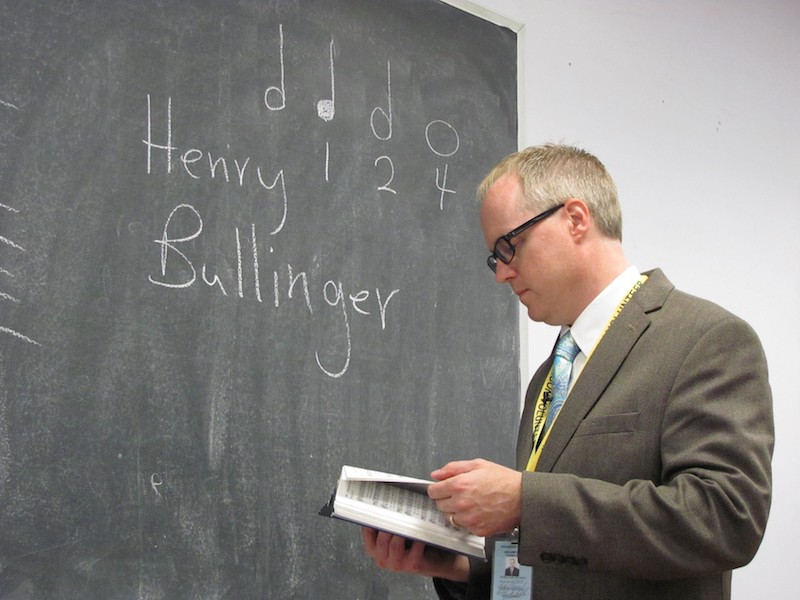

“What we’re trying to do is something in a long history of theological education, going back to the Netherlands, going back to Calvin’s Geneva, where we had a concern for intelligent piety,” Divine Hope administrator and professor Nathan Brummel said at the graduation ceremony, one where the graduates wore prison blues and the invitation-only audience was locked in.

From the beginning, “our concern was not just to have a lot of smart students,” he said. “We want to have students who know God in his triune majesty and his marvelous grace, but we also want to have students who love God and love their neighbor and walk in all godliness. . . . God has answered that prayer.”

In the last half decade, Divine Hope has grown from one faculty member to four, from one prison to five, from 25 students to 110. Classes have expanded to include a program on fathering, a Bible study at the women’s prison, and a Spanish-language worship service.

“When I came to prison I could not read and write,” Hudson said. “Today they’re giving me a four-year degree in Christian studies. That’s to the glory of God. If they would’ve said to me the day I was arrested, ‘If you can spell can, you can go home,’ I’d still be in that bullpen. But today I can talk about transubstantiation. I can talk about systematic theology. I know about the Belgic Confession.”

Divine Hope

Danville Correctional Center, where Hudson lives, is a medium/high-security facility about 150 miles south of Chicago and half a mile from the Indiana state border. Four X-shaped dormitories house around 1,800 men whose crimes range from aggravated assault to rape to multiple murders.

For years, the inmates at Danville had been visited by Manny Mill—a convicted felon mentored by Chuck Colson. After his release from federal prison for fraud, Mill founded Koinonia House National Ministries in Wheaton to help released prisoners transfer to civilian life.

After a while, he started to bring along members of the United Reformed Churches in North America (URC)—a small, historically Reformed denomination—in the southern suburbs of Chicago and nearby northwest Indiana. They would drive down on Sunday mornings to hold worship services.

Those visits grew into friendships, and eventually the URC members wanted to assist Danville’s recently released men through Mill’s Meet Me at the Gate initiative. But they ran into a border snag. More than 80 percent of Illinois prisoners remain supervised after their release and can’t easily cross state lines, even ones a half-mile away.

The churches were stuck. Now what?

The answer came at a Reformed conference the churches held in the prison. One inmate attendee told them, “We need a means to study systematic theology.”

“We were blown away,” Jon Hoek, a URC member who would become Divine Hope’s first board president, told a Calvin College reporter. “It made us rethink what we were doing and started us thinking in a new direction.”

So several men from the churches (members of the future Divine Hope board), along with Danville warden Keith Anglin, headed south to check out the Louisiana State Penitentiary, which houses the most celebrated seminary in the nation’s prison system.

The New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary has been operating there since 1995, when warden Burl Cain, facing drastic cuts, invited them in. Today, more than 250 graduates work at 31 self-supporting churches inside the walls.

“They’re like indigenous pastors,” Brummel said. The effect is exactly what you’d expect: The existence of trained pastors among a prison population helps create safer prisons with lower incident rates and, as a result, lower operations costs, according to Baylor University researchers.

Impressed, the Illinois visitors began kicking around the idea of starting their own seminary. It took three years, but in 2012, Brummel taught his first class to 28 inmates. He started with the doctrine of God, explaining his attributes and decrees.

“They all know their Bible,” Brummel said then. “In some respects, they put us to shame. What’s missing is an understanding of the doctrine of the covenant, how it provides the architectonic structure for all of God’s revelation in Christ, how it ties the biblical message together.”

So he started providing it.

School in Prison

Divine Hope’s classes are rigorous, but the standards aren’t the same as The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary or Westminster Seminary. That’s because almost none of its students has been to college; in fact, most didn’t finish high school.

The prison offers GED classes, and the seminary requires a high school diploma or GED before entrance. It runs like a Bible college, with courses in systematic theology, biblical theology, hermeneutics, Christian ethics, Christian history, practical theology, and the biblical languages.

“The majority of students aren’t prepared to deliver sermons,” Brummel said. “They’re prepared to be godly fathers and husbands, to be contributing members of a church. When they get out, they’ll be faithful workers.”

But a few do deliver sermons on the two Sundays a month Divine Hope is allowed to lead worship in the prison chapel.

“When I get up there, I lose myself,” said Christopher Douglas, who is taking a practice preaching class and has preached four times so far. The 28-year-old loves the pulpit but also the field; he has a burden to serve other young men and single moms. (His own single mother was gang-raped at 15; Douglas was the result.)

Hudson has preached eight times, and even delivered a message on sola gratia during this year’s two-day Reformed conference in May. About 75 prisoners attended, which is how many chairs the chapel will fit. Conference attendance—as well as class enrollment—has to be requested by prisoners ahead of time, and approved both by seminary faculty and also prison officials.

Divine Hope hands out one-year, two-year, and four-year diplomas. The school isn’t accredited, and in some senses, the graduation doesn’t change anything—the men will live in the same cell, eat at the same cafeteria, serve out the same sentence. But it does open opportunities for them to take on additional responsibility at Divine Hope.

“Men who have shown themselves to be godly and embraced Reformed theology, with a good reputation in prison and an academic ability, will be prepared to be peer instructors,” Brummel said. That’s the next step for the graduates—teaching seminary classes and facilitating Bible studies in the mission field of incarceration.

All of Divine Hope’s faculty members see their work that way—they labor in a foreign, forgotten population kept separate by walls and razor wire. “The prison systems are like a vast chain of islands spread throughout the country,” Brummel said, referencing Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s The Gulag Archipelago. Behind the walls, more than 2 million prisoners in America eat, sleep, shower, go to the gym, wash their clothes, eat meals, get their hair cut, and buy groceries.

They also self-segregate, eating lunch and spending time with men who look like them, speak their language, and share their gang affiliation. Their wars on the streets follow them into prison; even on death row, the Gangster Disciples still held meetings, Hudson said.

The seminary helps to break down those walls—not all the way down, Brummel says, but at least partially. The first graduating class features two white, two black, and two Hispanic men. And when asked which gang he belonged to, Douglas—who sports a gang tattoo under his right eye—says he’s a Christian now. It’s been so long since he said his former gang’s name that it feels weird to him.

Conversion

That change in Douglas is deep. Since childhood, his family groomed him to be part of the Almighty Black P. Stones, an African-American gang founded in 1959. His uncle and stepfather were gang members; his mother was affiliated as well.

It wasn’t an easy birthright. Douglas’s mother helped him to steal, and to buy and sell drugs for money to pay the bills. His stepfather beat them both. When Douglas was in grammar school, the window at the end of the school hallway looked out onto the street corner where his mother stood selling drugs. Other kids would crack jokes about her, which led to fights, which led to suspensions.

Douglas tried to get out, at one point holding down two jobs and even attending church. But after a while he strayed back to the life, starting with smoking cigarettes and talking to old friends and ending with a $2 million bond and a 17-year sentence for aggravated battery. After he was incarcerated, in one summer alone, Douglas’s Chicago neighborhood buried 23 people and put three more in critical condition. One of those killed was his younger brother.

Douglas came to faith in prison, after picking up a Gideon’s Bible out of sheer boredom. When he left the gang, he also abandoned the physical and financial security they provided. “My security is in God, not in gang affiliation,” says the man who now spends his time thinking about how to minister to troubled young inmates or how to combat religious insincerity.

Every seminary student has a story like Douglas’s—unique in details but all nearly unbelievable in their brokenness. Hudson, for example, survived both the accidental death of his twin brother and also a purposeful bullet through the chest from another brother, who then shot seven other family members, killing two.

“Many of our students come from unstable home environments,” Divine Hope professor Paul Ipema said. “Many were exposed to abuse of one sort or another—physical, sexual, or emotional. Many have never known a regular father figure.”

They tend to be introduced to substance abuse early, often as young as 10 or 12, and often by their parents, he said. “It’s not an excuse, but it certainly adds context to understanding where they’re coming from.”

Many of their crimes involve gang violence, such as one four-year graduate, who was 16 when he flashed his gang sign, then shot and killed a 17-year-old rival.

Earl Wilson, who earned his two-year diploma from Divine Hope this year, is perhaps the most notorious. Wilson was the bodyguard for Chicago’s kingpin drug dealer in the 1980s, and was convicted of setting up his assassination. (In May, his son was charged with the high-profile killing of Cook County Judge Raymond Myles.)

“I am serving two life sentences,” he told the graduation audience. “But even while that is my plight today, my soul is at peace with the Lord.”

Wrestling with emotion, Wilson grew quiet, then motioned Hudson forward to finish the speech.

“Divine Hope has been such a blessing to me in helping me develop a godly perspective toward the hand of God in all situations,” Hudson read. “To all the brothers here, keep God as your focus point. Stay the course the Lord has clearly set before you.”

Indiana Expansion

Handing out four-year diplomas is a milestone for Divine Hope, which seems to be hitting milestones every few months.

Two years after Brummel taught his first class at Danville, Divine Hope hired another professor and expanded to Indiana State Prison (ISP) in northern Indiana. The maximum-security facility was built in 1860 to house Civil War prisoners; now it holds more than 2,000 men, 720 of them convicted of murder.

ISP was originally reluctant to host Divine Hope—which doesn’t ask for funding, just space and time with the inmates—but relented after a nudge from then-Governor Mike Pence’s administration.

Pence’s administration also gave Westville Correctional Center a push toward Divine Hope. Fifteen miles south of ISP, Westville houses more than 3,000 short-term male inmates. It releases about 50 prisoners a week, and before they go, tries to teach them skills in areas such as horticulture, automotive repair, or building maintenance.

Westville officials “opened up a secluded old chapel classroom” and offered Divine Hope’s course to anyone. The seminary had 40 students, but many didn’t want to be there, Divine Hope professor Ken Anema said.

Anema struggled through, and that “crack in the door” was enough. Divine Hope began gaining a good reputation, and within six months was moved into a different program, which required more work from inmates to enroll.

“I make it clear in the interview that we expect them to read, write, and memorize,” Anema said. “I tell them, ‘We are going to have two hours of work outside of class for every hour in class.’ I work out the multiplication—how many hours that is a week—and ask them if they’re wiling to put the time in.”

Not everyone is. Attendance dropped to 11, “but we’re accomplishing more with those 11 than we were with the 40,” he said. The students almost always have their work done, and come with an assigned verse or catechism question and answer memorized.

A few months after Divine Hope opened at ISP and Westville, it started a Bible study at Rockville Correctional Facility, the largest women’s prison in Indiana, with about 1,200 inmates. On Mondays, Divine Hope offers classes on how to reconnect with family; on Fridays, volunteers from area Reformed churches lead the Bible study.

Two years ago, 27 female inmates attended Divine Hope’s six-week summer class on the Heidelberg Catechism.

“When I signed up for the six-week study course offered by Divine Hope, I didn’t know what a catechism was,” Laurel wrote after it was over. “The first day of class we learned Lord’s Day 1, and I came to an understanding. I was glad and relieved that I was not my own, but I belong to Jesus.”

Laurel, 44, is serving her fifth sentence for drug abuse. “I was ashamed that I could not stop using drugs, and I am sure my children and mother thought I was a lost cause,” she wrote. “Now I know that I could never do anything alone. There is nothing in me that is not sin. I have prayed every day, more than once, since the first class for the Holy Spirit to reside in my body.”

Illinois Expansion

Eighteen months ago, Divine Hope hired a third faculty member to help carry the load. This spring, the seminary added a fourth professor and a fifth prison. Stateville Correctional Center is a maximum-security state prison less than an hour from downtown Chicago. The 1,600 or so men are generally serving life or multiple decades; inmates have included serial killer Richard Speck, “perfect crime” killer Nathan Leopold, and William Balfour, who murdered Jennifer Hudson’s mother, brother, and nephew.

For 13-odd years, two members of Covenant Orthodox Presbyterian church used to visit Stateville regularly, bringing in Reformed literature and hosting a Bible study a few times a month. But when one passed away and another retired, Covenant’s access was restricted to a visit every 90 days.

Anxious to get back in more often, Covenant contacted Divine Hope and proposed a partnership. If Divine Hope’s educational access could open the doors, Covenant would supply the professor.

Deal, Divine Hope said. So in April, Covenant pastor and Divine Hope’s newest faculty member, Brett Mahlen, taught his first class there. (“Did anybody tell you this room used to be a gas chamber?” the guard said when he showed him to his classroom. “The electric chair is right down the hall.”)

Saturdays are busy for Mahlen: He conducts a Bible study on John for two men in isolation, then teaches a Divine Hope class. Once or twice a month he adds a worship service.

On Mondays he teaches a three-hour class on the Westminster Shorter Catechism.

“I want to get to every cell and teach as many men as I can,” said Mahlen, who has permission to visit the men anywhere on site. “I live, eat, sleep, and breathe Reformed theology in the Shorter Catechism, and I’m happy to talk about it constantly with anyone who wants to talk about it.”

Challenges

“It’s amazing that we’re in this many prisons this fast,” Mahlen said. “We have to praise God and hope it continues.”

Sometimes that quick growth is exhausting.

“We don’t want to grow too fast, or we’ll lose a sense of development and spread ourselves too thin,” Anema said.

It’s a real possibility. The seminary leadership’s five-year plan—written in 2014 when it was three years old—was ambitious, outlining goals such as adding more faculty, developing a presence at more prisons, providing two-day conferences, and connecting those who are released with local Reformed or Presbyterian churches.

They’re well on their way, with barely a chance to catch a breath. Their rising reputation—Illinois Lieutenant Governor Evelyn Sanguinetti spoke at the graduation ceremony last month—is opening doors. Minutes after Sanguinetti and the graduates spoke, an Illinois prison official asked if Divine Hope would consider expanding to Sheridan Correctional Center in northern Illinois.

But the logistics can be tricky. Divine Hope provides its own funding, so it isn’t affected by budget cuts, but its access depends solely on the goodwill of the administration. In addition, the class syllabus in rougher populations like ISP has to take into account days off for lockdowns, when prisoner misbehavior causes the entire population to spend the day in their cells.

Finances can also be a hardship. The inmates have to buy their own toiletries, which can lead to situations like Douglas catching catnaps while he attempts to hold down two prison jobs and go to class, or go without toothpaste and deodorant. Divine Hope professor Paul Ipema used to bring in hygiene packs for his students, but the ISP administration put an end to that last month, possibly a response to increased pressure after a recent fire killed an inmate, he said.

Working with students is rewarding, but can also be difficult and draining. When one prisoner’s mother told him she was suicidal, there was nothing he—or the Divine Hope faculty, who can’t contact the families—could do beyond pray.

And students don’t always behave the way Divine Hope wants them to. One was caught with 200 packets of peanut butter at Danville.

“So you’re saying he’s human?” Hudson asked when prison staff, who know he’s also a Divine Hope student, looked at him for an explanation. “We don’t claim to be perfect, or that once we’re done with this program we reach perfection. We all struggle.”

Indeed, Divine Hope does not turn out perfect people. Two years ago, a newly released Divine Hope student reoffended, sexually assaulting a woman before trying to set her on fire. Church members had done all they could to help him, setting up housing, getting him a job, and offering him a scholarship to go back to school.

The board and faculty were devastated, but not destroyed.

“We are praying that the victim of this crime will be restored and healed from the crime committed against her,” the board stated at the time. It continued:

We pray that appropriate justice will be done in this case. We pray for the church that is involved in the spiritual aspect of this matter. Finally, we testify that the only remedy to man’s wickedness is found through faith in Jesus Christ, as he alone provides true justice, peace, and reconciliation with God and man.

We as a board and staff remain even more committed to Divine Hope’s ministry of the gospel in the prisons and will not be deterred by any devices of Satan intended to bring disgrace upon Christ and the advance of his kingdom.

“This ministry is messy and complicated and not in the most ideal circumstances,” Ipema said. In that way, it resembles all ministry. After all, convicted felons aren’t in a special class of sinners.

“We all deal with the same heart issues,” he said. “There’s not a different gospel in prison than there is in your worship service on a Sunday morning.”

And blazing through the brokenness is hope. Ipema teaches pastoral counseling, and his students have to write a paper on how they’ve changed.

“It makes you want to weep at the brokenness,” he said. “The transformational moment for many is when they stop blaming circumstances or family or other people and start evaluating their own hearts.”

One is Anthony Robledo, who was 18 when he fired shots into a group of people. No one was killed.

“I used to wear rosaries and stuff like that, and if you would’ve asked me I would’ve said I was a spiritual person, but I probably had a gun and I probably had a couple of bags of weed in my pocket,” he told his professors. “I really didn’t understand.”

Now he does.

“It just amazes me how much God has shown me his love—you know, to be dead and now I’m alive,” he said. “It’s like Calvin said, it’s like glasses. I can see life in a clear view now.”

Involved in Women’s Ministry? Add This to Your Discipleship Tool Kit.

We need one another. Yet we don’t always know how to develop deep relationships to help us grow in the Christian life. Younger believers benefit from the guidance and wisdom of more mature saints as their faith deepens. But too often, potential mentors lack clarity and training on how to engage in discipling those they can influence.

We need one another. Yet we don’t always know how to develop deep relationships to help us grow in the Christian life. Younger believers benefit from the guidance and wisdom of more mature saints as their faith deepens. But too often, potential mentors lack clarity and training on how to engage in discipling those they can influence.

Whether you’re longing to find a spiritual mentor or hoping to serve as a guide for someone else, we have a FREE resource to encourage and equip you. In Growing Together: Taking Mentoring Beyond Small Talk and Prayer Requests, Melissa Kruger, TGC’s vice president of discipleship programming, offers encouraging lessons to guide conversations that promote spiritual growth in both the mentee and mentor.