When Cristobal Cerón was 14 years old, his parents got invited to a marriage retreat at an Anglican church near where they lived in Chile.

The Ceróns were Catholic, but only nominally, and so they went. They “got to know what Christianity was,” Cerón said. “The Anglican church served as a bridge for me toward the gospel. . . . The pastor opened the Bible in a way that I could understand it.”

Cerón’s new pastor was enthusiastic about evangelism. “I was very much influenced by him in those days,” Cerón said. “I started leading young guys in evangelism and short-term mission trips to different parts of the country.”

In 2003, Cerón and some friends led about 60 young people through a week of outreach in Santiago. They did Bible lessons together in the morning, then spread out in the afternoon to do street preaching, act out dramatic plays, and pass out tracts to people at train stations and stopped at red lights.

Cerón named it Mobilization Outreach Urbana (MOU). Over the next seven years, it expanded rapidly.

“Other churches joined us,” said Alfred Cooper, Cerón’s pastor. “People in other places wanted to do it. It began to take on national proportions.”

The growth was fast, especially in a country where less than 20 percent of the people are Protestant. By 2010, almost 2,200 young missionaries were evangelizing in 21 cities and suburbs.

“It was amazing to us,” Cerón said. “It was a miracle.”

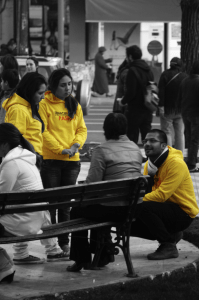

He outfitted his evangelists in conspicuous bright yellow shirts—a nod to the light of Christ—and peppered the cities with them. They’d appear on the streets for a week every July, connecting with as many people as they could.

People started to recognize the shirts and the movement. MOU was catching national, and even a little international, attention.

But the next year, Cerón almost shut it down.

“There was not much theological control,” said Sebastián Altimira, chairman of the Foundation for the Rebirth of the Passion, the organization that now houses MOU.

The theology in Chile is primarily but decreasingly Catholic—in 2014, 77 percent of adults were raised Catholic but only 64 still identified that way—combined with a swelling number of non-religious and Pentecostals. “The Anglican and Presbyterian denominations have diminished in number, and many have also departed from historic confessions of faith,” said Coalición por el Evangelio’s director of operations Steven Morales.

“You’ll find some increasing Reformed orthodoxy, particularly among Presbyterians, and some very small pockets of Anglicans and Baptists doing good work,” said Chilean Presbyterian pastor Jonathan Muñoz Vásquez.

So it isn’t surprising that prosperity theology began to creep into MOU.

In fact, more surprising was the leaders’ response. They picked up C. S. Lewis, Tim Keller, and Tom Nelson books. Then they made some significant changes.

Reformed

In 2010, almost 90 percent of Chile’s population was Christian, according to Pew Research Center. But that didn’t make evangelism passé.

A rising number of the population was religiously unaffiliated (16 percent)—about half had been raised Catholic. Of those who remained Catholic (64 percent), many were nominal. Just 8 percent of Catholics prayed daily, attended services weekly, and considered religion very important in their lives, compared to 37 percent of Protestants.

Of the 17 percent of Chileans who were Protestant, most believed a prosperity gospel. Nearly 60 percent of Chile’s Protestants—and 48 percent of its Catholics—told Pew that God grants wealth and good health to believers who have enough faith.

In this context, MOU “grew explosively,” Altimira said.

It might have gone on growing. But Cerón had spent three years at George Whitefield College in South Africa, and while he was there, “grew in understanding” of the Reformed theology his Anglican preacher had originally taught him.

He can still remember a Tim Keller sermon about “the philosophy of gospel ministry.”

“It made a huge impact on my life,” Cerón said. “It was the first time in which I came to see the gospel as the ground to understand life and ministry in a way that made sense to me.”

He was used to hearing that the gospel is the center of everything, but in a way that implied, “This is our dogma against everyone—the gospel, the gospel, the gospel.”

Keller showed him that “the gospel was not only the power to save someone from hell, but also the power to carry him to heaven.” It isn’t just “the front door to the gospel, but the narrow road to glory as well.”

So when the health-and-wealth language started creeping into MOU, Cerón recognized it.

Cutting Back

Cerón remembers a conversation with a pastor, who first alerted him that “the [MOU leaders] in some cities were thinking they were neo-prophets or neo-apostles.” Submit to these people who hear directly from God, the reasoning goes, and you will be richly blessed.

Cerón and his team were alarmed enough to make big changes. “We decided not to keep doing a thing we couldn’t handle properly.”

He didn’t stop MOU entirely, but pared it back—from 2,000 missionaries to 500, and from a dozen cities to two. He asked those involved to sign onto the Lausanne Movement’s Capetown Commitment, and he asked leaders to commit to training.

“Some legalistic evangelical leaders and some prosperity gospel churches got really angry at us, because they thought we were in a heretical movement,” Cerón said. The objectors wrote up a document and sent it to hundreds of evangelical leaders in Chile.

“The accusation was mainly about our ‘Calvinistic’ approach to evangelism and our relation to people like John Stott or Billy Graham, who they thought were heretical leaders,” he said. “It was quite a difficult time. But [the team was] united in saying, ‘If we really want to serve the church and do it properly, we have to work hard on training the next generation and putting down a solid foundation.’”

So they did.

Solid Foundation

Looking for more control and stability, Cerón set up the Foundation for the Rebirth of the Passion, and tucked MOU under its umbrella.

He also added Seedbed, which takes young Christians through two years of Bible study and book reading. They discuss Tim Keller’s The Reason for God and Galatians for You, James Sire’s The Universe Next Door, and Tom Nelson’s Work Matters. They also work through Vaughan Roberts’s God’s Big Picture and the book of Mark.

“We are preparing our own Bible studies,” Cerón said. “Those of us writing the material have been influenced by people like Miguel Nunez, John Piper, Tim Keller, Colin Marshall, and Acts 29 guys like Steve Timmis and Tim Chester. They all had a huge impact on my generation.”

For four weekends each year, the participants meet to discuss their readings and to study the Bible. One weekend focuses on basic tools for evangelism, another lays out how the gospel of Mark can be used as a tool to present the gospel, and a third gives tools for reading and teaching the Bible. Seedbed also includes a weekend on an overview of the Bible, on Galatians, on a Christian worldview, on apologetics, and on faith and work.

“After those two years, we have covered the basics of what it is to be a disciple-making disciple,” Cerón said. “Whether they go on to become a pastor or a lay person very well-trained for gospel ministry in their workplace—either way we win.”

The first class in 2012 had 25 students; the second doubled to around 50 or 60. The third class rose to 85 students in two cities. (Some graduates of that first class are enrolled in Bible college for next year and thinking about church planting.)

Seedbed leaders are careful with the growth. “It has to be done in a way that takes time and builds trust,” Cerón said. “We don’t want to commit the same mistakes we did in the past.”

Seedbed is fixing the error of theological looseness. But Cerón and his team are also repairing another problem.

Once-a-Year to Every-Day Evangelism

“At the very beginning of our [MOU] movement, we tracked a lot of numbers and even put a lot of emphasis on how many people got converted each day,” Cerón said. “I remember nights we’d come back to the main gathering place, and I’d ask them to tell their testimonies. If one guy said, ‘I had eight people praying the sinner’s prayer,’ they would all be shocked and joyful. But the guy who only had two or three then wasn’t able to open his mouth.”

That public celebration put a lot of pressure on the young evangelists.

“We pushed many times for [people] to declare with their mouths, ‘Jesus is Lord. I need the Savior. I repent of my sins and I need to be a Christian now,’” said Altimira, who was 17 when he went on his first MOU. “But as the years passed, we realized that the mission is not just the harvest. Many times the mission is to [sow the] seed.”

Now the emphasis is on depth, he said. Instead of asking young people to spend the afternoons of MOU racking up conversions, leaders ask them to find someone they could befriend.

“We say, ‘Go out and try to find somebody to be a friend to for the next 40 years of your life,’” Cerón said. “Try looking for a meaningful conversation with somebody provided by God, that you may end up with his phone number or Facebook or Instagram contact.”

That instruction “changes the character of what we were doing in the street,” Cerón said. “You don’t go for numbers. You go for people, to hear their stories and get involved with their life. That old-time anxiety I had at the beginning has vanished.”

That means fewer sinners’ prayers. But it also means more discipleship, and, perhaps, more authentic conversions when they come.

This July, about 400 MOU missionaries hit the streets, talking to people who were anxious about medical tests, worried about their home life, even suicidal. Over and over, they “established challenging friendships.”

That was exactly what Cerón wanted. And it led to another benefit.

Local Church

When you ask young people to hear someone’s story and get involved in that person’s life, you relieve the pressure of performance, Cerón said. At the same time, you’re adding pressure to the local church.

“When you’re offering a 40-year friendship, you can’t offer that by yourself,” Cerón said. “You need a congregation that will help you to be that kind of person for somebody else.”

MOU evangelists often come home “motivated” and “willing to serve their congregations in a committed and enthusiastic way,” the Foundation for the Rebirth of the Passion reported.

Sometimes the change is even more pronounced.

“[Young people come to MOU] to preach the gospel, but they find they are not really saved,” Cerón said. “They end up being converted themselves.”

Discover, Delight, Declare

From the beginning, “we had a lot of enthusiasm and passion, but we weren’t really deep,” Cerón said. “Now we are trying to bring the proper Bible teaching into every single day.”

His dream is that “the Chilean church would renew its commitment to the gospel in three areas—discovering the gospel, delighting in the gospel, and declaring the gospel.”

His dream is that ‘the Chilean church would renew its commitment to the gospel in three areas—discovering the gospel, delighting in the gospel, and declaring the gospel.’

That’s what he’s teaching the students at Seedbed, who in turn teach the students at MOU.

Altimira would love to see MOU spread up and down Chile, and out to the rest of South America. He’s dreaming about ways to get into schools—and worrying about how to staff the growing organization.

“There is so much to do,” he said.

“One day I was praying and I said, ‘God, you are the God of the mission. Why am I troubled? I don’t have to be. Go ahead and just grow us, God. This is your movement.’”