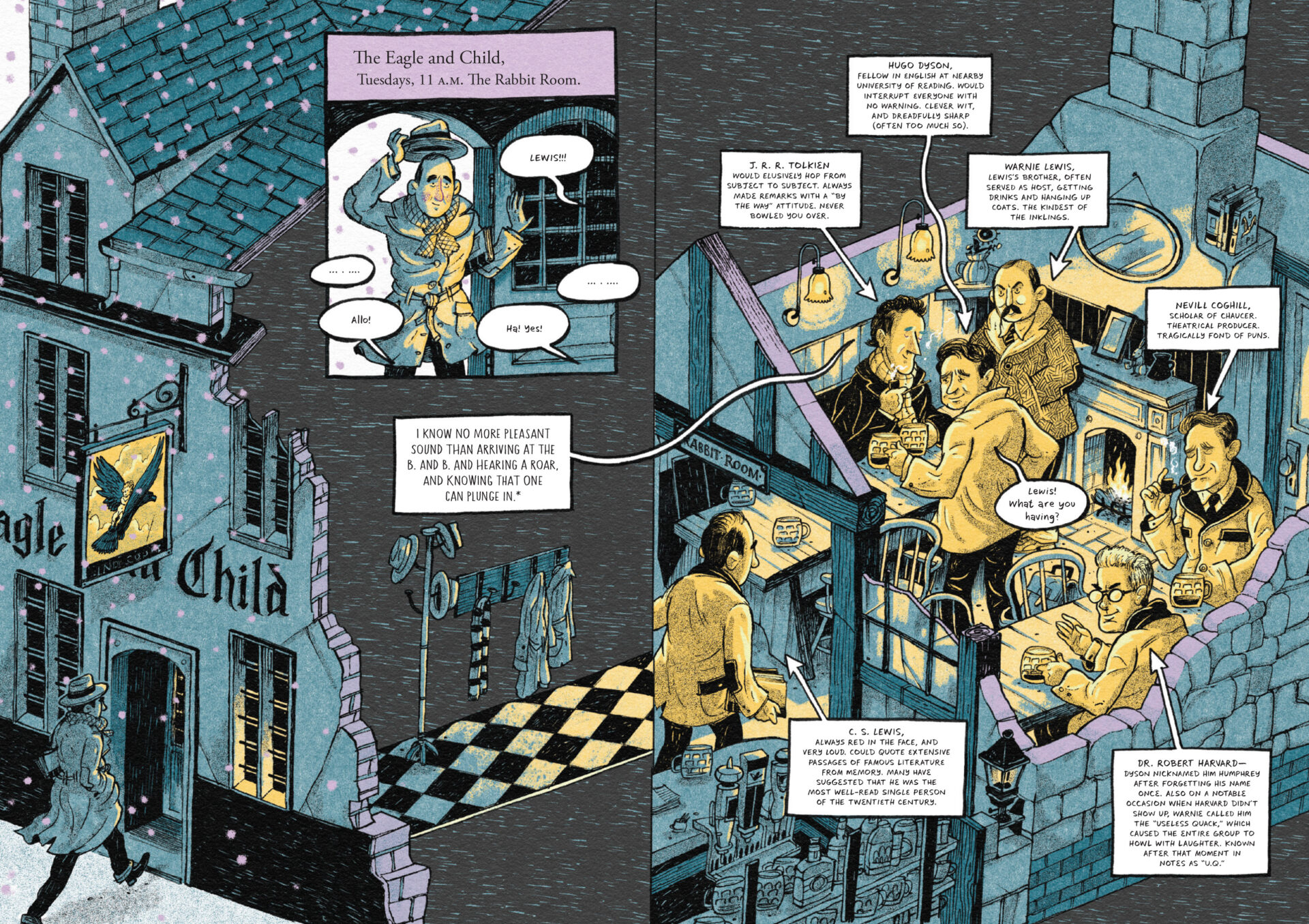

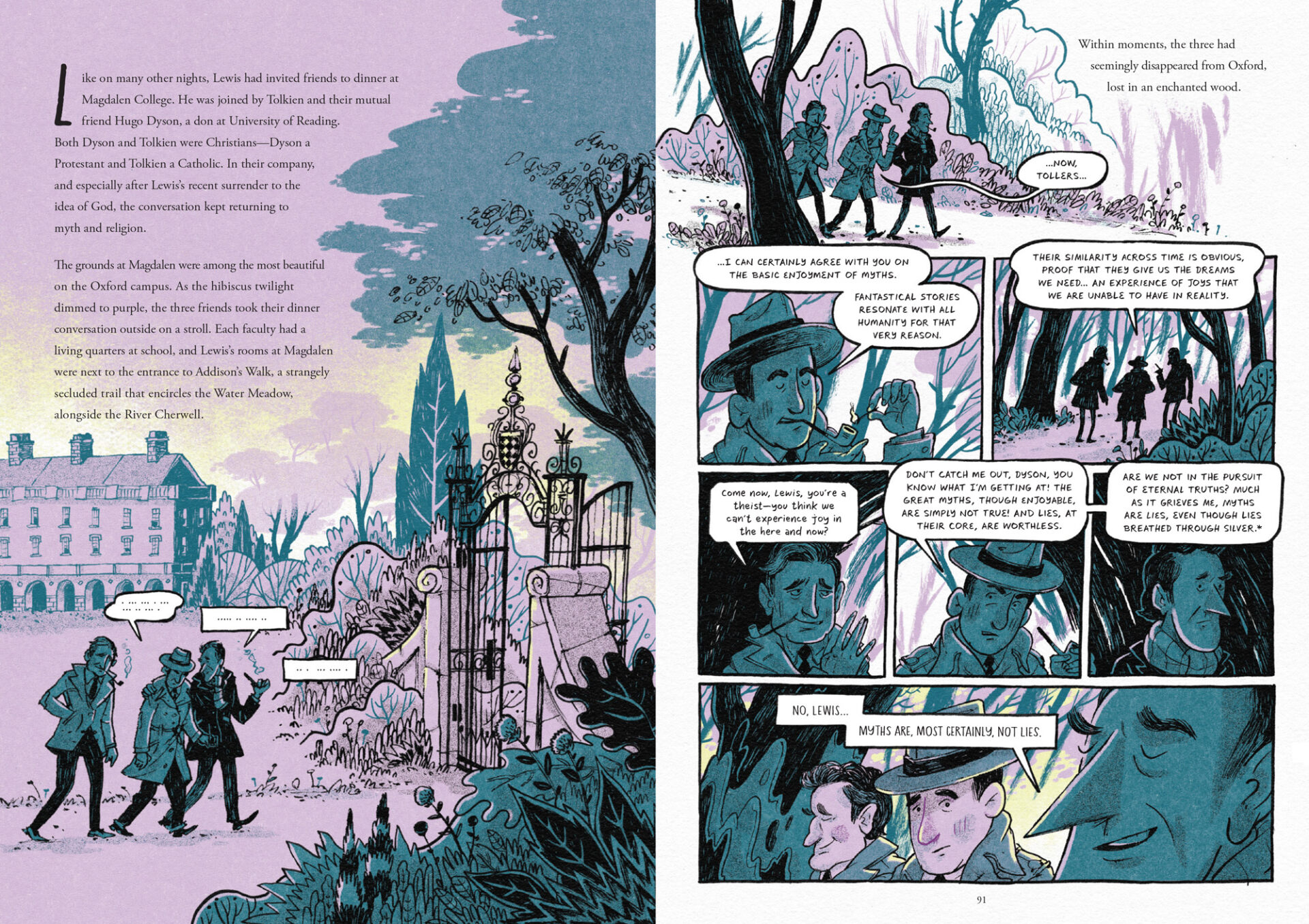

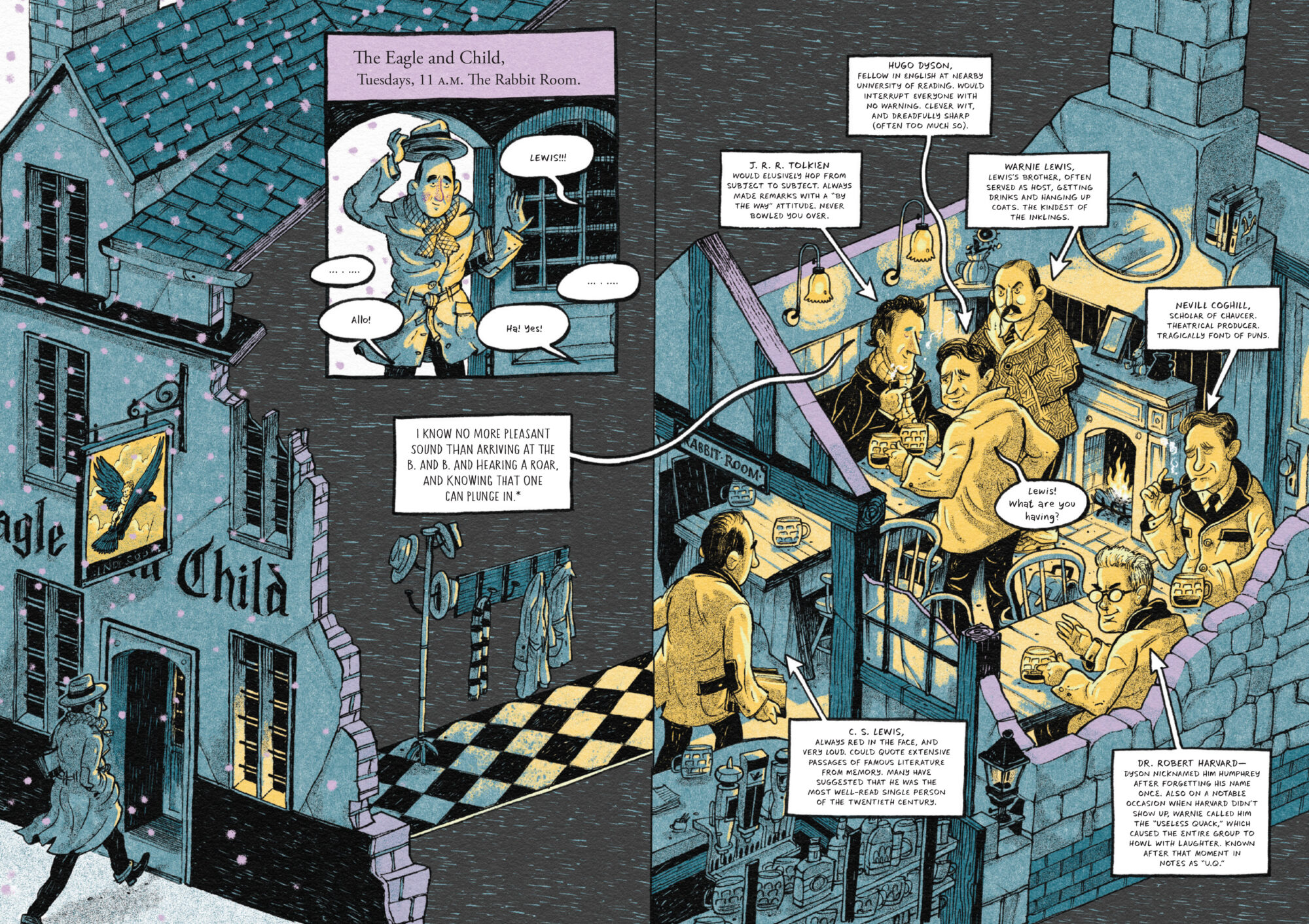

Both C. S. Lewis and J. R. R. Tolkien are towering figures of mid-20th-century literature whose legacy on pop culture—and on discourse around the “Christian imagination”—is felt powerfully today. But neither author would’ve become who he was without the influence of the other. Their decades-long friendship unfolded in college rooms, pubs, and garden paths in Oxford—but its ripple effects have been felt around the world, for over half a century. On one level, these were just two tweedy blokes who geeked out over Norse mythology while sipping pints at The Eagle and Child. But history has shown their friendship was hugely consequential for the faith, art-making, and amusement of scores worldwide.

Lewis and Tolkien’s decades-long friendship unfolded in college rooms, pubs, and garden paths in Oxford—but its ripple effects have been felt around the world, for over a half century.

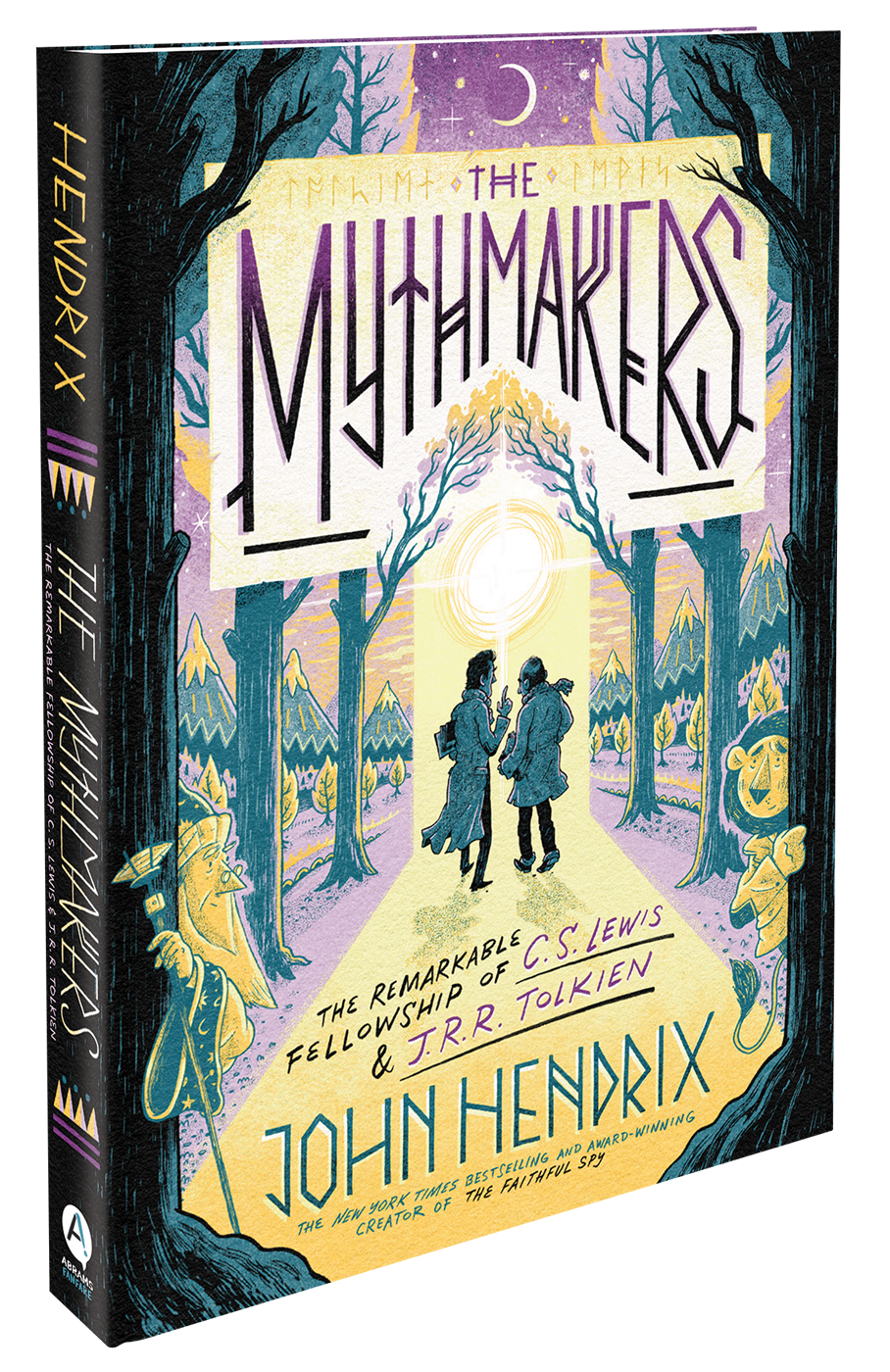

The Lewis-Tolkien relationship has been told in many books before, but never like it is in The Mythmakers, a just-released graphic novel by the acclaimed illustrator John Hendrix (who’s a believer). Geared toward young-adult audiences but rewarding for older readers too, The Mythmakers combines artistic whimsy, theological reflection, and flourishes of Sehnsucht in a way that feels totally appropriate for a book on the Lewis-Tolkien story. In a real sense, the medium is the message of this book. I highly recommend it to anyone with an interest in the Inklings or a general desire to think more Christianly about art and the creative community.

I recently chatted with Hendrix about his inspiration and process for The Mythmakers, what most surprised him in the research, and what the church can learn about Christian art-making from Lewis and Tolkien.

Where did you first get inspired to tell Lewis and Tolkien’s friendship story?

What most people need to know about this book is that it’s basically fan art. At the core, I just owe so much to these two men and their works, and the permission it gave me as a young person to not just take my imagination seriously, but also my faith really seriously too. The book is about an exploration of their dual biography, but it’s using their friendship story as a lens to ask some larger questions about storytelling and fairy and the history of myth in general.

Do you remember how old you were when you first encountered Lewis and Tolkien?

For both of them, I have very vivid young memories. Someone gave me an illustrated copy of The Hobbit. It had a very vivid drawing of Smaug on the cover, and I carried it around, even after I had finished the book, like it was a Bible. I would travel with it, and it was very important to me, the illustrations particularly.

Then I read Narnia. I think I had even read them out of order initially. I did not really clock the allegory, at least in terms of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe. They were just great stories—portal fantasy to me. Then later, I’m like, “OK, I see what he’s doing there.”

What did the research look like? Was it hard to get to a point where you felt comfortable telling the story with accuracy and fidelity to what actually transpired?

It is such an act of humility to try this at all. David French said this thing recently, and I’ve been thinking about it: humility should be indexed to complexity. The more complex something gets, the more humble your mindset should be. And this is what happens anytime I learn about anything. I think I know the most at the beginning, and then the more I read—somehow—the less I feel like I know.

I read a lot of books. I went to Oxford. I drew all night at The Kilns, and I tried to just load my brain up with as much as possible. But, for me, the real act is stepping away and asking, “What is the metatext? What is the metanarrative?” And then finding ways to cite that idea throughout the book in a form that a Young Adult (YA) audience can really understand and maybe internalize. That’s the goal for me.

Do you illustrate simultaneously with the research, or do you research on the front end before you even illustrate? How does that process work for you?

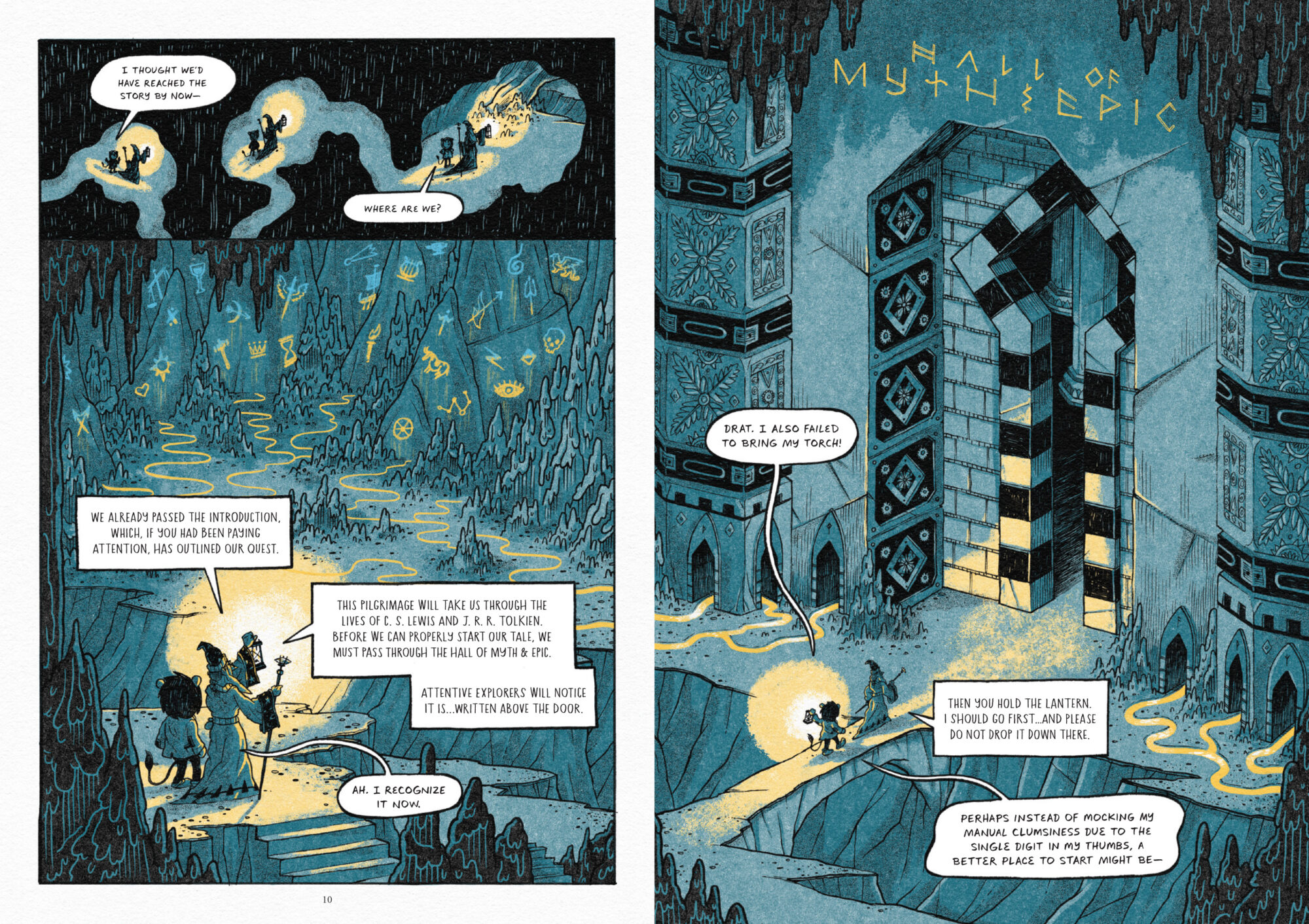

I start the book with images that I really want to make, and then I write a little bit. And then writing is honestly so abstract for me that it is really hard for me to write without the imagery alongside it. The framing device in this book of a lion and wizard came along because I’m making a graphic novel about the Inklings, and most of what they do is sit around and talk. You can’t have 300 pages of that. I needed a narrative frame that allowed us to go on some of the adventures, and that allowed young readers to latch on to these ideas. The lion and wizard framing developed very early on out of a drawing, and that gave me a place to write from.

I’m making a graphic novel about the Inklings, and most of what they do is sit around and talk. You can’t have 300 pages of that.

For Tolkien, I considered maybe king or elf, but wizard seemed to fit his personality too. And lion fits Lewis so well, because he was such a boisterous, big personality. I have to test everything out, and in this case, when I started writing with that framing, it worked. It was one of those things where I’m like, “Oh, this is happening.” And then it was a matter of convincing my editor this was the right choice.

Was there anything in the research about Lewis and Tolkien that came as a surprise to you?

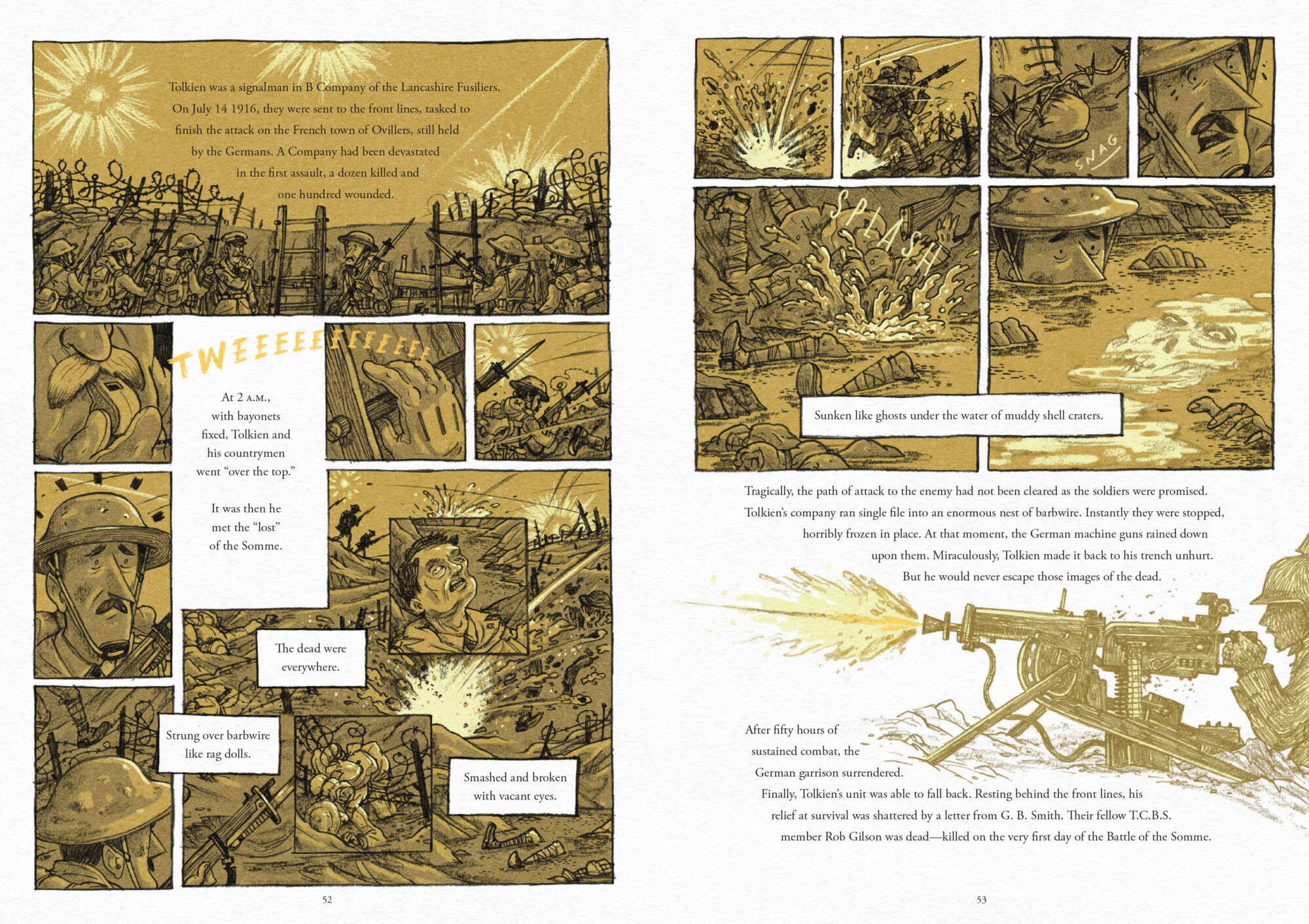

I had known the basic beats of their story together. But I think the depth of their estrangement and the pain they felt from that was really heavy. I really remember thinking, What does this do to this story? And ultimately, I realized it was so necessary to tell the tale. In some ways, it made it more poignant, and it pointed toward the ending of the story, where I give them a chance to recapitulate the losses we all feel on this earth before we enter the new creation.

I’ve heard from several readers who had to put the book down when they got to that because it was such a bummer, but I do think it offers us lessons about friendship and fellowship and creative community. Consider any friendship you’ve had in the last 30 years. We all change. How do you support one another as you change? How do you not grow bitter or jealous—or the thing that happens in old age where your ideas start to calcify and you’re less flexible?

The book is about how important relationships are for forming our creative imagination and process. So I’m curious about you as a creator: What does this look like for you? Do you have any long-term relationships with fellow creatives who really spur you on?

I tell my students that our work always gets better in community. And for some reason the world tends to tell artists the opposite, right? The book is dedicated to two of my friends at Washington University: Abram Van Engen and John Inazu—both professors and people that I trust—that have now been in my life for over 10 years, and I hope are here long after that time. To have a collaborative community—especially people who share your faith and share your aims for what your work can do in the world—is so valuable.

All three of us had books come out this year, and I was able to illustrate both Abram’s and Inazu’s books. It was a really sweet celebration of collaborative and shared mission. I don’t think everyone has that, and maybe not everyone has it for every season of their life, because I certainly couldn’t have said that 15 years ago. But when we come into these moments of creative community and collaboration, it’s really wonderful.

A half century later, we’re still pointing to Lewis and Tolkien as some of the best examples of Christian art-making. What can Christian institutions, churches, and communities do to create fertile soil for the next Lewis or Tolkien to emerge? What can we do better as the church to inspire creative excellence?

It’s such a good question. First, you have to have the desire for artists to participate in that storytelling. If you had told me when I was 18 that I would be making a literal picture book about Jesus, that would have struck me as “Surely that cannot be good.” Because what I saw in Christian bookstores was uninteresting kitsch. It’s not that it was bad. It was boring.

The church should try to support things that are weird. We should try to relax our reflex for fear. Maybe churches could regularly give out studio spaces for artists and not police what goes on there—maybe just invite in people from the community. This could be a way for the church to become a vessel where people see the church as wanting interesting things to be made, as opposed to “Let’s have you sign this faith statement before we let you make some canvases in our basement.” There needs to be discernment, sure. But in general, fear has tended to run the show.

Do you think there’s anything in Tolkien’s idea of sub-creation that Protestants can learn from?

Protestants threw out all the art in the cathedrals. I get why we did that, but we are honestly still dealing with the repercussions. Lewis and Tolkien are these perfect little avatars for their little Protestant-Catholic differences. Tolkien’s world is adorned with baroque things. There are things everywhere, and he made them for the goodness of making. But I think you could actually argue that The Lord of the Rings’ Middle-earth is almost more infused with gospel ideas than Narnia, if you had to truly count them up. Protestants should be OK with the idea of myth being something that points to the deepest, truest things. We are telling certain stories over and over again for a reason, and there is a certain mystery there.

For a young person who’s a Christian and cares about the arts, and maybe has artistic ambition, what do you hope he or she takes away from The Mythmakers, especially regarding creativity and faith?

My favorite thing inside of this research was reading some of Tolkien’s letters. It’s the thing I tell people to read if they want to really digest something of his they haven’t encountered yet. One thing that’s clear from the letters is that great art is made on a Tuesday afternoon. We look back at them as these geniuses, but they did not know they were the C. S. Lewis and the J. R. R. Tolkien. They were two guys who were meeting in between curriculum committees.

There’s this one passage I cited in the author’s note where Tolkien talks about how in the morning, he took Frodo and Sam to the gates of Mordor. In the afternoon, he cleaned the chicken coops and worked on the plumbing. He was Tolkien, but he was plumbing his own toilet. The thing he wants to do is write The Lord of the Rings, but he’s got life happening around him. Lewis and Tolkien were just extremely normal people who were not corrupted by fame or the sort of genius-tag that happens in our world today.

So for young people reading this: Make your art. Be faithful to it. Find friends who can share the journey with you, and enjoy the act of creating. Tolkien’s whole idea was sub-creating. We honor God when we create like him, and that’s such a beautiful idea.