In 1721 a vicious virus struck Boston. The variola virus—more commonly called smallpox—wasn’t novel. The earliest written descriptions of it came from China in the fourth century. The fatality rate from smallpox was about 30 percent (for comparison, the fatality rate of COVID-19 is around 5.7 percent, according to the CDC.

Smallpox was a beast.

The conquest of smallpox began when two Puritan pastors investigated whether God had provided a solution for the virus in nature. So, in the face of the outbreak, some Puritans began experimenting with inoculations—experiments that provoked fierce opposition.

Puritan Pastors and Variolation

Puritan ministers like Cotton Mather (1663–1728) and Benjamin Colman (1673–1747) were among the leading figures in New England society. Mather was the son and grandson of Puritan founding fathers; Colman the influential founding pastor of Boston’s Brattle Street Church. Having lost 10 children, Mather was no doubt desperate, and he channeled his quest to save his children from the disease in a way that may surprise those who dismiss the Puritans as legalists and religious escapists.

Mather had learned of inoculation from his African slave, Onesimus, whose people, the Guramantese, practiced it. The slave’s account, with a scar to prove he had survived it, was confirmed by reports from Turkey.

Mather’s first guinea pig would be his own son, Samuel.

Mather took some blood and pus from a person with a mild case of smallpox and gave it to Samuel—a procedure called “variolation.” Samuel came down with a mild case but soon recovered. Soon, many were willing to have Mather inoculate them; others were horrified, though, and he suffered severe harassment. One man threw a bomb into Mather’s house with a note attached: “This will inoculate you, Cotton Mather.” The bomb was a dud.

James Franklin (1697–1735), older brother of Benjamin Franklin, started a newspaper with a stated mission of denouncing Mather’s “morbid” experiments. The Massachusetts House of Representatives passed a bill outlawing inoculations—but it stalled in the upper house. Where were the doctors in all this? Surprisingly, most physicians stood with the mob, James Franklin, and the legislators.

Writing for most other Boston doctors, John Williams published “Several Arguments Proving that Inoculating the Small Pox is not contained in the Law of Physick, Either Natural or Divine, and is therefore Unlawful.” In it he argued, “Inoculation is a doing violence unto the law of nature and the pattern which God has set us. . . . Therefore, inoculation is unholy.”

The 1721 Boston smallpox epidemic saw most physicians opposed to inoculation, while many ministers supported it. Cotton and his father, Increase Mather, were joined by Colman and his associate, William Cooper, in openly supporting inoculations.

Science and Religion

What was it about Puritanism that equipped its ministers to be so open to scientific advance even in the face of widespread opposition?

People today are looking to science for salvation from the coronavirus. There’s a modern, secular myth that says Christians have historically opposed science. The official CDC account of the discovery of the smallpox inoculation attributes it to an English physician, Edward Jenner (1749–1823), without mention of the pioneering work of the Puritan pastors two generations earlier.

Truth is, Puritanism championed science precisely because of its core theological convictions. Rather than dissenter-burning, otherworldly, closed-minded tyrants many imagine them to be, the Puritans were, as I’ve defined them elsewhere, “an inner-worldly ascetic evangelical movement aimed at holistic social transformation according to the ideational pattern of Scripture and beginning with the personally experienced regeneration of sinful human beings.”

Inner-worldliness and holism are particularly relevant here.

For example, Colman and Cooper published a tract in favor of the inoculation experiments that opened an intriguing vista into the Puritan worldview. A common criticism of inoculations was that they were “taking God’s work out of his hand.” The few Christians who today eschew modern medicine make much the same argument. Cooper, in words Colman echoed the next year, agreed that smallpox (“the distemper”) can “arrest none without a commission from God.” However, he knew it spreads “by means of second causes.” Whether caught by infection or inoculation, it’s still the work of God—for all secondary causes depend on and act under him, the first cause.

Some argued God has predetermined how long we are to live and that inoculation attempts to alter God’s decree. Colman and Cooper, in “A Letter from a Friend in the Country,” agreed with the premise but denied the conclusion: “He that has fixed his own counsel how long we shall live, has also determined that by such and such means our lives shall be continued to that period of time.”

The Creator of nature is no “God of the gaps.” God has created means—cause and effect in the natural world—so we might discover those means and use them.

God’s Two Books

The Puritans believed the book of nature agrees with the book of revelation, the Bible. Creation is God’s other book, besides Scripture, and it too is worth intensive study. Increase Mather articulated this doctrine succinctly: “The [natural] works of God have a voice in them, as well as his Word.” He was one of the first to write a book on comets. Mather observed comets with the telescope brought to Harvard in 1663 by a young scientist from the Royal Society (a scientific organization founded mostly by Puritans that gave us Isaac Newton) named John Winthrop Jr. (1606–1676).

Winthrop was the son of the founding governor of the Puritan “Bible Commonwealth” of Massachusetts and was himself a long-serving governor of equally Puritan Connecticut. He was also one of the most distinguished New England scientists. The Royal Society named him a member and published some of his observations of animals and fauna.

Cotton Mather was a Royal Society member and should be considered a scientist too, precisely because he was a Puritan minister. Besides experimenting with smallpox inoculations, he studied “little eels” (micro-organisms) through his microscope and Halley’s comet through the Harvard telescope. He viewed such scientific observation as “acts of devotion themselves, giving new grounds for praising the Almighty by enhancing his sense of the perfect order of things.”

Their commitment to science was such that the late-stage Puritan Jonathan Edwards was inoculated against smallpox in 1758 with tragic results. The inoculation killed Edwards five weeks after his inauguration as president of the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University).

The Puritans never dreamed biblical truth should be embraced despite the evidences of reason or science. The Copernican theory gained early acceptance in New England. The unity of all truth, both revealed and empirical, was a basic Puritan conviction. As Puritan scholar Perry Miller observes, “Puritanism looked upon itself as the synthesis of piety and reason.”

This synthesis is a large part of what made Puritanism a potent force in shaping emerging modernization.

Theology and Science Are Friends

Because scientific progress, we are relatively free from uncontrollable terrors such as Cotton Mather faced, even if we are getting a taste of it with COVID-19.

Theology for the Puritans was not an escape from the realities of this world, but an impetus to study and harness God’s world. Nobel laureate Simon Kuznets notes that a growing control over the environment—especially over catastrophic pandemics—is one of the marks of modernization.

Today we associate this movement toward control over nature with science, which many, in turn, associate with secularization. Yet the Puritans, in their unstoppable urge to hear God speaking in creation as well as in his Word, were pioneers of this movement. They show us how science and theology can be friends, the very means employed by God to bring holistic healing to body and spirit.

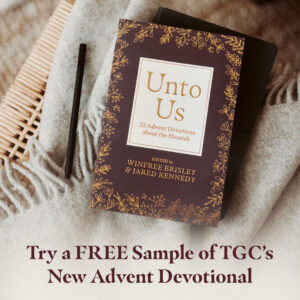

Try Before You Buy: FREE Sample of TGC’s New Advent Devotional

Choosing the right Advent daily devotional can be tough when there are so many options. We want to make it easier for you by giving you a FREE sample of TGC’s brand-new Advent devotional today.

Choosing the right Advent daily devotional can be tough when there are so many options. We want to make it easier for you by giving you a FREE sample of TGC’s brand-new Advent devotional today.

Unto Us is designed to help you ponder the many meanings of this season. Written by TGC staff, it offers daily Scripture readings, reflections, and questions to ponder. We’ll send you a free sample of the first five days so you can try it out before purchasing it for yourself or your church.