I first saw this photo a few years ago. Since then, I think of the men in it every May 4.

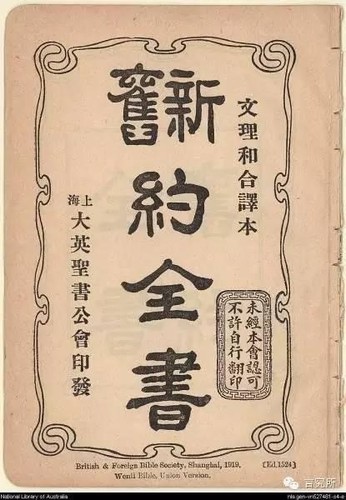

Those pictured helped translate and revise a book printed on April 22, 1919, in Shanghai, just days before the beginning of the May Fourth Movement. Those translators’ work, like the May Fourth Movement, had a profound effect on the Chinese and their history. Still, the book remains mostly unknown in China, though many have heard of it.

Even less familiar to the public are those in the photo. Of course, these men probably didn’t care whether future generations would remember them. They valued the book itself and the effect it would have on the people of China.

Yet these men deserve to be remembered, for the book they translated was the Mandarin Union Version, Old and New Testaments. Today, the most prevalent Chinese Bible is based on this translation.

Laying a Foundation

According to the references accompanying the photo, the men pictured are, from left to right: 鲍康宁 Kangning Bao (Frederick William Baller, 1852–1922), 刘大成 Dacheng Liu, 富善 Shan Fu (Chauncey Goodrich, 1836–1925), 张洗心 Xixin Zhang, 狄考文Kaowen Di (Calvin Wilson Mateer, 1836–1908), 王元德 Yuande Wang, 鹿依士 Yishi Lu (Spencer Lewis , 1854–1939), 李春蕃 Chunfan Li.

The historical documents offer no exact birth and death records for those who only had a Chinese name.

Dacheng Liu was a mainland Chinese collaborator with the British-born missionary Frederick W. Baller. Xixin Zhang taught and collaborated with the American Congregational missionary Chauncey Goodrich. Yuande Wang studied and collaborated with the U.S. Northern Presbyterian missionary Calvin Wilson Mateer. Chunfan Li collaborated with the American Episcopal missionary Spencer Lewis.

Little-Known Heroes

The first time I saw a Bible was in my home. I was in elementary school, and it wasn’t called the Bible. I later found out my mother had bought it from a local southern suburban church. At that time, it felt like an ancient Chinese book. Not only was it written in traditional Chinese characters and read from top to bottom and right to left, but the font and style of the title page was also nearly the same as in the original Mandarin Union Version.

Even more people were involved in the translation and revision work for the Bible I first saw as a child. Western missionary contributors included: 白汉理 Hanli Bai (Henry Blodget, 1825–1903), 文书田 Shutian Wen (George Owen), 倪维思 Weisi Ni (John Livingston Nevius, 1829–1893), 布蓝非 Lanfei Bu (Thomas Bramfitt, 1850–1923), 海格思 Gesi Hai (John Reside Hykes, 1952– 1921), 赛兆祥 Zhaoxiang Sai (Absalom Sydenstricker, 1852–1931, writer Pearl Buck’s father), 安德文 Dewen An (Edwin Edgerton Aiken, 1859–1951), 林辅华 Fuhua Lin (Charles Wilfrid Allan), 克拉克 Lake Ke (Samuel R. Clarke), 林亨理 Hengli Lin (Henry M. Woods), 路崇德 Chongde Lu (James W. Lowrie), 瑞思义 Siyi Rui (William Hopkyn Rees, 1859–1924).

There were also at least two other Chinese contributors: 诚静怡 Jingyi Cheng (1881–1939), a coworker of the English London Missionary Society missionary George Owen, and 邹立文 Liwen Zou, a student of Mateer’s.

These names aren’t found in most modern Chinese historical records. If one digs a little deeper, however, a close link can be found between these people and the formation of modern China. They helped open the era of modern Chinese history even earlier than those who initiated the May Fourth Movement.

Translating Eternity

For some, shaping modern China was a byproduct of their being sent to China. They were more concerned about translating and revising the Bible, which describes how eternity entered into our temporal world. These men valued the knowledge they brought from the West to help improve the life of the Chinese people. Ultimately, they helped Chinese people learn how to enter the eternal realm—Christ’s kingdom.

The initiators of the May Fourth Movement and those who followed focused on the survival of the temporal realm. To many who know modern Chinese history, this is understandable. This focus was also common among many Western missionaries and the Chinese people. The gap in many aspects of daily life between China and the West, along with the conflicts generated once the West forced its way into China, created a sense of urgency among many to seek eternal things.

It’s difficult for humanity to transcend time. Perhaps they didn’t expect to establish the eternal realm in a temporal world, but the book these men helped translate transcends time and changes lives.

Editors’ note: Would you join us in resourcing thousands of church leaders in China with gospel-centered resources? All gifts to our Chinese Outreach will be matched (up to $40,000). Learn more about this exciting Theological Famine Relief opportunity.

Previously:

- Send Gospel Resources to China (Bill Walsh)

- Chinese Christians Preparing for ‘New Normal’ (Andrew Kaiser)

- What Christianity in China Is Really Like (Colin Clark)

- The Church in China at the Threshold (Brent Fulton)

- The Bells in China Are Not Silent (Joann Pittman)

- Young, Restless, and Reformed in China (Sarah Zylstra)

A version of this article appeared at ChinaSource. It was originally posted to the WeChat public account The Word Institute.

Try Before You Buy: FREE Sample of TGC’s New Advent Devotional

Choosing the right Advent daily devotional can be tough when there are so many options. We want to make it easier for you by giving you a FREE sample of TGC’s brand-new Advent devotional today.

Choosing the right Advent daily devotional can be tough when there are so many options. We want to make it easier for you by giving you a FREE sample of TGC’s brand-new Advent devotional today.

Unto Us is designed to help you ponder the many meanings of this season. Written by TGC staff, it offers daily Scripture readings, reflections, and questions to ponder. We’ll send you a free sample of the first five days so you can try it out before purchasing it for yourself or your church.