About 10 years ago, a couple of pastors broke into one of Boston’s most famous churches.

“It’s 8:00 p.m. and we’re walking by Tremont Temple,” said pastor Curtis Cook. “The lights are off. The doors are closed. And Mark’s like, ‘Can we go in?’”

“Mark” is Mark Dever, pastor of Capitol Hill Baptist Church (CHBC). He and a friend were having dinner with Cook when the conversation turned to Tremont Temple Baptist Church.

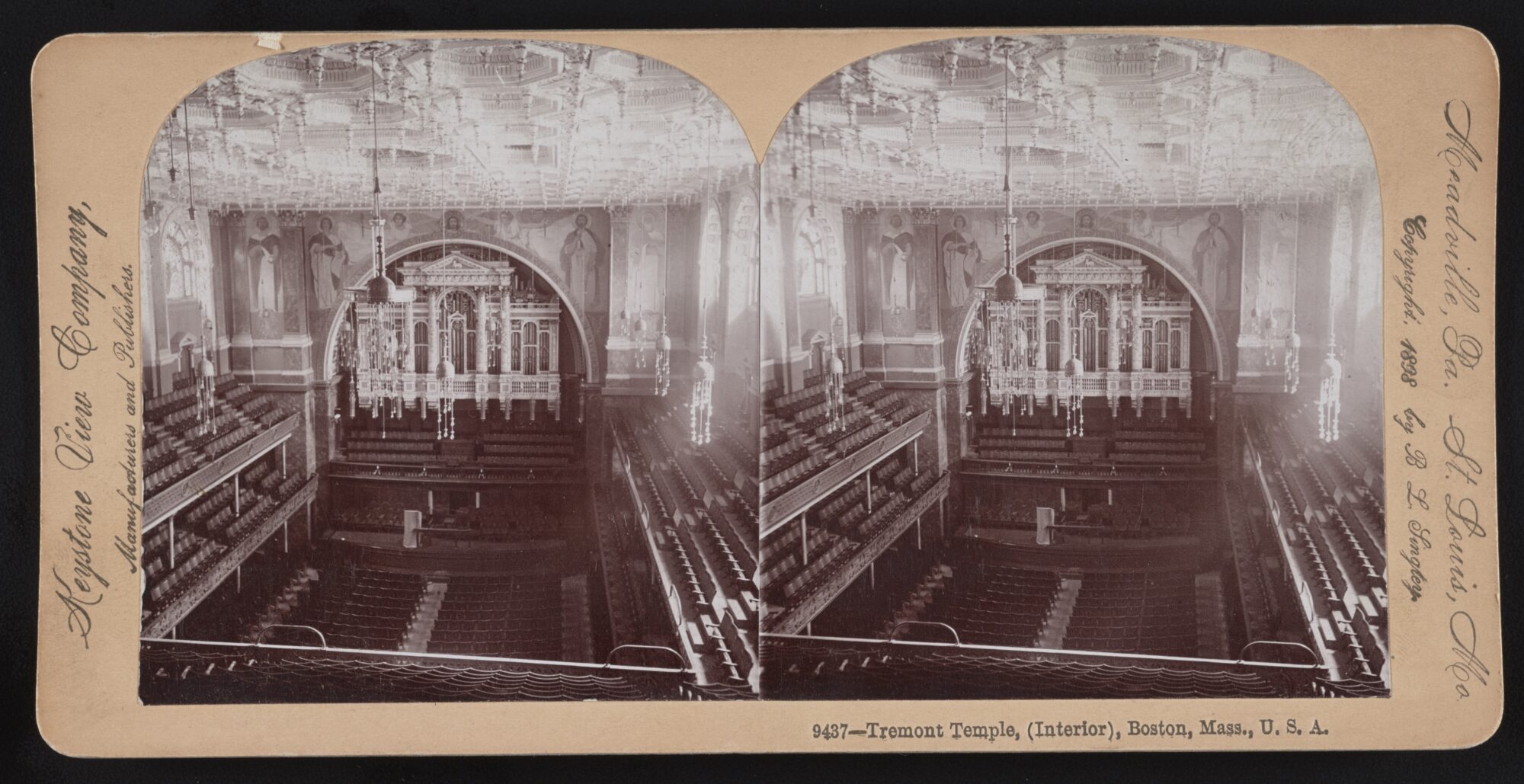

Tremont Temple is massive, in both size and history. The 186-year-old church seats nearly 2,600 in a gorgeous, ornate building. One of the first churches in America to be racially integrated with free black members, it has hosted speakers such as Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass. By 1929, its diverse congregation of nearly 4,000 members had a vibrant Sunday school, choir, Bible class, baseball team, and bowling league.

But nearly a century later, attendance at Tremont Temple had shrunk to around 70 on a good week. The preaching wasn’t expositional. Financially, it was failing.

“It costs about $20,000 a month to keep the building going,” said longtime member Phyllis DaRocha, who was on the finance committee. “Utility bills alone are in the thousands. Nothing is cheap, and that’s not counting insurance or salaries.”

Area pastors worried about its slide. Across New England—the least religious area of the country—church buildings are being turned into restaurants, bars, and condos.

“We were afraid the gospel would no longer be preached there,” Cook said. He and Dever tried a few doors until they found one unlocked.

“We go walking in the church,” Cook said. “We found our way into the sanctuary, and we prayed for God to provide a way forward.”

It’s been about a decade. These days, a former CHBC intern named Jaime Owens is the lead pastor of Tremont Temple. He preaches expositionally to about 100 to 120 weekly attendees. They have small groups, a plurality of elders, and 15 men learning to preach.

And they’re financially solvent.

“It has to be God’s miracle,” said DaRocha. “Our church is flourishing.”

“It’s exciting, because you can see God’s hand working in how he makes these things happen,” said Norman Crump, who has been a member since 1995. “We are blessed that God has given us a good building to be in. But the richness of the teaching surpasses the richness of the building.”

Tremont Theatre

Back in 1838, an ardent abolitionist and deacon named Timothy Gilbert grew irritated that his church, Charles Street Baptist in Boston, barred black people from sitting in the main sanctuary. So one Sunday, Gilbert brought a black friend to his pew. When that inevitably sparked a fight with church leaders, Gilbert left and started a congregation pointedly called the Free Baptist Church.

Within three years, the Free Church had 325 members. The next year, they baptized 138 more, perhaps in part because revivalist Jacob Knapp was in town. He preached passionately against sin, including slavery, rum, and theaters, and was so effective that for a while nearly every theater in Boston was forced to close.

For the financially struggling theater on Tremont Street, that was the end. The bankrupt theater was forced to sell its building—to the Free Church Baptists.

The Baptists, who renamed themselves after Tremont Street, spent the next 60 years in one adrenaline rush after another: Since their building was one of the biggest in town, it was where Abraham Lincoln gave a speech in 1848. In 1850, it was where an Egyptian mummy went on display. Over the years, a string of famous speakers stood on Tremont Temple’s stage—Frederick Douglass, Daniel Webster, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Harriet Beecher Stowe, and D. L. Moody. In 1867, Charles Dickens read from The Christmas Carol at Tremont Temple.

The whole time, the congregation—and the city—was thriving. From 1850 to 1900, Boston’s population boomed from 200,000 to over a million. Tremont Temple’s membership—still racially diverse—grew to more than 2,000.

But it wasn’t all easy sailing.

Fire!

In 1852, Tremont Temple caught on fire and had to be rebuilt. In 1879, the church caught fire again. And then again in 1893.

“This last calamity led to many very serious questions,” wrote George Lorimer, who was then the pastor. “The new fire laws demanded a great increase in the outlay for reconstruction. We could not build cheaply, if we would, and it was at first thought probable it might be best to abandon the location.”

The congregation could get enough money from selling the land to buy something in the suburbs, Lorimer said. “But the members could not tolerate the idea of abandoning a position so strategic, surrendering the hold that Protestantism has through this organization upon the heart of the city.”

So instead of leaning out, the people leaned in, building a seven-story church “commensurate with the value of the ground and one that would afford increased facilities to the work of the church,” Lorimer said.

He wasn’t kidding. The last rebuilding, in 1896, was probably the most ornate ever constructed by a Baptist congregation. From the steel frame to the mechanical works to the paint on the woodwork, the materials were fireproof. Double-paned glass windows kept the sanctuary quiet from noise on the street. Two thousand light bulbs were powered by an electrical generator. The outside facade included 10,000 bricks placed in a carefully considered pattern—“like a huge mosaic,” Tremont Temple’s famed architect said.

The cost was substantial—$523,000 back then, which would be around $20 million today. Lorimer did some fundraising, but overall, he wasn’t too worried about it. He planned to rent an entire floor to the Missionary Union at a low cost, which would benefit both the missionaries and the church. Add a few more floors of offices and some ground-level storefronts, and the building could bring in enough rent money to easily take care of the debt.

He was right. In fact, by showing “wholesome” movies—think David Copperfield and the Wizard of Oz—from 1908 to 1926, Tremont Temple not only paid off the building but bought a new organ.

By 1929, things were going like gangbusters. The country was prosperous, Boston was booming, and Tremont Temple had close to 4,000 members. Their pastors were theologically orthodox. Their outreach was drawing in new converts. And the congregation was caring for their new building by setting up endowments for things like altar flowers, the pastor’s carriage, and radio programming.

What could go wrong?

What Went Wrong

First, the stock market crashed the economy. Then manufacturing declined or moved away. Unemployment and poverty rose. Families moved to the suburbs for better education and less crime.

Between 1950 and 1980, Boston lost almost 30 percent of its population.

Tremont Temple’s population dropped right along with Boston’s. By the late 1940s, her membership was down to 2,000. By the 1950s, the storefronts on her ground floors had been abandoned. By the 1980s, the leaders were asking the city for permission to build a 37-story tower for offices and hotel rooms, along with a multilevel garage, so they could gain enough funds to repair their building. But this project, and another later proposal, fell through. By 2007, Tremont Temple’s attendance slid under 200.

Tremont Temple’s denomination—the American Baptist Churches USA—was also struggling. Egalitarian since the 1800s, the denomination affirmed that homosexuality was incompatible with Christian teaching in 1992, but the next year said there are “a variety of understandings throughout our denomination on issues of human sexuality.” Both sexuality and abortion issues were left to the discretion of the local churches, where membership fell from around 1.6 million in 1982 to 1.1 million today.

That’s the church Owens stepped into in 2015 when he took a call to Tremont Temple. The church had a female associate pastor, a firm stand on biblical sexuality, and about 70 aging weekly worshipers in a crumbling building with more and more deferred maintenance.

The pastor before Owens, Denton Lotz, had an assessment done. Longtime member Jane Crump remembers what it said: “We were almost dead.”

Almost Dead

Initially, Owens was hired as an associate pastor. When Lotz retired, 31-year-old Owens was a natural candidate.

“People were skeptical because he was a kid,” Jane Crump said. “But he was such a good preacher, and a good man who loved the Lord.”

Tremont Temple promoted him, and Owens got to work. He had coffee with everybody, preached expository messages, and hired an associate pastor, Dave Comeau. Together they worked on introducing a plurality of elders, tweaking the church’s bylaws, ending some programs, and restructuring adult Sunday school classes. They explained the concept of congregationalism, started dreaming about evangelism, and hung banners proclaiming “Christ Is All” on Tremont Street.

In 2019, they went through the finances.

“We do have a trust—actually, several trusts,” DaRocha said. “But they are supposed to be there for emergencies.”

Not only that, but some of those funds are restricted—they can only legally be used for their intended purpose, such as funding an orchestra for the Christmas concert.

Over the years, shrinking membership meant money for regular operating expenses had to be taken from the trusts—sometimes from the wrong accounts. Slowly, Tremont Temple’s normal expenses were draining its emergency reserves.

Meanwhile, the church needed a $600,000 sprinkler system, the elevators were broken, and the balcony outside was about to collapse onto passersby.

Immediately, Tremont Temple’s leaders tightened things up. The Christmas concert was canceled. Owens took a pay cut. Comeau moved to another area church to become a church-planting resident. Two janitors and the secretary were laid off.

“We were having to decide which staff to let go,” DaRocha said. “It was terrible. It was a really hard time for the church. . . . We realized that if we couldn’t turn this around, we might end up losing the building. People were shocked and heartbroken.”

One was Sara Colum, who’d been attending for about 15 years.

“I always thought of the building as just beautiful,” she said. “It’s something we treasure, something that feels like home. I was really torn up about the idea that we might have to sell and be a church somewhere else.”

Part of it was the history—for more than 180 years, Christians had gathered there to hear God’s Word, sing, and evangelize.

And part of it was location—Tremont Temple sits in the heart of downtown Boston.

“What that means is, if we had to sell the building, it’s a gut-job, if not a total teardown,” Colum said. She’d seen other churches in the area turned into condos, restaurants, and a Dollar Tree store.

Thinking of Tremont Temple as upscale apartments or a nightclub made the congregants feel a little sick.

“It’s spiritually, morally, and aesthetically horrible,” Colum said.

Short on options, Owens started teaching about how the church wasn’t the building but the body. His people tried to stiffen their upper lips.

“We were trying to be like, ‘Well, if this has to happen then we have to accept it,’” Colum said.

“And then here comes a miracle,” DaRocha said.

Relief

In 2019, Owens got connected with the Southern Baptist Convention’s compassion ministry, Send Relief.

“They talked to Jaime about possibly coming into our building to do a work in Massachusetts,” DaRocha said. “They were scouting out locations and felt Boston was the perfect place to start a new extension for their organization. We happened to be a church right in the inner city of Boston. It was a miracle.”

Send Relief’s 16 domestic ministry centers focus on caring for refugees, protecting children and families, and fighting human trafficking. In Boston, they rented out Tremont Temple’s entire fifth floor and began eating lunch with the homeless, working with the victims of sex trafficking, and helping churches reach out to the growing immigrant population around them.

“They’re doing really good work,” DaRocha said. “I see their vans all over the city.”

Send Relief also partnered with the Boston Center for Biblical Counseling, which joined them in Tremont Temple’s office space. Downstairs, a Hispanic congregation had been renting space for their weekly church services; now a Korean church began doing the same thing. A Christian coffee shop is building out one of the storefronts on the ground floor.

In 2023, the city declared Tremont Temple a historic landmark, protecting it from certain kinds of development in the future.

“In the last two years, we’ve applied for three major grants for the facade project, totaling approximately $1.35 million,” Owens said. “All three were granted, nearly covering the entire project, which is soon to begin. Crazy provision!”

“God was opening these doors for us,” DaRocha said. “One thing after another started coming through.”

One Thing After Another

Things aren’t perfect at Tremont Temple. The weekly attendance is growing—and there are eight babies in the nursery—but it hovers around 100 adults, which still feels tiny in the massive sanctuary. Some of the polity is still tangled up. And the sixth and seventh floors still need renters.

But Tremont Temple will stay in the middle of Boston.

Every second Sunday, some of the congregation walks a block and a half to the oldest park in America—the 50-acre Boston Common.

“Can I talk to you for a second?” they ask anyone they find there. Then they strike up a conversation—What are you selling? What game are you playing? What do you think is the craziest thing going on in the world right now?

Sometimes people are hostile to any talk of Jesus. Sometimes they’re impatient or ambivalent. And sometimes they’re curious or enthusiastic.

Each time they go out, the Tremont Temple folks are bolder, elder Ellison Domkap said. “Almost everyone was sharing, ‘I didn’t know I could do this! I can see myself having more courage!’”

But that’s not the best part, Domkap said: “To the glory of God, we have seen some people make decisions in accepting Christ as their Savior.”

To Jane Crump, the rescued Tremont Temple has the new energy of a church plant.

“God is working,” she said. “It’s very exciting. I am old, but I hope the Lord keeps me around long enough so I can see some more seats filled. But the number of people isn’t as important as redeeming the lost and having the saints discipled.”

The financial hardship “was the worst and the best,” DaRocha said. “It turned sorrow to joy in a way only God could do. . . . If it weren’t for the Lord intervening, I don’t know where we would have been. It’s so tragic to have a church with such history close. It goes to show you that hope is real. Prayer is real. Miracles are real.”

“The Most Practical and Engaging Book on Christian Living Apart from the Bible”

“If you’re going to read just one book on Christian living and how the gospel can be applied in your life, let this be your book.”—Elisa dos Santos, Amazon reviewer.

“If you’re going to read just one book on Christian living and how the gospel can be applied in your life, let this be your book.”—Elisa dos Santos, Amazon reviewer.

In this book, seasoned church planter Jeff Vanderstelt argues that you need to become “gospel fluent”—to think about your life through the truth of the gospel and rehearse it to yourself and others.

We’re delighted to offer the Gospel Fluency: Speaking the Truths of Jesus into the Everyday Stuff of Life ebook (Crossway) to you for FREE today. Click this link to get instant access to a resource that will help you apply the gospel more confidently to every area of your life.