We can learn much about the deep longings of our communities from the buzzwords that we use and overuse.

Savor. Vulnerability. Presence. Influencer. Belong.

It’s the final word—belong—that has caught my attention and sparked immense reflection. Why has belonging become such a popular idea across secular and church cultures?

It makes sense: Many have lost, or never had, a true sense of belonging.

For all our great advances in technology, modern Americans are more distracted than ever before. Despite constant, always-on connectivity, we’re lonelier than any other human group in history. All is not well with us.

Our society has been described as a “swipe-right culture”—a reference to approving a potential date on a popular dating app. When we like something at first glance, swipe right. The moment something—whether a person, relationship, job, or community—loses its appeal, swipe left. Swipe-right culture promises freedom and autonomy: The moment you’re not satisfied, find something new. Probably by using your phone.

And it’s not just those outside the faith and the church; the search for true belonging exists within our own congregations. To whom to do we belong? Is it true we must “belong to ourselves”? And the great question that haunts so many in our day: Who are my people?

We Long to Belong

Belonging isn’t an abstract psychological state, nor is it unimportant for those of us doing “serious” church work.

Belonging is our primary human need. Beyond food and shelter, nothing promotes human flourishing like having a people and place of belonging. Research confirms that income level, marriage and children, and perceived security all pale in comparison to belonging in promoting sustained happiness. We long to belong.

The church is God’s creation to “set the lonely in families” (Ps. 68:6), to give us a place to belong. Churches and Christian organizations can promote belonging by reorienting their ministries and strategies around thriving community—by inviting people to belong, not just challenging them to commit.

Version of Belonging

In 2017, Brené Brown published Braving the Wilderness, applying her unique insights to belonging and loneliness. Brown is a social worker, professor, and popular author. Her TED talk on vulnerability has been viewed more than 40 million times, and she has become a fixture in pop culture. Yet within the evangelical church, she is a controversial figure. She often mentions her Christian faith, but her work on shame, vulnerability, and belonging come from her research in social psychology, and many believers have found her books to be a slippery slope toward self-centeredness.

While I certainly don’t agree with everything Brown says and writes, she has done the world a profound favor by reminding us of the importance of vulnerability in relationships, the need for belonging, and the significance of empathy in interpersonal support. In Braving the Wilderness, though, she makes some claims that relate to our topic, and indeed stretch the classic understanding of belonging.

Brown defines belonging as “the innate human desire to be part of something larger than us. Because this yearning is so primal, we often try to acquire it by fitting in and by seeking approval, which are not only hollow substitutes for belonging, but often barriers to it” (31–32).

Brown’s desire to establish true belonging as something far deeper than “fitting in” is noble. She continues: “True belonging . . . [is] not something we achieve or accomplish with others; it’s something we carry in our heart. Once we belong thoroughly to ourselves and believe thoroughly in ourselves, true belonging is ours” (32). So, her theory goes, we must be secure in ourselves, and then we’ll belong wherever we are. It follows, then, that there will be many times when we don’t fit in, and when we’ll be alone—in the wilderness—and yet still belong there.

I understand that her thesis is grounded in recent data from psychological surveys. I don’t doubt that’s what the data says. But I do doubt that it’s entirely true.

Belonging—Our Greatest Need

I was out to lunch with a new church member a few years ago, and he mentioned his previous graduate research (in education theory) was focused on belonging. I admitted I had no idea what he meant.

He explained: In the late 20th century, the “self-esteem” movement was in full swing until, well, it wasn’t. The reigning hypothesis stated that individuals were most fully satisfied when they had a high sense of self-esteem. Self-esteem went from a minor therapeutic theory to a dominant factor in wider culture, and thousands of parents began to instill large doses of self-esteem into their kids.

In Christ, we can find true belonging: True belonging is being fully known and being fully loved.

The rise of the self-esteem movement, however, was based more in hypothesis than in evidence. The end of the 20th century brought about a few long-term studies aimed at proving its importance. Children were indoctrinated with self-esteem (among other factors) from early childhood into young adulthood. But the research came to a startling conclusion: Self-esteem had little to no positive effect on individuals’ lives. For many, it had a significantly negative effect.

So, what single quality was most identified with satisfaction and well-being? In 1995, Roy Baumeister at Florida State published a substantial article demonstrating that the healthiest, most satisfied individuals in life are those who have a place to belong.

In other words, our deepest satisfaction comes not from achieving personal autonomy but through acceptance into unconditional love and in unbreakable belonging to a people. I feel like I’ve read that somewhere.

Belonging in the Scriptures

Belonging has deep roots in the biblical story and Christian theology. Belonging takes several forms in Scripture, but it’s not a complicated theme. There are three levels.

First, most of the references to belonging refer to one’s ownership of possessions. Second, people are often said to belong to a fixed social group—priests to the Levite division (Luke 1:5), Joseph to the house and lineage of David (Luke 2:4), and the early Christians to the church (Acts 9:2; 12:1). But there is a third and most profound sense of belonging described in the Scriptures. We belong to God and his family—a truth that itself gets expressed three ways in the New Testament.

1. We belong to God—Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

Little children belong to Jesus and his kingdom (Matt. 19:14). Those who serve the poor and marginalized in Jesus’s name belong to him (Mark 9:41). The church is the bride that belongs to Jesus, the bridegroom (John 3:29). Whoever belongs to God hears and obeys his voice (John 8:47). All those who belong to the Son belong also to the Father (John 16:15). Both Jewish and Gentile Christians belong to Christ (Rom. 1:6). Christ died so that we might no longer belong to ourselves but belong to Christ and bear fruit for God (Rom. 7:4). Without the Holy Spirit, no one belongs to God (Rom. 8:9). Whether we live or die, we belong to God (Rom. 14:8). When Christ returns, all who belong to him will be resurrected (1 Cor. 15:23).

2. We no longer belong to ourselves or to the world.

On the other hand, those who reject Jesus belong to the Devil and the kingdom of the world (John 8:44). Jesus’s own disciples belong to him, not to the world (John 15:19). We no longer submit to the rules of the world because we no longer belong to it (Col. 2:20). We no longer belong to the darkness; we belong to the light (1 Thess. 5:5, 8).

3. We belong to one another in the church.

Belonging to God is our deepest need, and yet God himself calls creation and life without human companionship and community “not good” (Gen. 2:18). To belong to God is to belong to others.

To belong to God is to belong to others.

The children of God belong to his family forever (John 8:35). In Christ, we form one body and every member belongs to all the others (Rom. 12:5). We can’t stop belonging to the body (1 Cor. 12:15–16). We do good to all people, especially those who belong to the family of believers (Gal. 6:10). At the end of days, we’ll find ourselves among the diverse multitude, the ultimate and eternal place of belonging—the Holy City (Rev. 21–22).

We belong to God, not to ourselves or to the world. Belonging to him means belonging to his people, his family. It means belonging to the church.

Good News of Belonging

This biblical insight into how and where we belong brings us full circle. From the perspective of Scripture, we can make a slight but essential change to Brené Brown’s thesis: When we belong to God, not ourselves, we can then and only then fully belong to others.

Brown’s stated desire is to find that “belonging is in our heart and not a reward for ‘perfecting, pleasing, proving, and pretending’ or something that others can hold hostage or take away” (35). Indeed, only belonging to God—and through him, to one another in the church—can offer this secure position.

When we’re secure in Christ, we’ll be established and rooted in how he has made us, and we will belong to him and, in a sense, to ourselves. We can become who we were meant to be—fully adopted and secure children of God.

When we’re secure in Christ, we’ll be established and rooted in how he has made us, and we will belong to him and—in a sense—to ourselves. We can become who we were meant to be—fully adopted and secure children of God. We “come home” to ourselves in this significant sense. The layers of protection that have surrounded us like shells can begin to fall away, and true spiritual transformation can begin.

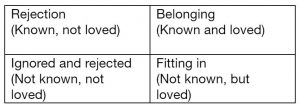

In Christ, we can find true belonging, for true belonging is being simultaneously fully known and fully loved.

If I might borrow the 2 x 2 chart from Andy Crouch, belonging results from being both known and loved. Being known without being loved is rejection. Being loved without being known is merely fitting in. Being neither loved nor known is being ignored and rejected entirely.

For those of us struggling to feel a strong sense of belonging, then, the question becomes: How do I belong?

How to Belong

In view of the biblical vision for belonging and with the support of ongoing research, four steps toward a more complete spiritual belonging emerge.

1. Believe

In one sense, those who believe already belong to God. As Jesus told the Pharisees, “You do not believe, because you do not belong to my sheep. My sheep hear my voice. I know them, and they follow me” (John 10:26–27, NRSV). As Jesus’s followers, we believed in him ultimately because we belonged to him. The two are held together, and it follows that to grow in belonging to God and his people, an increasing faith and trust in Jesus is essential.

In our churches, “belonging before believing” is true insofar as belonging roughly means feeling loved and welcome, which is absolutely vital and a frequent forerunner to saving faith. With regard to formal belonging, however, we summon people to believe in order to belong. The deep, universal longing to belong leads us here—to abiding faith in Christ and membership in his fold.

2. Stay

There are many causes for the lack of belonging in American culture; chief among them is our transience.

When my wife and I first married, we were living in the college town of Columbia, Missouri. We were excited to move out and get on with our lives in a big city. To have an “impact” for Christ—or so we’d been trained to believe—we needed to go somewhere bigger, faster, and better than our current place. A decade and three kids later, we longed to return home—where we were known and loved and could create a place of belonging for others.

How does our belonging to God and others suffer by frequent transition?

In the name of upward mobility, young people often move off for college, take a job in another city, move for another promotion, and so on. By their 30s, they’ve probably held more jobs and lived in more homes than their parents ever did. There’s nothing inherently wrong with transience and upward mobility, but we have to ask: What does this do to our souls? How does our belonging to God and others suffer by frequent transition?

3. Move In

But just believing in Christ, joining a church, and remaining in one place doesn’t guarantee true belonging. We must consistently move in. We must move toward others, embracing a life of interdependent relationship over a life of autonomy and independence.

My default response to new people and hard situations is withdrawal, but withdrawal doesn’t create belonging and sustain intimacy. When conflict arises within the community, move toward it and seek resolution. When a need arises, step in and offer your support or resources. When others lack a place to belong, invite them into yours.

4. Make Space

To gain a sense of belonging, make space for others to belong. Take the focus off yourself. Too often, I can wait for others to check in on me, invite me over, or put together a social gathering. But when I take initiative, whether it’s inviting church friends to our home or offering to get coffee with someone outside the church, I usually find others quick to accept. My experience is that the more I take initiative to cultivate community for others, the more I feel that I belong with those people.

When we take the focus off our own need for belonging, and create space for others to belong, we find ourselves surrounded by those who are happy to have us in their lives.

This final step fits within the great paradoxes of Christianity. If you want real life, you have to give yours away. If you want to find yourself, you must lose yourself.

When we take the focus off our own need for belonging, and create space for others to belong, we find ourselves surrounded by those happy to have us in their lives.

True Belonging

To end our search for true belonging requires an awareness of self and others. Even amid a transient, unrooted, “swipe right” culture, our ultimate belonging is secure. It always has been. As the first question of the Heidelberg Catechism (1563) reads:

Q: What is your only comfort in life and death?

A: That I am not my own, but belong with body and soul, both in life and in death, to my faithful Savior Jesus Christ . . .

We belong not to ourselves but to God, and through him, to his people. At long last, our search for true belonging can have a happy ending. In Christ and among his people, we’re fully known and fully loved.

“The Most Practical and Engaging Book on Christian Living Apart from the Bible”

“If you’re going to read just one book on Christian living and how the gospel can be applied in your life, let this be your book.”—Elisa dos Santos, Amazon reviewer.

“If you’re going to read just one book on Christian living and how the gospel can be applied in your life, let this be your book.”—Elisa dos Santos, Amazon reviewer.

In this book, seasoned church planter Jeff Vanderstelt argues that you need to become “gospel fluent”—to think about your life through the truth of the gospel and rehearse it to yourself and others.

We’re delighted to offer the Gospel Fluency: Speaking the Truths of Jesus into the Everyday Stuff of Life ebook (Crossway) to you for FREE today. Click this link to get instant access to a resource that will help you apply the gospel more confidently to every area of your life.