I’ve been told I’m the guy who hates short-term missions.

Seven years ago I wrote a series of articles on short-term missions, but one in particular struck a chord: “Why You Should Consider Canceling Your Short-Term Mission Trips.” I sought to slay one of the golden calves of American evangelicalism, and quite a few folks weren’t happy about it.

Do I still believe it, seven years later? Yes—but 10,000 times more strongly. I’ve seen, experienced, and hosted trips, and I’ve watched the reporting back home (and not just from American teams) in the local church. If I had the power, I’d wipe out the majority of short-term mission trips with the wave of my hand.

What’s my rationale for this bold contention? Several things.

Research at the Mercy of Testimonies?

Our culture primarily communicates in images and stories. When many Americans see something sad, our response is, What can I do? This is honorable. We see pictures of malnourished children or orphanages that need repair or refugees that need help. So we go, and the stories seem to come to life.

We also hear stories from people who have gone on such trips. They report a renewed love for Jesus, a new passion for missions, even a call to long-term service. The impact seems enormous.

But it’s not.

Research by Robert Priest, Brian Fikkert, Dambisa Moyo, and Bob Lupton (among others) on short-term trips has shown three things:

- They don’t change participants’ lives.

- They don’t cause more people to commit to long-term missions.

- They often harm both local economies and orphans.

But here’s the problem: research rarely trumps the anecdotes that participants recount after their cross-cultural experiences. With an outsider’s view of complex cultural dynamics, we’re left evaluating short-term cross-cultural experiences based on felt needs and personal testimonies. It’s like a pastor evaluating his sermon based on how he felt about it.

But Won’t We Send Fewer Missionaries?

One faulty assumption that often drives short-term missions is that people make long-term commitments as result of short trips. I’ve heard this anecdotally recounted in my friends’ lives. This is how we often recruit people, but it’s a poor approach to mobilizing missionaries. Statistics show that while short-term missions have exploded, the number of full-time missionaries has remained the same or even decreased.

Perhaps we should at least pump the breaks on our assumptions that short-term trips are needed to recruit missionaries. Let’s say 500 go on short-term trips and, out of them, one commits to a long-term calling. Is gaining one missionary worth the cost of sending that many on short trips?

There is a similar argument that says going on a short-term trip will instill in participants a lifelong interest in missions—even if they don’t go long-term, they’ll be more likely to support those who do. But again, despite the explosion in short-term missions, giving to missionaries has not increased.

Our presuppositions seem to be flawed.

Stealing Resources?

Imagine you’re a missionary. You’ve spent years getting trained. You’ve raised money and asked hundreds of friends for support in awkward face-to-face meetings. You move overseas and then spend two years learning the language. It’s hard work, but you and your spouse become conversational, and your kids are way ahead of you.

Then your home-church network, an outside-church network, and a parachurch ministry call in succession. They want to send short-term trips to your location. They’re excited about your ministry, so they start sending teams—one per month. All of a sudden your job is to facilitate trips and serve as a translator for eager college students. The roles of discipler and evangelist are out; tour guide is in. The pressure to play host is enormous. You don’t want to be a lone ranger. You don’t want to snuff out the passion of earnest people boarding a plane.

This scenario is the experience of numerous overseas missionaries.

Here’s another situation I’ve often seen. A church struggling to support a skilled and trained long-term missionary for $200 a month won’t question raising $40,000 to send many untrained workers for a week. Churches are less likely to support a long-term missionary than to send a group of teens to paint a house or put on a VBS in a country where they don’t speak the language.

American churches often send untrained individuals from among the financially privileged on short-term trips as a means of discipleship. In doing so, we swamp long-term workers with people who have flexible schedules and eager hearts, but not a lot of skill.

Many missionaries wish they could tell you the same thing, but they’d lose support from churches if they publicly expressed this view.

Are All Short Trips Bad?

So are all short-term trips bad? Absolutely not. In another article, I’ve offered some ways forward. Having served for a decade as the leader of a missions agency that takes short-term trips, I offer eight brief ways to make them more fruitful.

1. Take short-term trips to meet crisis needs. Some needs, such as natural disasters or an influx of displaced people, long-term workers can’t handle alone. Send trained workers who will help, not hinder, their efforts. If you don’t send trained folks, you could create a second disaster.

2. Invest in long-term workers first. If you’re a smaller church with a missions budget of $12,000 and you send a short-term team for $40,000, you have things backward.

3. If you’re interested in poverty alleviation, read everything by Brian Fikkert. Then make your plans.

4. If you’re building anything without local participation, then in almost every situation, get out. The thing you’re building will most likely never be used or will be torn down. Most likely it’s a project created to give short-term teams something to do.

5. Consider sending smaller groups of the church’s most experienced, godly, and skilled members. Some of the most effective trips are elders and their wives going to encourage missionaries.

6. If you’re sending teens and college students, send smaller numbers to work with a veteran missionary who wants to disciple them. The key word for the young short-termers shouldn’t be impact, but rather learn.

7. If you’re visiting an orphanage to hold babies and play with kids, there are probably better ways to help them. The short-term team may be harming the children’s development. Instead, raise money to hire long-term staff or invest in community-development projects so that parents will be less likely to place kids in orphanages.

8. If you’re working outside the sphere of people who will be there long-term, especially national leaders, your impact will be minimal. Or it could be nonexistent, if not downright harmful.

With the financial resources to make it happen, American churches send out excited believers who desire to obey Christ. That’s a beautiful impulse. However, we need to re-evaluate if the entire enterprise is more about our felt growth, and desire to be seen as godly and self-sacrificing, than it is about supporting the long-term labors of the host team and the country they’ve been called to serve.

There are many superior ways forward. Let’s do better.

Are You a Frustrated, Weary Pastor?

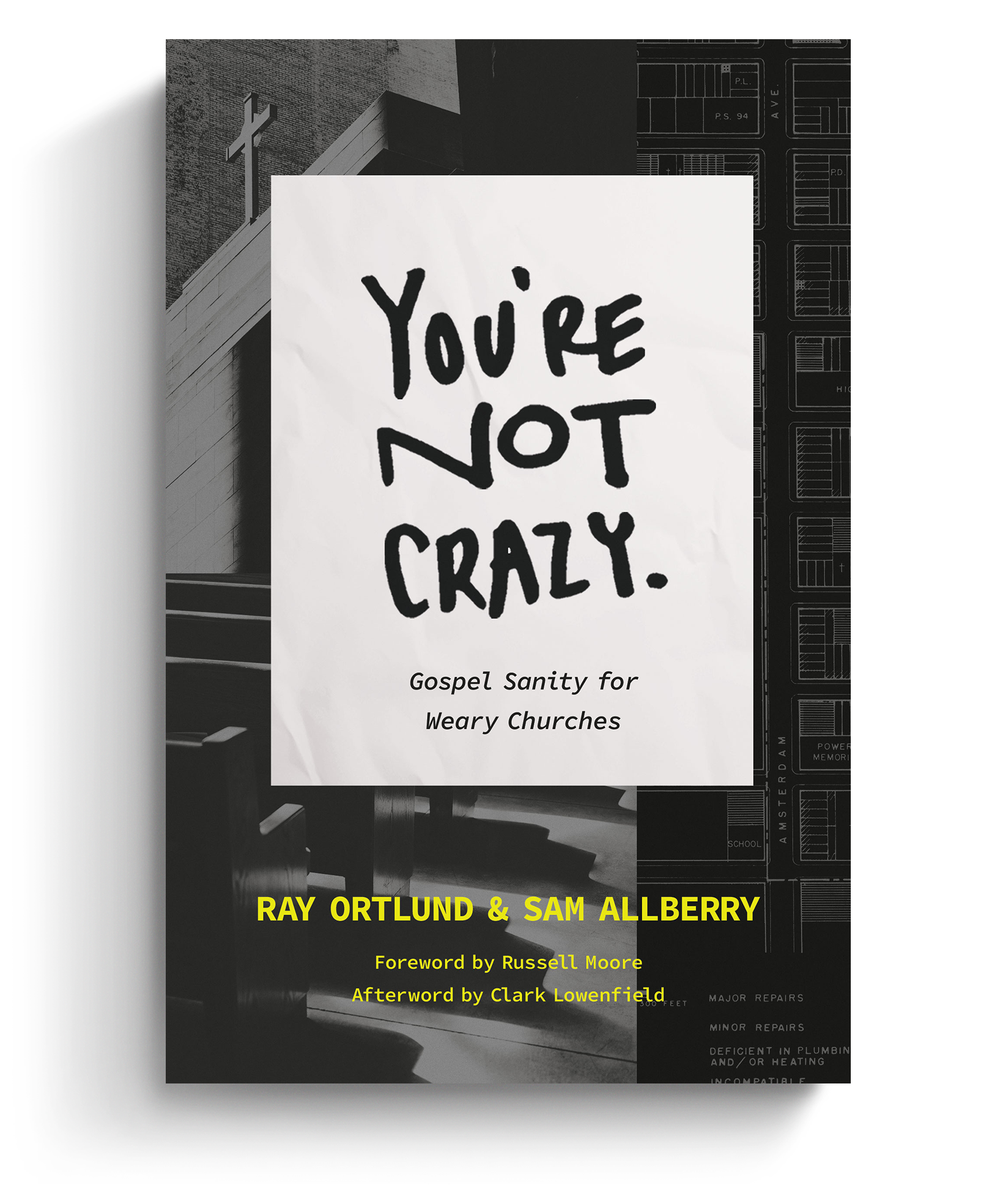

Being a pastor is hard. Whether it’s relational difficulties in the congregation, growing opposition toward the church as an institution, or just the struggle to continue in ministry with joy and faithfulness, the pressure on leaders can be truly overwhelming. It’s no surprise pastors are burned out, tempted to give up, or thinking they’re going crazy.

Being a pastor is hard. Whether it’s relational difficulties in the congregation, growing opposition toward the church as an institution, or just the struggle to continue in ministry with joy and faithfulness, the pressure on leaders can be truly overwhelming. It’s no surprise pastors are burned out, tempted to give up, or thinking they’re going crazy.

In ‘You’re Not Crazy: Gospel Sanity for Weary Churches,’ seasoned pastors Ray Ortlund and Sam Allberry help weary leaders renew their love for ministry by equipping them to build a gospel-centered culture into every aspect of their churches.

We’re delighted to offer this ebook to you for FREE today. Click on this link to get instant access to a resource that will help you cultivate a healthier gospel culture in your church and in yourself.