As it has been said, we are doomed to repeat the history we do not read. An important evangelical history—as relevant today as in the 1990s, during my undergraduate years at Wheaton College—is Mark Noll’s The Scandal of the Evangelical Mind (1994). Noll, an American historian, writes what he calls “an epistle from a wounded lover.” The occasion of his writing was the grief he suffered, as an evangelical scholar, over the “vacuity” of evangelical thought. As a movement, evangelicalism has virtues, Noll explains. Thinking isn’t one of them.

Noll traces the anti-intellectualism of 20th-century evangelical faith. Though we’re descended from the medieval monastic culture of serious learning (“Monks . . . preserved the life of the mind when almost no one else was giving it a thought”), evangelical faith has, at least according to Noll in 1994, abandoned the arts, the academy, and other realms of “high” culture. And while we have inherited a rich Protestant tradition encouraging believers to live their whole lives “coram deo” (in the presence of God), under the influence of 20th-century fundamentalists, we’ve often lapsed into dualistic thinking, dividing the sacred from the secular. Scandalously, the historic “both-and” Christian faith (both evangelism and social justice; both personal conversion and civic engagement; both piety and scholarship) has sadly become, for many evangelicals, an either-or. The scandal remains with us today.

Noll’s particular interest is this evangelical history’s effect on evangelical scholarship. My own interest in Noll’s book, as an undergraduate and 20 years later, is the helpful self-analysis it provides for our movement and its shifting points of emphases. It has left me with an important question: What is the evidence of a life transformed by the good news of Christ’s death, resurrection, ascent, and return?

Truncated Vision

As a child growing up in an evangelical church descended from the fundamentalist movement, I was formed in the kind of Manicheaean, Gnostic, and Docetic traditions that Noll illuminates. The world was a dangerous place, full of ungodly, demonic forces. Our safety was found in retreat, not engagement. The Bible provided all there was to know about ourselves, about the natural world, and about God. Curiosity, apart from biblical study, was no real virtue for the believer; the study of the humanities and the sciences, if not dangerous, was always secondary. And because we sang hymns about passing through this passing world, I had little vision for seeking the common, earthly good of my neighbor beyond sharing the Romans Road.

Mine was the A-B-C gospel my own children learned when visiting a vacation Bible school several years ago: Admit that you’re a sinner; Believe that Jesus Christ died for your sins; Confess your faith in him. On the one hand, this is the gospel—the good news heralded by the apostles as they proclaimed the matters of first importance: “that Christ died for our sins in accordance with the Scriptures, that he was buried, that he was raised on the third day in accordance with the Scriptures, and that he appeared [to many]” (1 Cor. 15:3–8). And yet, on the other hand, this A-B-C formula can inadvertently degrade, as it did in my experience, into an easy-believism whereby the gospel becomes only the means by which we enter the kingdom—and the elementary curriculum from which we soon graduate.

Noll notes that this A-B-C approach, with its (right) emphasis on personal conversion, largely grew out of the American revivalist movement of the 18th and 19th centuries. As America looked to establish her independence from Britain, there was an inevitable anti-tradition, anti-institution pulse to American Protestantism. The inward turn of this revivalist approach prepared the way for the inward turn of the church—in the late 19th and early 20th centuries—in response to the what they saw as the rising dangers of textual criticism, higher criticism, and the hegemony of science, developments over which Protestantism fractured. Mainline Protestants championed a social gospel, abandoning many tenets of historic Christian faith, while fundamentalists, fearing theological and moral drift, emphasized personal piety, withdrawal from the world, and eternal fascination with the end times.

Beauty of Orthodoxy

As a child of easy-believism with little appreciation for the gospel’s demands, I had no imagination for the breadth of God’s activity in the world and my responsibilities therein. I couldn’t make sense of Paul’s declaration that the gospel had been preached to Abraham when God told him, “In you shall all the nations be blessed” (Gal. 3:8). I didn’t understand the way in which the gospel lifted the curse of our groaning world. I saw only a world populated by souls, each one needing to be harvested before the mass of our planet burst into flames. Apart from the occasional volunteering at the local soup kitchen, worship was confined to our spiritual duties of reading our Bible, praying, showing up to church, and “keeping oneself unstained from the world” (James 1:27). I failed to realize, as Noll described of the Puritan understanding, that “a vital personal religion was the wellspring of all earthly good.” I didn’t know what it meant to pray with Jesus, “Your kingdom come, your will be done on earth as it is in heaven.”

Beginning with my Wheaton education (and Noll’s book), my adult faith has been about a recovery of the both-and beauty of Christian orthodoxy, which includes a vision of the coming kingdom that heals broken bodies as well as broken souls. This isn’t, of course, an abandonment of the doctrines of biblical authority, of personal salvation, and the eternal realities of heaven and hell. Even in my politely hostile city (Toronto), I’m praying for every opportunity to share the good news that “Christ Jesus came into the world to save sinners, of whom I am the foremost.”

But it is to say that believing the gospel—and being transformed by it—makes me concerned about seemingly “secular” issues affecting my closest neighbors, including gentrification, immigration, police brutality, and minimum-wage laws. Like my fundamentalist forebears, mine is a religion of “The Book,” “The Blood,” and “The Blessed Hope” (to borrow categories from another historian, Joel A. Carpenter). It’s also a religion commended by the blazing prophets of old and built on the longing for “justice rolling down like waters, and righteousness like an ever-flowing stream” (Amos 5:24).

I tend to think C. S. Lewis had it right:

If you read history you will find that the Christians who did more for the present world were just those who thought most of the next. The apostles themselves, who set on foot the conversion of the Roman Empire, the great men who built up the Middle Ages, the English evangelicals who abolished the slave trade, all left their mark on Earth, precisely because their minds were occupied with heaven.

That’s a history worth repeating.

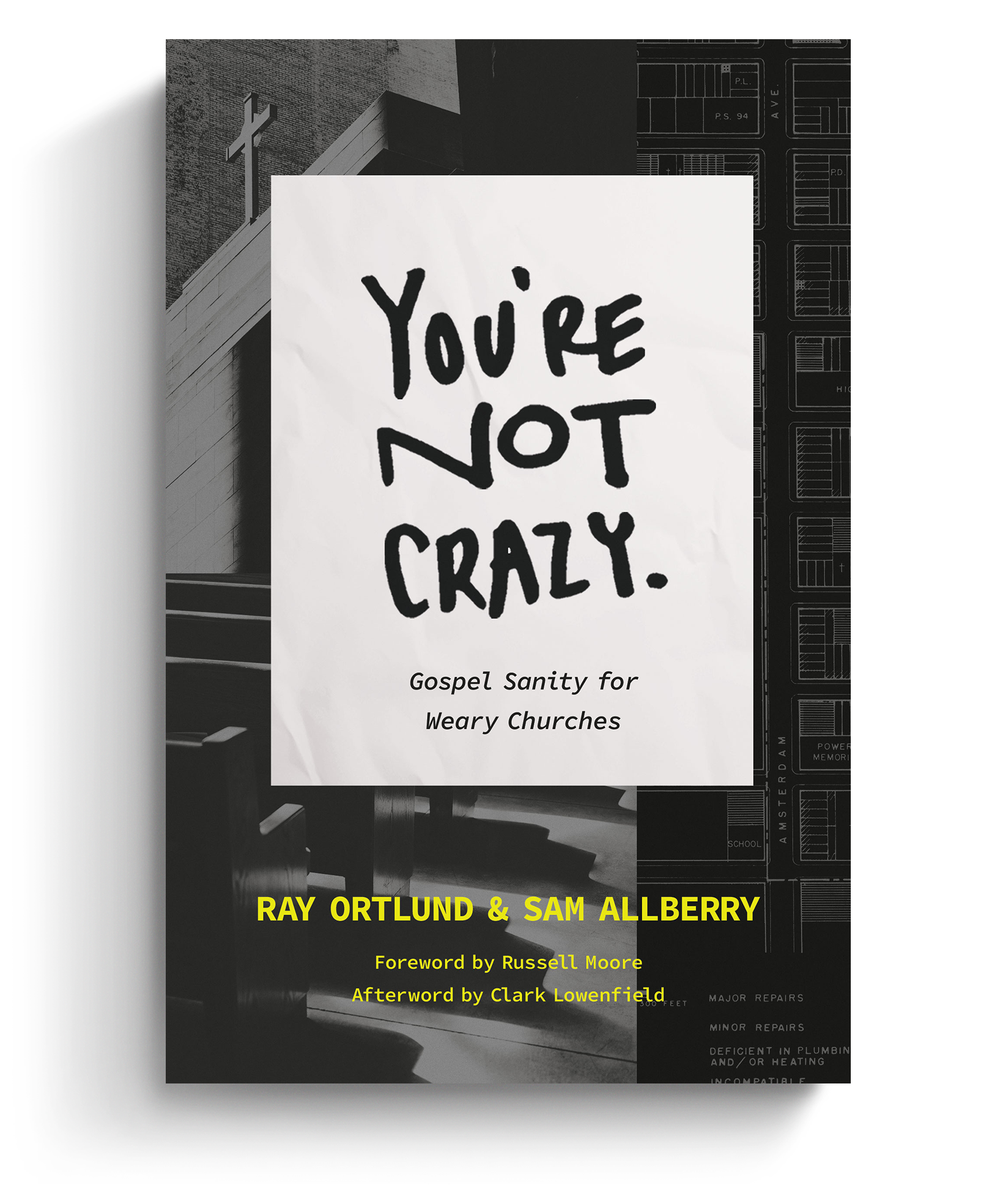

Are You a Frustrated, Weary Pastor?

Being a pastor is hard. Whether it’s relational difficulties in the congregation, growing opposition toward the church as an institution, or just the struggle to continue in ministry with joy and faithfulness, the pressure on leaders can be truly overwhelming. It’s no surprise pastors are burned out, tempted to give up, or thinking they’re going crazy.

Being a pastor is hard. Whether it’s relational difficulties in the congregation, growing opposition toward the church as an institution, or just the struggle to continue in ministry with joy and faithfulness, the pressure on leaders can be truly overwhelming. It’s no surprise pastors are burned out, tempted to give up, or thinking they’re going crazy.

In ‘You’re Not Crazy: Gospel Sanity for Weary Churches,’ seasoned pastors Ray Ortlund and Sam Allberry help weary leaders renew their love for ministry by equipping them to build a gospel-centered culture into every aspect of their churches.

We’re delighted to offer this ebook to you for FREE today. Click on this link to get instant access to a resource that will help you cultivate a healthier gospel culture in your church and in yourself.