When Tennessee Governor Bill Haslam was elected to his first office—the mayor of Knoxville in 2003—he expected the job to feel more or less like the executive positions he’d previously held at Pilot Corporation and Saks Fifth Avenue.

“I thought I was running to be the CEO of the city,” he said. “But it felt more like being a senior pastor.”

Like the church, the government serves people—issuing licenses, keeping the roads in good shape, providing fire and police protection.

“I’m somebody that doesn’t believe in big government, but I do believe the government has a vital role to play,” he told TGC. “If you need a driver’s license, you come to us. If you’re on food stamps, you come to us. If you’re incarcerated, you’re in one of our prisons. If you’re in a public school—whether in kindergarten or getting a PhD—you’re getting that from us.

“There are so many things that I think are critical for the nourishing of human society that comes through our role in the government,” he said. “So it really does feel like the chance to lead this really big service organization.”

When Haslam was elected in 2010, Tennessee wasn’t faring well. It had a median income of $45,642, nearly $10,000 less than the $55,093 national median income. Gun crime (the highest in the United States) and robberies (fifth-highest) were alarmingly common, as was unemployment (9 percent, about the national average). And income disparities between the rich and the poor were widening.

“One of the reasons for the growing income inequality in today’s world is educational differences,” Haslam said. “I’d be out recruiting businesses to come to Tennessee, and the conversations always came back to, ‘How prepared is your work force?’”

Not every job requires a college degree or certificate, “but a lot more will in the future,” he said. “The next step for us was, ‘How do we stack our system so that more people can realize the growing need for post-secondary education and then realize the opportunity is there for them?’”

In finding an answer, Haslam—a Republican, small-government advocate—offered free community college and technical school to high-school seniors, calling the program Tennessee Promise.

The first class of 16,000 Tennessee Promise students entered college in fall 2015 and had five semesters to complete their programs (because many community college freshman need remediation). Their overall success rate isn’t yet available, but so far, the numbers look good. More than 80 percent returned for their second semester. After two years, more than half had graduated, stayed in school, or transferred to a four-year university (56 percent), significantly more than their non-Promise peers (39 percent).

Haslam was encouraged enough that he extended the free college offer to all adults last summer, making Tennessee the first state to do so. (On February 15, applications for the first class opened up.)

“His initiative has brought new people into the higher-education system—students that wouldn’t have otherwise had entryway into higher education,” said Scott Sauls. He pastors Christ Presbyterian Church, where Haslam and his wife, Crissy, have been attending since moving to Nashville.

“He was doing those sorts of things before he was in politics,” Sauls said. “While he was a very top-level businessperson, and he was thinking about immigrants and refugees and his responsibility toward those who don’t have access to the resources and influence that he did. I think this is an outplaying of who he has always been.”

Politics

When someone first suggested to Haslam that he get into politics, he laughed.

“You’ve got the wrong guy,” he told them. “I have no interest.”

And he didn’t. The then-45-year-old had a brilliant career in business. (Forbes estimates his net worth as more than $2 billion, making him the second-richest politician in America after Trump.) After majoring in history at Emory University, he thought about both teaching and preaching, but instead went to work with his father. Jim Haslam had started the Pilot truck-stop chain as a single gas station in 1958; within 36 years it was the second-largest truck-stop chain in the United States.

But Pilot had never been Haslam’s dream job, so he moved to Saks Fifth Avenue as chief executive officer of the internet division in 1999. He didn’t know “anything about the internet” or “anything about fashion,” he later told the Knoxville News Sentinel. But Saks needed someone to set up a business plan and hire people, and Haslam was game.

Within a few years, Haslam was looking for something else. And he found it in politics.

“I had never, ever seriously considered running for office,” he told TGC. But he lived in Knoxville, where newly instituted term limits meant that longtime mayor Victor Ashe couldn’t run again. And after someone mentioned the idea, it stuck with him.

“I said, ‘Let’s think about it and pray about it,’” he said. He brought it to the group of five guys from Cedar Springs Presbyterian Church he’d been meeting with every Friday morning for 15 years. They told Haslam to seriously consider it.

“That got my attention,” he said. “I decided to run. And I loved it. It felt more like a calling than anything I’d ever done before.”

He served two terms as mayor, skipping out on his last year in order to take on an even bigger task: the governorship of Tennessee.

Christian Campaign

“The meek might inherit the earth, but what do they do about running for office?” Haslam said. “It’s a ‘Hey, I’m the man to solve this problem’ world.”

For the entire year before the election, “I had a stomachache,” he said. “I’d like to tell you I knew I was called and walked without any anxiety through a very difficult campaign. I’d like to say that. But I didn’t.”

Haslam wrestled with doing “nothing from selfish ambition” (Phil. 2:3–4) and, at the same time, promoting himself. He struggled to remember that everything wasn’t about him while running a campaign that inevitably was all about him.

He was careful to remember that God had called him to run for public office, but not necessarily to win.

Until he did win, with a healthy 65 percent of the vote. And then he won again, with 70 percent of the vote, four years later.

Bipartisan Education

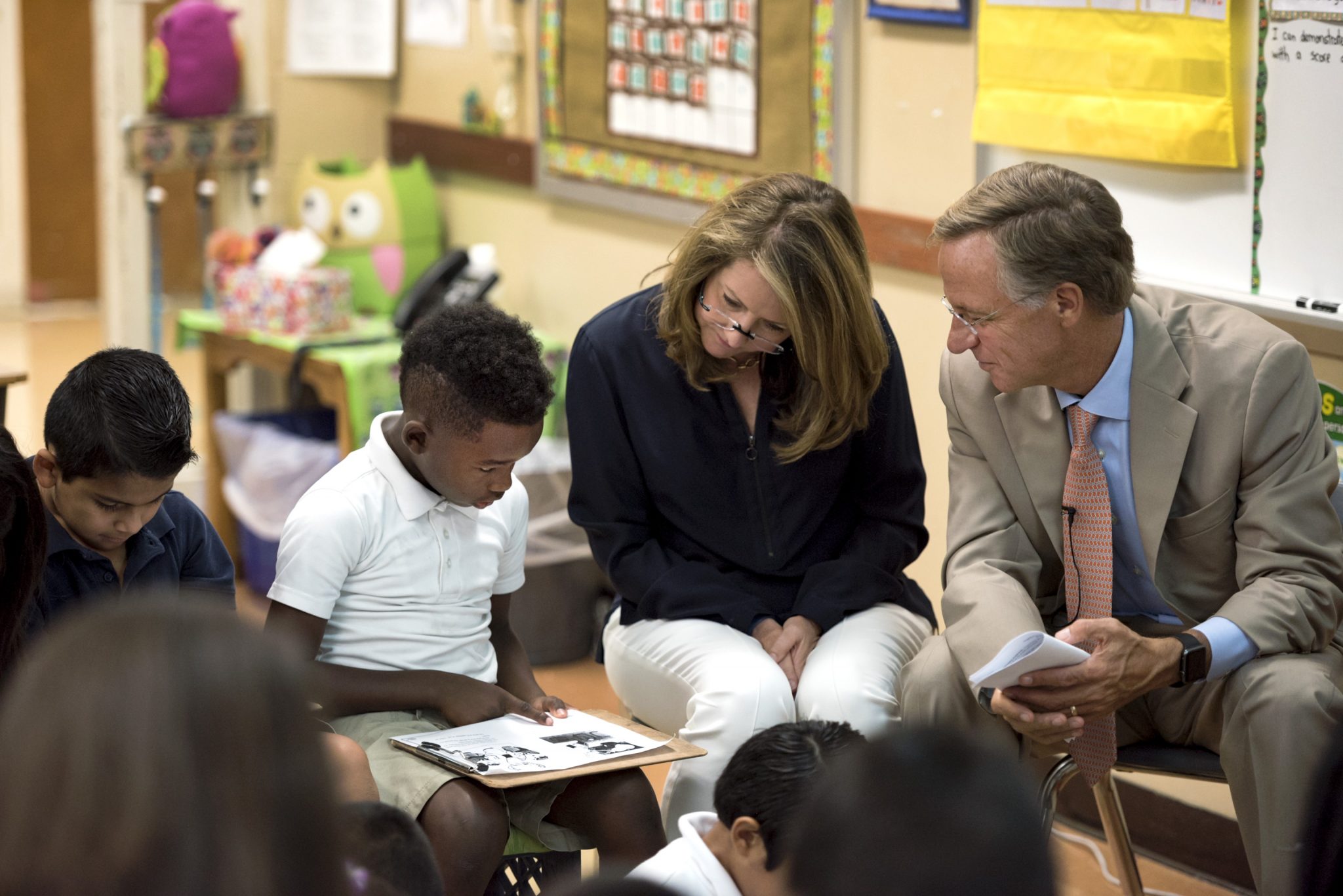

“Haslam has definitely been the education governor,” said Karen Vogelsang, Tennessee’s 2015 teacher of the year, executive director of Arise2Read, and member of Haslam’s teacher cabinet. “The thing I love about Governor Haslam is that he genuinely cares.”

Free college wasn’t Haslam’s idea—in fact, it’s become a rallying cry of his rival party. Democrat Bernie Sanders made free college part of his 2016 bid for the presidency, while the other states and cities that offer free college tuition programs—Oregon, Minnesota, New York, Rhode Island, and San Francisco—all lean Democrat.

Haslam, who often works across the aisle, doesn’t mind.

“As believers we know two things,” he said. “First, that the other person is made in the image of God. And second, that because of our own sinfulness, we could be wrong, which means the other person might be right.”

That doesn’t mean you drop your convictions, Haslam said. But it does make you more open to listening.

As believers we know two things,” he said. “First, that the other person is made in the image of God. And second, that because of our own sinfulness, we could be wrong, which means the other person might be right.

“The Democrats would argue that we need to redivide the pie, and if we could tax people more, we could take it and give it to people who need it,” Haslam said. “I’m not certain that has worked for the 50 years we’ve been trying to do it. But I do passionately believe that if we give people access to opportunity, then we can change long-term trajectories.”

He watched this happen in Knoxville, where a nonprofit group worked to cover community college and technical school tuition for high schoolers. They asked Haslam if they could partner with the city; he turned them down.

And then “I saw how much it worked,” Haslam told Inside Higher Ed in 2014. The organization helped 12,000 students pay for college in the first six years.

Its scholarships came with strings—requiring students to keep a 2.0 GPA, meet with mentors, and complete community-service hours—that he replicated in Tennessee Promise. Students are also required to carry a full class load, because part-timers are more than three-times as likely to drop out as full-timers.

Every requirement is meant to reinforce a student’s education and engagement. Because the point isn’t to get people to start college, Haslam said. It’s to get them to finish.

Free Money

Of course, free college isn’t really free, and isn’t as dazzling as it first sounds. The government doesn’t cover books or living expenses—just tuition and fees. (The average tuition for Tennessee’s 13 community colleges in 2016–2017 was $7,753 for a two-year program.) The state also doesn’t cover the entire amount—just the charges left over after a student applies for scholarships and the federal Pell grant.

Oregon, New York, and Rhode Island use taxes to pay the bill, which leaves tuition-free programs vulnerable to budget cuts. Oregon had to limit the number of recipients when they ran out of money last fall; New York only takes students whose families earn less than $125,000; and Rhode Island scaled back its originally proposed program, which was to offer two years free at any school, to include just community colleges.

Haslam took a different route, funding the $34 million annual bill with a $300 million endowment he is filling up with extra lottery proceeds.

That solution works for Tennessee, which is bound by its state constitution to pass a balanced budget every year. So while other states use lottery earnings to make up budget shortfalls, Tennessee is free to spend them on college.

But breaking the generational cycle of poverty is going to take more than offering free tuition.

Historical Poverty

“I think the concept itself is great,” said Broderick Connesero, who planted The Common church in Memphis and has worked with inner-city high-school students for 16 years. “The problem that I have experienced is that a lot of these kids aren’t necessarily prepared, even for junior college.”

Part of solving that problem is shoring up primary and secondary school system. (Haslam’s working on it—he’s increased the $5 billion K-12 budget by $1.5 billion, tweaked test standards, and toughened benchmarks.) But an even larger problem is the generational cycle of poverty, which happens when poor students who graduate from high school need to get jobs to help ease the financial burden at home.

“Even in the home, the parent is so busy raising younger siblings or trying to keep their head above water that they don’t have time to help their kid,” Connesero said. “There are so many different dynamics that play into it.”

In the Shelby County school district, which includes Memphis, “we have 40,000 kids who live in households that earn less than $10,000 a year,” District Superintendent Dorsey Hopson said.

Most of those wage-earners didn’t go to college, and don’t expect their children to either.

“[First-generation] students need a lot more hand-holding,” Haslam said. “College is a foreign world. When your schedule says MWF, they don’t know it means that class meets Monday, Wednesday, and Friday. They may think, Is that the building?”

Haslam is trying to fill that gap with mentors. Students are paired with college graduates who encourage them, remind them of deadlines, and help them navigate things such as class schedules.

“The governor is truly putting his money where his mouth is,” Hopson said. “We know that if you graduate from high school, you make more money over time than if you don’t. If you have a post-secondary degree, you make a million dollars more over your lifetime. Giving kids an opportunity to pursue a post-secondary opportunity sets them up to be able to change their circumstances in life.”

Tennessee’s free college program is “very thoughtful,” Hopson said. “What people have to do is show some patience. . . . Over time you’ll start to see more kids with the right support stick it out and earn those degrees.”

Thing is, Haslam didn’t give himself much time.

Drive to 55

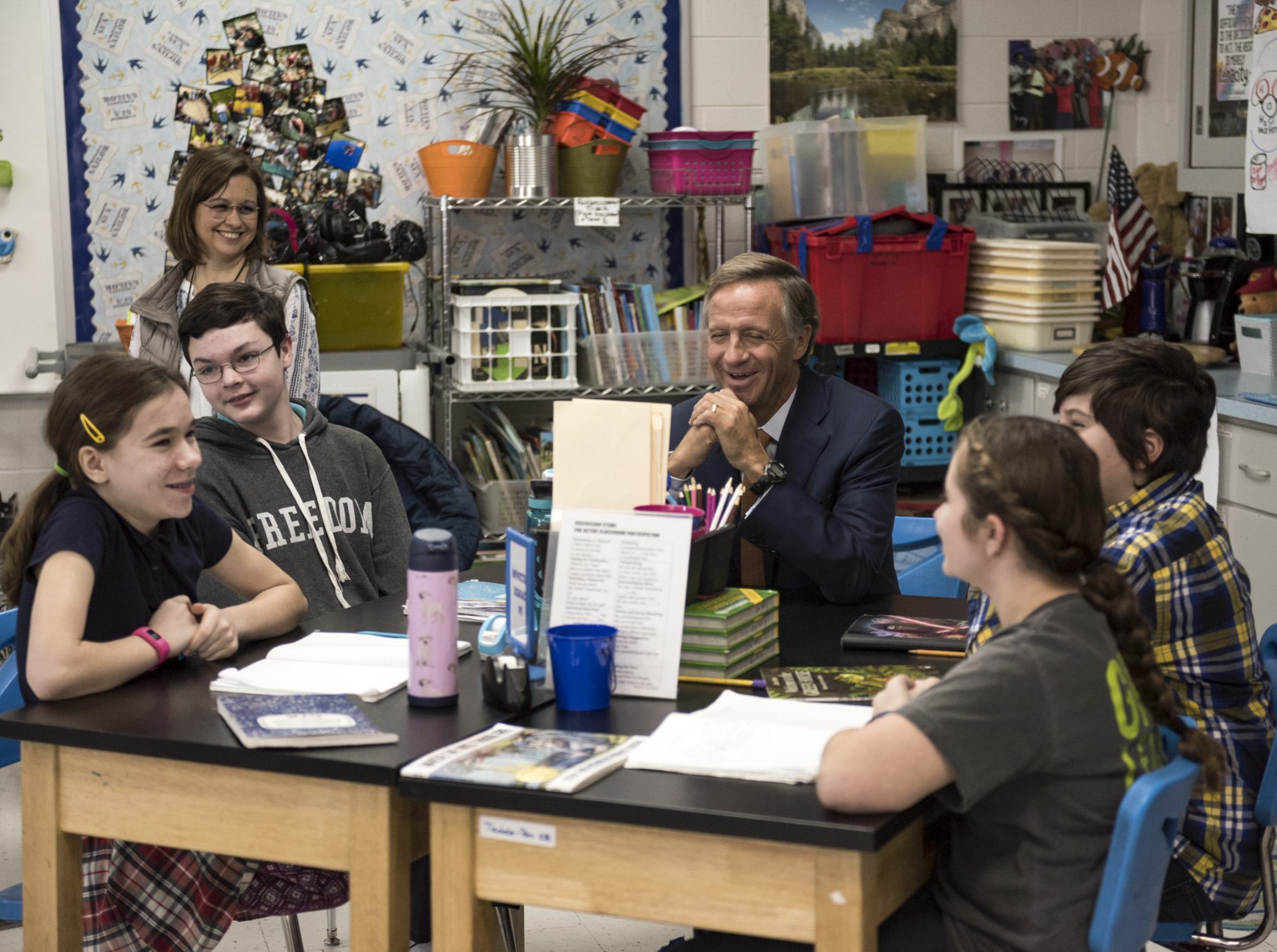

Five years ago, only a third of Tennessee adults ages 25 to 64 had a two- or four-year college degree, fewer than in 42 other states. Haslam set an ambitious goal—to raise that number to 55 percent by 2025.

When Tennessee Promise students first hit college campuses in fall 2015, they raised community college enrollment 25 percent and technical colleges 20 percent.

But it wasn’t enough. By 2017, Haslam realized that he needed 871,000 more people to earn degrees, and there were only 645,000 high-school students expected to graduate by 2022.

“We need to reach the working mother that went to college but didn’t complete, or the son with sons of his own who like his dad never went to college but knows that he needs to upgrade his skills,” he told the legislature in his 2017 State of the State address. “I am proposing that Tennessee become the first state in the nation to offer all adults access to community college free of tuition and fees.”

Tennessee Reconnect was a little different from Tennessee Promise (adults could go part-time) and a lot the same (students have to meet with advisers, maintain a 2.0 GPA, and attend consecutively).

Last May, the legislature approved.

Nine months later, in his 2018 State of the State address, Haslam told the lawmakers that Tennessee was on track to finish the Drive to 55 two years early.

Four-Year Schools

The institutions most worried about Haslam’s plan were the four-year colleges.

Offering free community college means some students who would have gone to four-year schools will choose to do their first two years closer to home, some said.

But it hasn’t been the “doom-and-gloom scenario some in higher education were predicting,” said Scott McDowell, senior vice president for student life at Lipscomb University, a member of the Council for Christian Colleges and Universities (CCCU). In fact, enrollment is slightly up at Lipscomb, with clear growth among transfers.

“Overall, the program has called attention to access [to college] more than anything else, which is a very good thing,” he said. “Individuals who never thought college was attainable now see it as a legitimate possibility.”

Indeed, freshman enrollment at Lee University in Cleveland surprised everybody and went up 10 percent the fall that Tennessee Promise went into effect.

“This is truly extraordinary,” Lee President Paul Conn stated. “With all the emphasis this year on community colleges, Tennessee Promise, and the lower cost of state institutions, we had braced ourselves for a potential downturn in our freshman class, but we’ve had just the reverse.”

Lee doesn’t offer associate degrees, but does guarantee that all community college credits will be accepted. Lipscomb went further, creating its own Promise that waives the $50 application fee, assures full credit for any community classes taken, and offers automatic scholarships of at least $10,000 for Tennessee Promise students. (Lipscomb’s tuition for 2016–2017 was $27,472.)

Four other Council for Christian Colleges and Universities members—Trevecca Nazarene Unviersity, Carson-Newman University, Johnson University, and King University—offer associate degrees, and accept Tennessee Promise students right out of high school.

Legacy

“Educating the masses is an outworking of Jeremiah 29:7, which states, ‘But seek the welfare of the city where I have sent you into exile, and pray to the Lord on its behalf, for in its welfare you will find your welfare,’” said Terence Gray, youth pastor at Downtown Church in Memphis. He works with several students he hopes will take advantage of Tennessee Promise.

“God calls his people to seek the good of the places that he has called us to dwell,” he said. “Our modern world often requires an advanced degree in order to progress and mobilize through society. A degree is often what separates economic stagnation from economic growth. I believe that providing access to that education is an act of grace that the church should initiate and participate in.”

Haslam’s not comfortable with the word “legacy,” but almost everyone uses it when they talk about his education changes.

“He’s a man with access to a lot of resources who also has a social conscience formed by the gospel imperatives of loving your neighbor,” Sauls said. “Bill really cares for the least of these, and as long as he’s in a position to leverage influence and resources to reach the greatest possibility of the tide rising for everybody, he’s going to do that.”

His ability to do so as the governor of Tennessee is set by term limits—Haslam will have to step down at the end of the year. Right now, he’s focusing on finishing well.

“Honestly, I don’t know what I am going to do next,” he told TGC. “I believed in the power of education before I came into office, and now I believe in it ten-times as much. It’s hard to imagine not being involved in education reform efforts in some way.”

Involved in Women’s Ministry? Add This to Your Discipleship Tool Kit.

We need one another. Yet we don’t always know how to develop deep relationships to help us grow in the Christian life. Younger believers benefit from the guidance and wisdom of more mature saints as their faith deepens. But too often, potential mentors lack clarity and training on how to engage in discipling those they can influence.

We need one another. Yet we don’t always know how to develop deep relationships to help us grow in the Christian life. Younger believers benefit from the guidance and wisdom of more mature saints as their faith deepens. But too often, potential mentors lack clarity and training on how to engage in discipling those they can influence.

Whether you’re longing to find a spiritual mentor or hoping to serve as a guide for someone else, we have a FREE resource to encourage and equip you. In Growing Together: Taking Mentoring Beyond Small Talk and Prayer Requests, Melissa Kruger, TGC’s vice president of discipleship programming, offers encouraging lessons to guide conversations that promote spiritual growth in both the mentee and mentor.