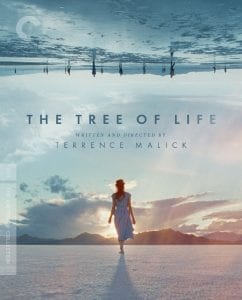

In the seven years since Terrence Malick’s The Tree of Life was released, the film has only grown in stature. Widely regarded among critics and cinephiles as one of the greatest films ever made (the late Roger Ebert included it on his final list of the 10 best films of all time), Malick’s magnum opus has also become one of the greatest examples of distinctly Christian cinematic art—and it didn’t come out of the Christian entertainment industry.

It would not be a stretch to say The Tree of Life is to cinema what Handel’s Messiah is to music or La Sagrada Familia is to architecture. It’s a Christian masterpiece.

Much has already been written about the film’s theology: how it interacts with Kierkegaard or Augustine or Dostoevsky; how it explores original sin, the relationship between nature and grace, the themes and structure of the Book of Job, and so on. Well-known theologians have written about Life, including Michael Horton and David Bentley Hart, who called it a “deeply Christian film” and “almost alarmingly biblical.” Peter Leithart wrote an entire book about the film’s theology.

I’ve written plenty about Life and its Christian themes (see here and here and here). But the recent Criterion Collection release of a new, extended version of the film (with 50 minutes of new footage) provides a fresh opportunity to revisit it. Indeed, the new version—which mostly expands the “Texas childhood” middle section—further underscores the film’s deeply Christian nature.

The new extended version of The Tree of Life further underscores the film’s deeply Christian nature.

Life is an unconventional film, to be sure, but it’s one Christians should embrace and celebrate. The film is both implicitly and also explicitly worshipful, structured as liturgy and honest about the struggles of faith. Infused with biblical words and imagery from start to finish, and lovingly rendered by a Christian artist (Malick) who ponders God, sin, and redemption in all of his films, Life is the Citizen Kane of Christian cinema: the best Christian film ever made.

A Prayer

Prayer is everywhere in The Tree of Life, noticeable even to secular critics like Roger Ebert, who called the film “a form of prayer.” It’s prayerful on at least three levels.

First, prayer shows up literally, in scenes where the O’Brien family (Brad Pitt, Jessica Chastain, Hunter McCracken, Laramie Eppler, Tye Sheridan) pray before dinner, or when young Jack O’Brien offers a humorously boyish prayer at his bedside: “Help me not to sass my dad. Help me not to get dogs in fights. Help me to be thankful for everything I’ve got. Help me not to tell lies.”

Second, the film is rife with voiceover that often articulates the silent prayers of various characters. The film’s first words are a whispered prayer by adult Jack (Sean Penn): “Brother. Mother. It was they who led me to your door.” We hear young Jack’s prayers constantly in the film’s middle section. “You spoke to me through her,” he prays at one point. “You spoke with me from the sky, the trees. Before I knew I loved you, believed in you.” The prayers are often fragmentary and hardly audible, almost like brushstrokes in an impressionistic painting (a common motif in Malick’s recent works). Sometimes we don’t know which character’s prayer it is, but that is the point. We can all find ourselves in the prayers, cries, and faith journeys of this one Texas family. Life is a liturgy that invites us all to sing along.

We can all find ourselves in the prayers, cries, and faith journeys of this one Texas family. Life is a liturgy that invites us all to sing along.

And this is the third level of prayer in the film: its very structure. Watching Life feels like attending a cinematic evensong service. Malick’s carefully chosen classical music keys us into this. Sometimes the music communicates the way creation sings of the glory of its Creator (Smetana’s “The Moldau”) or the majestic sanctity of human life (Respighi’s “Siciliana Da Antiche Danze Ed Arie Suite III,” Holst’s “Hymn to Dionysus”). Over the closing credits we hear an instrumental version of the old hymn “Welcome Happy Morning!” (the triumphant first lines of which declare: “Welcome, happy morning!” Age to age shall say; Hell today is vanquished, heaven is won today!”).

Requiems also figure prominently into the film’s soundtrack, starting with Taverner’s “Funeral Canticle” at the beginning, Preisner’s “Lacrimosa” (from “Requiem for My Friend”) in the middle, and the majestic Agnus Dei from Berlioz’s “Requiem Op. 5 (Grande Messe des Morts)” in the finale. The Latin lyrics of this final song provide a beautiful benediction, as the images on screen evoke resurrection, renewal, and “amen” hands lifted to the heavens:

Lamb of God, who takest away the sins of the world, grant them everlasting rest. Thou, O God, art praised in Zion and unto Thee shall the vow be performed in Jerusalem. Hear my prayer, unto thee shall all flesh come. Grant the dead eternal rest, O Lord, and may perpetual light shine on them, with thy saints for ever, Lord, because thou art merciful. Amen.

A Problem

The musical prominence of requiem in The Tree of Life is fitting, because at its heart, Life is about death. The problem of pain. Evil. Suffering. Sin. Mortality. It’s about feeling the lack and loss of Eden; longing for the restoration of shalom. It’s about the struggle of faith. How do we believe in resurrection in a world of ubiquitous death? How do we believe in a God who is supposedly in control of all this?

The musical prominence of requiem in The Tree of Life is fitting, because at its heart, Life is about death. The problem of pain. Evil. Suffering. Sin. Mortality. It’s about feeling the lack and loss of Eden; longing for the restoration of shalom. It’s about the struggle of faith. How do we believe in resurrection in a world of ubiquitous death? How do we believe in a God who is supposedly in control of all this?

Sean Penn’s character (like Ben Affleck’s in To the Wonder or Christian Bale’s in Knight of Cups) is a proxy for Malick himself, and most of Life seems to exist in his mind and memory—a collage of the people, places, images, and ideas that led him to (or back to) Christian faith. The film is bookended by Penn, whose adult Jack begins the film as a wanderer in a spiritual desert. These scenes are full of the sort of empty hedonism and disorientation that have characterized the spiritual quests of Malick’s most recent films, Knight of Cups (2015) and Song to Song (2017).

“How did I lose you? Wandered. Forgotten,” we hear Jack pray, lamenting lost faith as he wanders among women, alcohol, and cocktail parties. Lost in a world of metal, glass, and neon light (James Turrell’s “The Light Inside” makes a cameo), Jack feels disconnected from goodness, truth, and beauty. “Remember,” Jack whispers, as we see a woman on a cell phone in an art museum—a symbol of the inattentive distraction that plagues our technological age. Jack longs for transcendence again. Restored faith. The movie is a reflection on that spiritual recovery.

Jack’s journey back to faith (visualized as a doorway he finally walks through) comes, as his opening prayer suggests, by way of his younger brother R. L. and his mother, Mrs. O’Brien (Jessica Chastain). Reflecting on his brother’s death (when he was only 19) and his mother’s consequent grief, Jack begins his remembrance and a conversation with God that will occupy the brunt of the movie.

The conversation starts from God’s point of view, with an epigraph from Job 38:4–7: “Where were you when I laid the foundations of the earth? . . . When the morning stars sang together, and all the sons of God shouted for joy?”

Mrs. O’Brien turns the question back on God after she loses her son. As the film’s famous creation sequence begins (which envisions those moments when God “laid the foundations” and “the morning stars sang together”), we hear her pray: “Lord, where were you? Did you know? Who are we to you? Answer me.”

Later in the film there is a remarkable scene in a church, where we hear a large chunk of a sermon on Job (delivered by real-life Episcopal priest Kelly Koonce):

Misfortune befalls the good as well. We can’t protect ourselves against it. We can’t protect our children. We can’t say to ourselves, even if I’m not happy, I’m going to make sure they are.

We vanish as a cloud. We wither as the autumn grass, and like a tree are rooted up.

Is there some fraud in the scheme of the universe? Is there nothing which is deathless? Nothing which does not pass away?

We cannot stay where we are. We must journey forth. We must find that which is greater than fortune or fate. Nothing can bring us peace but that.

The journey of Life’s characters—chiefly Jack—is a journey forward to the God who is greater than fortune and fate, the eternal one who answers our longing for the deathless, the Tree of Life who restores what has been rooted up by sin.

Bible’s Grand Narrative

The Bible begins with a Tree of Life in Eden (Gen. 2:9) and ends with a Tree of Life whose leaves “were for the healing of the nations” (Rev. 22:2, 14, 19). The Tree of Life bookends the Bible, symbolizing the once and future kingdom of God in its perfection: Paradise before it was lost, and Paradise when it is ultimately restored. The arc of the Bible is from Tree of Life to Tree of Life, and the path from one to the other necessarily involves a tree of death (1 Pet. 2:24), the cross of Christ that bridges the breach between us and God.

The arc of the Bible is from Tree of Life to Tree of Life, and the path from one to the other necessarily involves a tree of death.

As its title suggests, Malick’s The Tree of Life has this redemptive structure in mind. The film’s nearly three-hour journey can roughly be mapped onto the creation, fall, redemption, restoration structure of the Bible’s Tree-to-Tree arc. The film is not a gospel tract, and its theology is perhaps too ambiguous at times. But for those with ears to hear and eyes to see (like Jack O’Brien in the film), Life’s journey can be beautifully faith-building.

I. Creation

Life’s creation sequence occupies a little more than 30 minutes of the film. It begins with the now-legendary “universe creation” sequence (which famously prompted many walkouts during the film’s 2011 theatrical run), in which the conventional narrative is paused and the audience is invited to imagine what God’s “when I laid the foundations of the earth” actually looked like. Set to the operatic dirge of Preisner’s “Lacrimosa,” the sequence—full of nebulae, forming stars, DNA, nascent cells, early plant life, even dinosaurs—is unmistakably liturgical: an awe-inspiring hymn that echoes the praises of Psalms 8, 19, and 139, among others.

Life’s creation sequence occupies a little more than 30 minutes of the film. It begins with the now-legendary “universe creation” sequence (which famously prompted many walkouts during the film’s 2011 theatrical run), in which the conventional narrative is paused and the audience is invited to imagine what God’s “when I laid the foundations of the earth” actually looked like. Set to the operatic dirge of Preisner’s “Lacrimosa,” the sequence—full of nebulae, forming stars, DNA, nascent cells, early plant life, even dinosaurs—is unmistakably liturgical: an awe-inspiring hymn that echoes the praises of Psalms 8, 19, and 139, among others.

The film’s creation section continues in a more down-to-earth register with the O’Brien family’s own creation in 1950s Waco, Texas: Pitt and Chastain’s romance, followed by the birth of sons Jack (Hunter McCracken), R. L. (Laramie Eppler), and Steve (Tye Sheridan). The scenes of the boys’ early childhood are lovely and Edenic, evoking Paradise before the Fall. To underscore the parallel, gardening looms large, with the boys seen working and keeping the garden (Gen. 2:15) with their dad. But there are also boundaries and rules laid out. Dad points out the property line and tells Jack not to cross it. Mom reads the boys a line from Beatrix Potter: “Don’t go into Mr. McGregor’s Garden.” The forbidden is made clear; the possibility of transgression is foreshadowed.

II. Fall

The fall section of Life is the longest, lasting more than an hour in the film’s middle section, as innocence gives way to rebellion in young Jack. Dinner-table defiance. Sibling rivalry (“Who do you love the most?” Jack asks his mom). A snake slithering in the front yard right by mom’s heel (a nod to Gen. 3:15). The boys come into an awareness of darkness, evil, suffering, mortality. They see prisoners in handcuffs, men with disabilities, a boy with a burn scar, a friend whose father abuses him, a three-legged dog. Awareness of good and evil. In new material added to the extended version—and another nod to Job—a tornado hits Waco, leaving destruction in its wake (Malick’s camera takes particular note of uprooted trees). The world is not as it was meant to be.

With both his earthly father (Pitt) and God himself (relationships that often feel intertwined), Jack questions the rules and why his father isn’t also bound by them: “He says ‘don’t put your elbows on the table.’ He does.” Jack demands a share in God’s omniscience: “I want to know what you are. I want to see what you see.”

A turning point comes when one of Jack’s friends dies while the boys are swimming together. Significantly, a new scene in the extended version shows these boys in church immediately before the swimming accident, talking about baptism with their pastor. The boy who dies is presumably in this class with Jack, and thus Jack faces the problem of evil early. What kind of God lets a good, church-going, catechism-trained boy die while swimming with friends? Jack questions God’s goodness:

“Where were you?” Jack asks God, mirroring his mom’s same question earlier in the film. “You let a boy die. You let anything happen . . . Why should I be good if you aren’t?”

From there Jack’s descent accelerates. When his dad leaves on a business trip, Jack and his brothers get into mischief with a coterie of neighborhood friends. They chase girls, tie frogs to bottle rockets, destroy property, steal things. They pick “forbidden fruit” from someone’s vegetable garden. “I don’t think that’s ours,” one boy says. “Who cares,” the ringleader responds. “They belong to everyone.”

Jack acts up in school, gets into fights, and his mom meets with teachers and principles. His jealousy of brother and rage against father both increase (at one point he prays for God to kill his dad). He lusts after a neighbor woman and experiences the shame of sexual sin. And like Adam and Eve in Genesis 3:7, his eyes are opened. A brief scene shows him holding a towel around his waist to cover his nakedness as mom looks on from the hallway. He closes the door in embarrassment.

Jack’s fall dominates this sequence, but his father also has his own descent. Prone to anger, control, and roughness with his wife and kids, Mr. O’Brien’s downfall is ultimately his pride. “Make yourself what you are . . . Take control of your own destiny,” he tells his boys. “I can redeem myself,” he insists. The ultimate self-justifying striver, Mr. O’Brien measures himself by achievements and good works. When late in the film he loses his job, he can’t understand why God would inflict such a lot on so deserving a man: “I never missed a day of work. I tithed every Sunday.”

Why, God? Like his son Jack, Mr. O’Brien faces his own Job-like dilemma.

III. Redemption

“What have I started? What have I done?”

Jack’s redemption (which occupies most of the film’s third act) begins with awareness of his own depravity. He’s a sinner, and he knows it.

“I always do stupid things. I want to be little again.” he tells his mom. “How do I get back where they are?” he ponders as we see the brothers swim in the purifying waters of a river and waterfall.

The next scene hints at an answer. Dad returns from the business trip, and the boys run out to hug him, relieved to have his order and tough love back in the house. Redemption, this sequence suggests, will come through relationship.

The film’s redemptive turn follows Jack’s lowest moment of sin. He betrays the trust of his brother R. L. and shoots his finger with a BB gun. Immediately guilt-ridden, Jack’s voiceover is essentially a paraphrase of Romans 7:15: “What I want to do I can’t do. I do what I hate.”

What follows is a remarkable scene of repentance, forgiveness, and reconciliation between the two brothers. “You can hit me if you want,” Jack tells R. L., knowing he deserves payback for his sin. But R. L. shows him grace, pretending to hit him with a piece of wood (a nod to the cross?) but smiling at him instead. “I’m sorry,” Jack says, as his brother tenderly touches him on the shoulder and head—gestures of reconciliation we see repeated between various characters the rest of the film.

After this pivotal scene, Jack’s faith seems to solidify. He understands and receives grace. As the camera pulls up along the contours of a large tree, revealing a God-like perspective, Jack prays: “What was it you showed me? I didn’t know how to name you then. But I see it was you. Always you were calling me.”

Having reconciled with his brother, Jack then has a wordless reconciliation scene with his father in—where else?—the family garden. Communion again. Shalom. The music in this sequence is a piano rendition of the Respighi excerpt we hear earlier in the film during Jack’s birth. The subtle musical cue signifies what this garden scene is for both Jack and his father: a rebirth.

The song continues as Mr. O’Brien has his own moment of repentance and redemption, admitting the folly of his self-justifying pride: “I wanted to be loved because I’m great, a big man. I’m nothing. Look: the glory around us, the trees, the birds. I lived in shame. I dishonored it all and didn’t notice the glory. A foolish man.”

For Malick in all of his films, sin is often tied to missing the glory: ingratitude, a shunning of God’s good gifts. Modernity and technology compound it (remember the woman on the cell phone in the museum?), distracting us from the “the glory around us.” If the way of nature leads us to conquer and protect what we think is ours, the way of grace leads us to receive what we don’t deserve—gladly welcoming God’s gifts, chiefly himself. As in Eden, so in our own world: God wants to be with us, but we so often want to go it alone.

If the way of nature leads us to conquer and protect what we think is ours, the way of grace leads us to receive what we don’t deserve—gladly welcoming God’s gifts, chiefly himself.

A blink-and-you’ll-miss-it addition in the Life extended version is a shot of a magazine article featuring Albert Schweitzer: a renaissance man (Bach-loving organist, theologian, physician, Nobel Prize-winning philosopher) who Mr. O’Brien (himself a Bach-loving organist) likely admires. But as successful as Schweitzer was—the article headline calls him “The Greatest Man in the World”—he understood that life is less about what we achieve than what we receive. “Our inner happiness depends not on what we experience,” Schweitzer once said, “but on the degree of our gratitude to God, whatever the experience.”

Whatever the experience. Fortune or misfortune. The three main characters in Life (Mr. and Mrs. O’Brien and Jack) all experience the Job dilemma. How can one love God when he doesn’t seem good? But they all eventually grasp what the preacher in the earlier church scene suggests about loving God whatever the experience:

The very moment everything was taken away from Job, he knew it was the Lord who’d taken it away. He turned from the passing shows of time. He sought that which is eternal.

Does he alone see God’s hand who sees that He gives, or does not also the one see God’s hand who sees that He takes away? Does he alone see God who sees God turn His face towards him? Does not also he see God who sees God turn his back?

Faith is a choice. We choose to love God and receive his love, even when his back seems turned. Even when the gospel does not produce prosperity. Even when you lose your job, your home, your child, or you are sent away to boarding school (as happens to Jack at the end of the film).

“Unless you love, your life will flash by.” We hear Mrs. O’Brien’s voiceover as young Jack stands on the lawn of his Christian boarding school, looking more mature and at peace—a cross looming large on the building behind him.

IV. Restoration

The film’s final 10 minutes depict restoration. Having walked through the door of faith, adult Jack (Penn) visualizes the new creation. To the Agnus Dei liturgy of Berlioz, we see resurrection, people literally rising from graves. We see images evoking Revelation 21: a lamp (v. 23), an open gate (v. 25), a bride (vv. 2, 9), the nations walking (v. 24). We see sin defeated, as a jester mask falls into the depths of the sea. No more death or mourning or pain.

The film’s final 10 minutes depict restoration. Having walked through the door of faith, adult Jack (Penn) visualizes the new creation. To the Agnus Dei liturgy of Berlioz, we see resurrection, people literally rising from graves. We see images evoking Revelation 21: a lamp (v. 23), an open gate (v. 25), a bride (vv. 2, 9), the nations walking (v. 24). We see sin defeated, as a jester mask falls into the depths of the sea. No more death or mourning or pain.

But where is Christ in all this? For Jack, his little brother R. L. stands as a symbol of Christ. Why does Malick name this character R. L.? Perhaps it stands for “Resurrection and Life,” the name Christ calls himself in John 11:25–26. Notice how Jack prays in the film scene: “Brother. Keep us. Guide us. To the end of time.” As if to answer this “guide us” petition, R. L. then says “Follow me,” echoing Christ’s words in Matthew 4:19.

Why does Malick name this character R. L.? Perhaps it stands for “Resurrection and Life,” the name Christ calls himself in John 11:25–26.

Hints at an association between R. L. and Christ—and it is merely an association, not a “Christ figure” allegory—are sprinkled elsewhere in the film. In the church scene when the preacher says, “Is there nothing which is deathless?” the camera is on R. L. and then pans to a stained-glass depiction of Christ. At various points in the film we see R. L. handle fish. When we hear the word “hope,” R. L.’s face is on the screen. When Jack shoots R. L., R. L. forgives him. We see images of R. L. holding a light in the darkness. And then there is the film’s final line. With her hands lifted in prayerful worship, as the music plays a recurring “Amen,” Mrs. O’Brien says “I give him to you. I give you my son.” Her grief over R. L.’s death has been transformed into freedom and worship.

And while the words make sense in the particular context of the O’Brien family’s story, like everything else in Life they have another meaning too. We leave the film with these words ringing in our ears: “I give you my son.” The words mean one thing to Mrs. O’Brien, but they speak another word directly to us, to all who have ears to hear. In a film about receiving God’s gifts and noticing the glory, the greatest gift is the Son. The resurrection and the life. A shoot from the stump of Jesse (Isa. 11:1), the true vine in which we find life and fruitfulness (John 15:1–8). The ultimate Tree of Life.

“The Most Practical and Engaging Book on Christian Living Apart from the Bible”

“If you’re going to read just one book on Christian living and how the gospel can be applied in your life, let this be your book.”—Elisa dos Santos, Amazon reviewer.

“If you’re going to read just one book on Christian living and how the gospel can be applied in your life, let this be your book.”—Elisa dos Santos, Amazon reviewer.

In this book, seasoned church planter Jeff Vanderstelt argues that you need to become “gospel fluent”—to think about your life through the truth of the gospel and rehearse it to yourself and others.

We’re delighted to offer the Gospel Fluency: Speaking the Truths of Jesus into the Everyday Stuff of Life ebook (Crossway) to you for FREE today. Click this link to get instant access to a resource that will help you apply the gospel more confidently to every area of your life.