For someone who never really fit in, Julius Kim is remarkably confident.

Born in Los Angeles to Korean parents, Julius was 2 when his father moved the family back to Korea to restart a defunct electronics manufacturing company.

Julius spent elementary school balancing between Korean culture and his English-speaking, private school on a U.S. Army base. When he was 12, the Kims moved back to California, where he continued to tip between a Korean home and an American school.

“The not-belonging feeling started then,” Julius said of middle school. “In Korea, switching between my English-speaking friends at school and Korean friends at home, I learned how to code-switch [behave differently in various settings to meet cultural expectations].”

He was code-switching, but his was the dominant culture. Once he moved back to the United States, however, he began to experience racial discrimination. Worse yet, when he went back to visit Korea, he no longer fit. Both his language and cultural skills were off.

“I’m in this liminal experience of being in-between,” Julius said. “I’m in both cultures, but I don’t belong to either.”

That’s never changed, though the feeling was worse when he was younger.

“A lot of people in their teen years try to find their identity,” he said. “I struggled tremendously, wanting to have blond hair and blue eyes. I went through self-hatred, not seeing the wonderful gifts and strengths and opportunities I had.”

It felt like being an exile—infuriating and depressing and scary.

But Julius had two enormous advantages. The first was a passel of Korean American friends living the same strange homeless experience. When they encountered one another, at church, summer retreats, or schools, they connected quickly and deeply.

The second was his father, who had wrestled with his own homelessness—kicked out of his home at 12 years old, surviving a brutal civil war, and immigrating to America twice. Through it all, Gwan Kim held onto his faith so tightly that even now, at 87, he’d move to Israel tomorrow to do mission work if his wife would agree.

With his father setting an example and his friends beside him, Julius found his way through the sometimes painful, sometimes funny experience of inhabiting a culture not really his own. He learned how to find his identity in something deeper, how to be gentle with others who don’t fit in, and how to speak prophetically to a culture with blind spots.

On February 1, Julius will take the helm at The Gospel Coalition as president. In a country where Christians are increasingly marginalized, believers can sometimes feel infuriated and depressed and scared. Growing secularization can feel like a slow push into exile.

But if there’s one thing Julius knows, it’s how to flourish in a culture not his own.

Conversion of Gwan Hae Kim

Julius learned how to be a pilgrim from his father.

Born to a wealthy landowner—Julius’s grandfather owned a successful logging company and served as a policeman during the Japanese occupation—Gwan grew up eating the best food and wearing the best clothes. He lived in a large compound that housed many in the Kim clan. In addition to school, he and his cousins had private tutors.

But when Gwan’s mother gave birth to only one child, his father regarded her as cursed and beat her often. (Her fingers would grow permanently mangled from never healing correctly.) The mother and son were forced to move to another house, and when Gwan was 12, his father tried to set it on fire.

After a year at her brother’s home, Gwan’s mother moved with him to a small town outside of Seoul where she scraped out a living selling fish and salt. It was 1945 and a terrible time to be a single parent in Korea—as the Americans closed in, the Japanese occupation grew increasingly desperate. There was hardly money for food, and certainly none for school.

But in 1945, after the Japanese surrendered and went home, they left wide gaps in the economy. Needing people to run the railroads, the Korean government offered free education to anyone who would study transportation. Gwan applied and received the scholarship that provided not only tuition, but also room and board during the week.

He was still in junior high when a friend invited him to a local Methodist church. Curious to find out more about Christianity—all his teacher said was that it was started by the apostle Paul—he went.

Gwan’s mother was nominal Buddhist, and she didn’t like the way he kept eyeing Christianity. She tried locking him out of the house on the nights he went to church, but he’d just stay with friends.

“I loved church,” Gwan told TGC. “I loved to study the Bible.”

For three years, Gwan went to high school during the day and studied the Bible on Wednesday nights and Sundays. His country, supported and influenced by the United States, built a government, worked to fill in the economic and educational gaps left by the Japanese, and became more and more Christian.

But in June 1950, North Korean troops—backed by China and the Soviet Union—marched south, determined to unite the peninsula under communism.

Gwan’s school shut down; eventually, overtaken by North Korean troops, his church would close too. Since North Korean soldiers executed Christians as American spies, Gwan fled back to his father’s village, then to his uncle’s house in the country.

“I was so scared,” he said—scared of being killed by North Korean troops, of being forced to join them, of starvation. By the end, half of his high-school friends were missing or dead. “I had nothing but prayer.”

But that was enough.

“I knew God was with me,” Gwan said. “I trusted him. I knew he was listening. He helped me out whenever I had a problem or a difficulty. I am so grateful for his love and that he called me to become a Christian.”

He doesn’t remember doubting God. “My family problems, my country problems—they’re all circumstantial,” he said. “They were bumps to my faith, but nothing else.”

That sounds wrong. Gwan’s problems—a father who banished him, a mother who locked him out of the house, a country that couldn’t feed or keep him safe—aren’t incidental. Then again, neither are shipwrecks, imprisonments, and beatings. Perhaps not surprisingly, Gwan sounds a lot like the first Christian he ever heard of (2 Cor. 4:17).

Godly Life

Julius was born in Los Angeles, almost a decade after Gwan moved there in 1959 to get his master’s degree in electrical engineering.

When Julius was 2, Gwan moved his family back to Korea. Gwan began making computer memory systems for military jets; at its height the company had around 1,000 employees.

Every Wednesday after lunch, he’d bring in a different local pastor to preach the gospel. “Over the years, hundreds came to the Lord,” Julius said. He grew up watching his father care for his employees, support local ministries, and serve as a lay leader in the church.

“My dad is one of the most important mentor figures in my life,” he said. “His godly life had such an impact on me.”

Because Julius went to a private, English-speaking school on the United States Eighth Army base, when the family moved back to California in 1980, the transition “wasn’t so bad,” he said.

But that didn’t mean it was great. His darker skin and eyes stood out. His parents had deep emotions about things—the 38th Parallel, food, high school—that didn’t bother the parents of his American friends. His family valued different things. They liked different food, preferred different home décor, and enjoyed different weekend activities.

But while the Kims didn’t match the dominant culture, they fit perfectly in another one. In 1980, the year Gwan moved his family back to California, he joined 290,000 other Korean immigrants who had crossed the same ocean in the same direction.

They were part of a wave pushed off by the lifting of American immigration restrictions in 1965. The Korean immigrant population in the United States rose from 39,000 in 1970 to 568,000 in 1990 to 1.1 million in 2010.

Wounded by the wars, new to American culture, and generally ambitious and bright—the time has been dubbed South Korea’s “brain drain”—early Korean immigrants had much in common. They wove tight communities, gathering together in neighborhoods, churches (often Presbyterian), and homes.

“I don’t remember a Sunday night when we didn’t have 30 to 40 adults and kids in our home,” Julius told TGC. “We’d all eat dinner together, and then the adults would do their Bible study, and the kids would play games or watch TV. . . . Monday through Friday I’d go to school with white kids, and on the weekends I’d go to this immigrant church and hang out with Korean kids who were trying to make sense of this bilingual life.”

The second generation—and the 1.5 generation, which spent part of childhood in Korea—was better assimilated into America but still felt Korean. They spoke English but understood some Korean. They liked to watch movies but also go out for Korean food. They ran around with friends but always took off their shoes at the door and showed respect to their elders. (When at school, they did that by looking adults in the eye; at home, they did it by avoiding eye contact.) When meeting Americans, they’d stick out their hands and introduce themselves. When meeting Koreans, they’d wait to be introduced by the appropriate social acquaintance.

“Some of us are more Korean, some of us are more American, and some of us are confused in the middle,” said Presbyterian pastor Owen Lee, whose parents immigrated in 1970, a year before he was born. He’d end up at seminary with Julius.

The experience can be confusing, frustrating, and embarrassing.

“It wasn’t really until college that I knew who I was,” said Robin Lee, Owen’s brother. “On the one hand, you had this self-hate. You so wanted to be white but knew you weren’t. What made that painful was to go back to Korea to see relatives, but you didn’t speak the language well and didn’t dress right. You weren’t accepted in Korea either.”

Balancing between the East at home and West outside was “a constant reality, the lens through which you live every moment of your life,” Owen said. “You’re kind of in two cultures, and kind of in neither one. You find comfort in knowing you aren’t alone.”

Not Alone

Perhaps the best part of living in no-man’s-land is the other people living there with you.

“When you see Korean American Christians together, you’ll often see instant friendship and laughter,” Robin said. “From the minute you see another [Korean American Christian], you have like six things in common.”

His deep friendship with Julius started on Robin’s visit day to Westminster Seminary California. Robin had grown up in a non-Reformed Christian church, but went to a Korean-speaking Presbyterian church in college. They’d recommended Westminster California to him, and seeing Julius—who was then the student body president—helped confirm it.

“I was like, ‘Oh, I guess this theology isn’t just for the Dutch,’” Robin remembers.

Julius didn’t grow up Reformed either, and was only at Westminster California because it was physically closer to his home than the other seminary that accepted him. He was scared to death of being a pastor, enrolling only on the encouragement of his pastor and father.

“I was very young and immature,” Julius said. “Yet, out of respect to my dad and pastor, I said, ‘Let’s try it.’”

He was newly married, and his parents and hers counseled the couple to stick closer to home for their first year.

Sounds smart, Julius and his wife, Ji Hee, thought. Julius could take some Greek and Hebrew, get a few general classes out of the way, and then transfer to Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary.

But the Westminster California professors “opened up Scriptures to me in a way I’d never seen before,” Julius said. “I basically got introduced to covenant theology, to Reformed theology, and the way of reading the Bible through the covenant. And I had never seen the Bible that way before, so I just ate it up.”

He was blown away by the doctrine of justification and by seeing Christ through the Old Testament. It was liberating and, at the same time, anchoring.

Like his father, he grabbed on.

Unplanned Path

In 1982, there were seven Korean-language churches in the PCA. By 1992, there were five presbyteries, 41 churches, 53 missions churches, and 139 teaching elders.

The booming Korean-speaking churches were always looking for help with the English-speaking second generation. While Julius worked on his MDiv, he led college and young-adult ministries at a Korean American PCA church. “I’d been Reformed for like six months,” he said. “I was part of a group of young Korean American pastors learning what it means.”

He’d study during the week, lead Bible study Friday nights, do leadership training or premarital counseling for college students on Saturdays, and preach and serve a full day on Sunday.

“I’d walk into church feeling overwhelmed and guilty that I didn’t do enough work on my sermon,” he said. “I’d do my best to preach and was amazed at how the Lord would use a crooked stick like me to draw straight lines.”

He and Ji Hee wanted to be overseas missionaries, but his professors told him he ought to get a PhD.

“Getting an MDiv was hard enough,” Julius told them. “I have plenty of tools I can use to go build in other places.”

“Just pray on it,” they told him.

He ended up at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School, studying historical theology under John Woodbridge. No worries, he and Ji Hee told themselves. We’ll head overseas after this.

Julius was working on his dissertation proposal when he got the call from his alma mater in California, asking him to consider teaching.

It seemed to him the height of foolishness. I need to go overseas for 20 years first and then I may have some wisdom to share, he thought. But Ji Hee told him they should at least pray about it.

“So that’s what I did,” Julius said. “That’s been my life pattern, whenever I get approached about an opportunity. I never immediately say no, even though I know I’m not going to do it.”

He knew he wasn’t going to Westminster California—until he sensed God telling him he was.

“I’ve been so thankful for the culture of community here,” he said. “So many were so patient with me in those early years.”

Sometimes he was worried that he was mainly hired for diversity’s sake. But even if that’s partially true, “the Lord used that moment in time to bless both the institution and me,” Julius said. “Even things that may come across as unjust—in God’s perspective, he uses everything for our good and his glory.”

Julius has spent the last 20 years at Westminster California, teaching homiletics, cross-cultural missions, pastoral ministry, and the history of preaching. He’s been writing (including a preaching textbook), teaching (including a year in Korea), and serving as an associate pastor at New Life Presbyterian Church in Escondido, California.

But he never lost that itch for something broader, something missional.

Prepared for the Moment

While Julius was at Trinity, he took a class from a professor named Don Carson. About 10 years after Julius enrolled, Carson and Redeemer Presbyterian Church pastor Tim Keller would convene a Council that founded The Gospel Coalition (TGC). The coalition aimed to be a fellowship of evangelical leaders in the Reformed tradition who wanted to refocus churches “so that we truly speak and live for him in a way that clearly communicates to our age.”

Their project grew quicker than anyone expected.

Today, TGC has 21 regional chapters in the United States and Canada and 12 more across the globe. In the last decade, the annual number of online users has grown from 1 million to 32 million, making it one of the largest Christian websites in the world.

When Carson transitions from TGC’s first president to his new role as TGC’s theologian at large in June, Julius will step in. He’ll be pastoring pastors and teaching teachers across the globe, thinking about the best ways Christians can live out the gospel in a culture—at least in the West—that’s losing its religion.

“It’s uncanny how the Lord has taken me through so many different experiences that seem to fit what I think TGC is already doing but can do more of,” Julius said. “I’m amazed at how the Lord has used so many things in my life to prepare me for this moment.”

Not the least of which is a history of not fitting into the wider culture.

Christians Without a Culture

For a long time, America felt like the chosen land for many Christians. In public schools, kids learned that God created the world. In courtrooms, judges quoted Scripture. In town halls, mayors prayed before city council meetings. Every president except Thomas Jefferson and Abraham Lincoln has belonged to a Protestant—or, in the case of John Kennedy, Catholic—denomination.

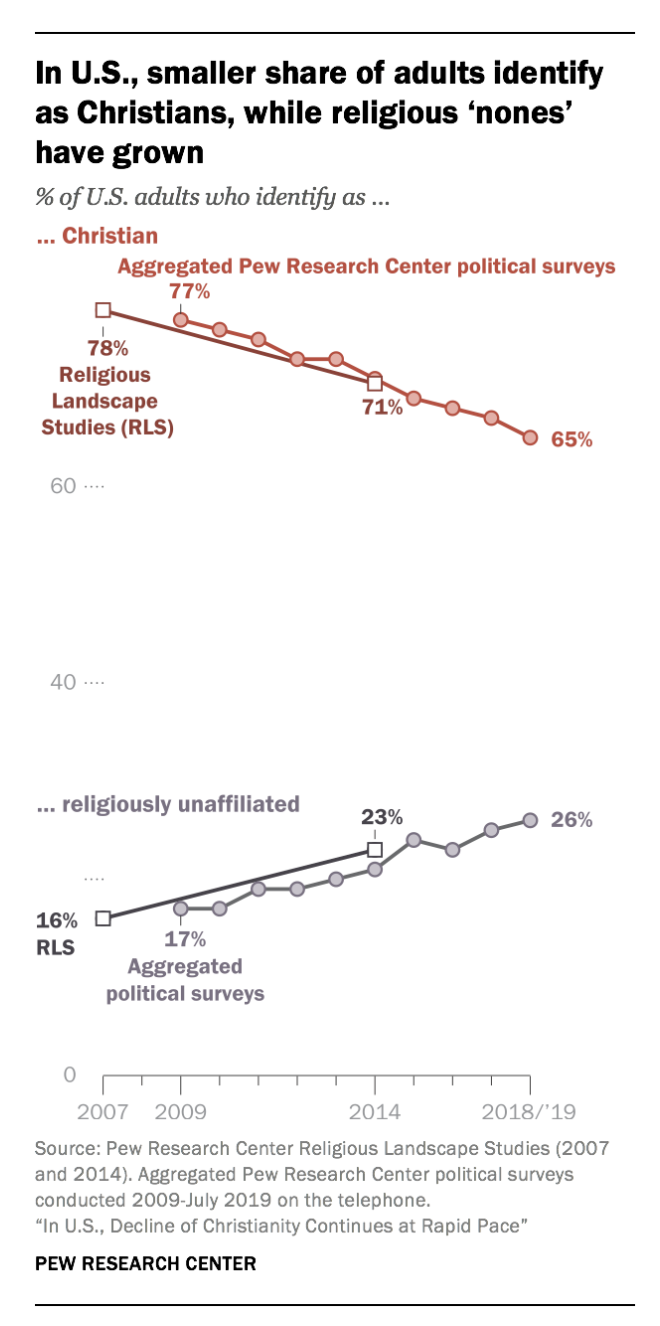

But that’s changing. From 2007 to 2018, the percent of Americans who identified as Christian dropped from 78 percent to 65 percent, while the religiously unaffiliated grew from 16 percent to 26 percent. Abortion and same-sex marriage are now legal, while church attendance, daily prayer, and belief in God are all declining.

But that’s changing. From 2007 to 2018, the percent of Americans who identified as Christian dropped from 78 percent to 65 percent, while the religiously unaffiliated grew from 16 percent to 26 percent. Abortion and same-sex marriage are now legal, while church attendance, daily prayer, and belief in God are all declining.

Orthodox Christians are starting to feel like exiles. (In Europe, the largest religious group is now non-practicing Christians.)

“Welcome,” Owen said. Korean American Christians “have already been at this party for a long time.”

Long enough to learn some tips.

“We recognize that our identity is found in something other than the passport we carry or the language we speak or the letters behind our names,” Westminster California president Joel Kim said. “We don’t truly belong this side of glory. This is a temporary home, a tent made with human hands. We hold things here loosely.”

But not too loosely. Christians should love and enjoy their temporary home as a gift from God, witnessing and serving and working for the good of those around them. “You’re just doing it with a passport in your back pocket reminding you that your identity isn’t found in those things, but in something—or in this case, someone—else,” Joel said.

Living on the margins is difficult. But it also has some big advantages, Julius said. “It’s given me sensitivity to those on the margins, who don’t belong. Also, it provides an opportunity to be prophetic, to say, ‘There’s more to this life—something better, greater, more beautiful.’”

Living between cultures hasn’t made Julius scared—in fact, his pastor Ted Hamilton calls him “fearless.” It hasn’t made him cynical—his wife calls him “engaging, thoughtful, hopeful, and passionate.”

Part of that bold happiness is the personality God gave him, almost certainly bolstered by the close camaraderie of his friends and steady example of his father—the only octogenarian in the Evangelism Explosion class at his church.

Being a pilgrim “is such an important theme for me,” Julius said. “My hope is that TGC will remind people this is not our home, but that we belong to another person and another place. The more we understand that, the more we will think rightly about our lives and relationships, our dreams and goals.”

Involved in Women’s Ministry? Add This to Your Discipleship Tool Kit.

We need one another. Yet we don’t always know how to develop deep relationships to help us grow in the Christian life. Younger believers benefit from the guidance and wisdom of more mature saints as their faith deepens. But too often, potential mentors lack clarity and training on how to engage in discipling those they can influence.

We need one another. Yet we don’t always know how to develop deep relationships to help us grow in the Christian life. Younger believers benefit from the guidance and wisdom of more mature saints as their faith deepens. But too often, potential mentors lack clarity and training on how to engage in discipling those they can influence.

Whether you’re longing to find a spiritual mentor or hoping to serve as a guide for someone else, we have a FREE resource to encourage and equip you. In Growing Together: Taking Mentoring Beyond Small Talk and Prayer Requests, Melissa Kruger, TGC’s vice president of discipleship programming, offers encouraging lessons to guide conversations that promote spiritual growth in both the mentee and mentor.