The first time I taught the Sermon on the Mount I was in my early 30s, just beginning to grasp the extent of my inadequacy as a Bible teacher. I confess that I thought teaching those three chapters in Matthew would be a snap. They contained, after all, some of the most familiar passages in all of Scripture. I knew for certain that I didn’t know Nahum or even Nehemiah, but Matthew 5-7 had been taught to me in bits and pieces my whole life. I had memorized the Lord’s Prayer as a child. I had sung songs in Sunday school about the wise and foolish builders. I’d sat through a sermon series entitled the “Be-Happy-Attitudes.” I owned a T-shirt that read “Shake and Shine” from a women’s retreat about being salt and light. My corner-cutting plan was to string together all those various pieces into one semester-long study.

But I discovered as I compiled that study that my very familiarity with the words of the Sermon on the Mount had bred, if not contempt, certainly carelessness. Over the years, my piecemeal exposure had reduced Jesus’ longest recorded message to nothing more than a handful of self-help sound-bites on how to pray, handle money, or deal with anger. As I prepared to teach, Jesus’ sermon unfurled as a sweeping declaration of the character, influence, and actions of a citizen of the kingdom of heaven, articulated with perfect intent by the King himself.

But I discovered as I compiled that study that my very familiarity with the words of the Sermon on the Mount had bred, if not contempt, certainly carelessness. Over the years, my piecemeal exposure had reduced Jesus’ longest recorded message to nothing more than a handful of self-help sound-bites on how to pray, handle money, or deal with anger. As I prepared to teach, Jesus’ sermon unfurled as a sweeping declaration of the character, influence, and actions of a citizen of the kingdom of heaven, articulated with perfect intent by the King himself.

No doubt when Jesus’ freshly minted disciples seated themselves at his feet on that mountainside 2,000 years ago, they had no idea what he was about to utter. I suspect they had their own expectation of what it would mean to be in the inner circle of the king prophesied to sit on David’s throne, a vision that probably did not include poverty of any kind, or mourning, or meekness, or hunger and thirst. Nor did it likely include showing mercy, trading outward purity for inward purity, making peace, or enduring persecution. I suspect their visions of walking closely with Jesus involved being the strongest rather than the weakest, the greatest rather than the least, the first rather than the last. Jesus’ sermon would have completely toppled their eager hopes to reign and rule with him in power, popularity, and ease.

But as I became reacquainted with the sermon, considered for the first time in its entirety, I found that it toppled my own expectations as well. Rather than provide me with a checklist of righteous behaviors, it asked of me the unthinkable: an impossible righteousness, one that exceeded the most righteous human example I could imagine. Not only did Jesus mean for me to obey outwardly, he meant for me to obey inwardly as well. In his kingdom there would be no walking the line, no asking, “How close can I get to sin without sinning?” In his kingdom, motive mattered as much as action. Here was no moralism. Here was a righteousness only possible by means of a changed heart. As Frank Thielman has put it, “In short, the Sermon shows us what life should look like for a heart that has been melted and trasnformed by the gospel of grace, while also making clear the true nature of God’s standards of righteousness—high standards which mean that our right standing with God is ultimately dependent on the grace of the One who tells us of them.”

John Stott has noted of its modern hearers that the Sermon on the Mount is “probably the best known part of the teaching of Jesus, though arguably it is the least understood, and certainly it is the least obeyed.” This was the case with me, wearing my “Shake and Shine” T-shirt, living in such a way that I was indistinguishable from citizens of earth, professing all the while to be a citizen of heaven. Like the disciples, I wanted following Jesus to be about power, popularity, and ease. I thought I knew the Sermon on the Mount, but it turned out that the Sermon on the Mount knew me.

Famous Last Words

Any public speaker will tell you to reiterate your most important point at the end of your message. Perhaps this is why we’re fascinated with the final words of famous people. When Peter the Great, czar of Russia, passed away in St. Petersburg in 1725, his famously ambiguous last words to those gathered around him were, “Give back everything to . . . ”

A bit of a cliffhanger, to say the least. But we find no such ambiguity in the parting words of Jesus, both at the end of the Sermon on the Mount and also at the end of his earthly ministry. Jesus closes his mountaintop sermon with an exhortation not merely to hear his words but to obey them (Matt. 7:24). Similarly, his final words to his close associates in Matthew 28 are spoken on a mountaintop, and his “next steps” are once again clear:

All authority in heaven and on earth has been given to me. Go therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, teaching them to observe all that I have commanded you. And behold, I am with you always, to the end of the age.

We are readily familiar with the opening phrases of the Great Commission, but the final clause of Jesus’ famous last words often lies forgotten in the shadows—“teaching them to observe (NIV: obey) all that I have commanded you.” Consistently, Jesus’ parting words call us to obey. If we are to fulfill the Great Commission, we must understand and teach others to obey what he commanded. What better place to begin to honor Jesus’ famous last words than by gazing with fresh eyes on his familiar first words?

I was wrong that studying those three chapters in Matthew would be easy, but it was well worth the effort. And 12 years later I am still learning from them. Why should we study the Sermon on the Mount? Because it will challenge us to think differently about Jesus. It will challenge us to think deeply about grace and law. And it will challenge us to think soberly about what it means to be a disciple. In short, it will do for us what it did for its original hearers: it will re-orient us to understand that, as one of the sermon’s most quoted expositors observed, the call to follow Christ is nothing less than a call to come and die. Death to sin through the gracious atonement, daily death to self through sanctifying obedience, and thereby, new life in the kingdom of heaven, which is even now at hand.

Consider Jesus’s Generous Grace with This Free Ebook

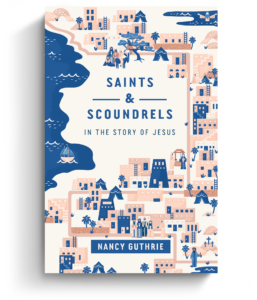

John the Baptist. Judas. Zaccheus. Caiaphas. We could quickly label these individuals as heroes or villains—but each of their experiences with Jesus provides a unique and unexpected glimpse of his generous grace. What might we have overlooked in their familiar stories?

John the Baptist. Judas. Zaccheus. Caiaphas. We could quickly label these individuals as heroes or villains—but each of their experiences with Jesus provides a unique and unexpected glimpse of his generous grace. What might we have overlooked in their familiar stories?

In Saints and Scoundrels in the Story of Jesus, seasoned bible teacher Nancy Guthrie provides readers with a fresh look at some of the most well-known personalities described in the Gospels.

We’re delighted to offer this ebook to you for FREE today. Follow the link for instant access to a resource that reminds us of the only hope for supposed saints and scandalous scoundrels—the mercy of God