Today’s interview is with Dr. Bruce Hindmarsh, the James M. Houston Professor of Spiritual Theology and Professor of the History of Christianity at Regent College, Vancouver, British Columbia. He is the author (with Craig Borlase) of the new book Amazing Grace: The Life of John Newton and the Surprising Story Behind His Song.

[TK] To start with the most obvious question, what has made the hymn “Amazing Grace” so powerful for such a wide range of people?

[BH] First, there is the marriage of the words and the tune. It is hard to separate the two. We don’t know what tune was used when it was first sung, when John Newton introduced it to his Olney parish church 250 years ago. But about 200 years ago the words found the tune we all recognize today.

The music of Amazing Grace comes from an old southern shape-note tune called “New Britain.” It is based on the raw five-note pentatonic scale that is so central to folk and roots music in many places around the world, including of course the blues—the cousin to black gospel.

Beyond the tune, I think the song has endured and continued to move people because it taps into a universal sense that humans need grace.

It is somewhat surprising that a hymn that in its opening stanza expresses robust gratitude for having received grace (“that saved a wretch like me”) has become a heartfelt prayer for grace in times of tragedy. The words acknowledge, however, that there is grace for the human condition with all its wretchedness, lostness, and blindness.

This has helped singers past and present to reckon with inconsolable loss when this comes. It is good to be able to affirm that when evil has done its worst, grace still has the last word.

You were already an expert on John Newton going into this project. [See Hindmarsh’s excellent John Newton and the English Evangelical Tradition.] What surprised you about Newton or “Amazing Grace” as you and Craig Borlase worked on this book?

More than thirty years ago, I began research on John Newton for my doctoral thesis at Oxford, and I trawled through hundreds of manuscripts in dozens of archives. I focused primarily on his contribution to the Evangelical Revival in Britain. In many ways, he epitomized the early evangelical movement, standing at its mid-point theologically and at its center spiritually.

For this book, though, a biography, I had to re-visit Newton’s early life and later life with greater attention. I found so much to connect with in terms of his humanity:

The young child who lost his mother and whose father was severe and overbearing. The teenager who made reckless decisions and was reckless in love. The young man who nearly died, far from home, alone, abused, and unloved.

The pastor whose best friend was suicidal and given over to spiritual despair. The gentle spiritual guide who wrote to offer wise personal counsel to thousands by letter. And the old man who has to reckon publicly with his early life as a slave trader at the same time that his beloved wife was dying of cancer.

At so many points, I could identify with John Newton as a struggling human being, a man who had to face up to his sinful past, but whose humble dependence on Christ deepened over the years.

Many know that Newton was once involved in the slave trade, and that he became an abolitionist. Fewer know that it took him a long time after his conversion to become convinced that slavery was immoral. How did he eventually change his mind?

It is important for people to know that Newton’s dramatic conversion in in the midst of a north Atlantic storm in 1748 did not lead him immediately to leave the slave trade. That is the narrative that we feel like we want, yet that is not what happened.

Newton did begin to change as he experienced God’s mercy, but the slave trade was so widely accepted that it would take time for him to realize that he was blind to its atrocities. He looked back later and wrote with contrition, “Custom, example, and interest had blinded my eyes.”

There is an enormous tension in the part of the narrative where Newton is writing in his spiritual journal on the quarterdeck while slaves are in chains below. But it is important that we feel this tension. It is like two tectonic plates overlapping and we can feel the tremors.

This is important because we need to consider how easily we can be self-deceived and condone horrific wrongs if they are widely accepted by our society—even as we say our prayers.

Later, Newton condemned the slave trade, and he was part of a wave of growing anti-slavery sentiment in the 1780s. The story is complex, but the scholar John Coffey thinks Newton probably held such views already in the early 1760s.

When he did finally reckon with the iniquity of the slave trade, he made a public confession, and then devoted himself to destroying the system. He wrote and spoke against the trade. He gave evidence twice to committees of the House of Commons. He encouraged William Wilberforce in his efforts.

The troubled Christian poet William Cowper played a major role in Newton’s hymn-writing. What was the nature of their collaboration?

Cowper became Newton’s neighbor at Olney not long after recuperating in an asylum from a severe mental illness. The two became fast friends and Cowper became like an unpaid associate pastor in the community. They wrote a large number of hymns together for weekly services. Cowper’s hymns, such as “God Moves in a Mysterious Way,” still speak with tremendous power today.

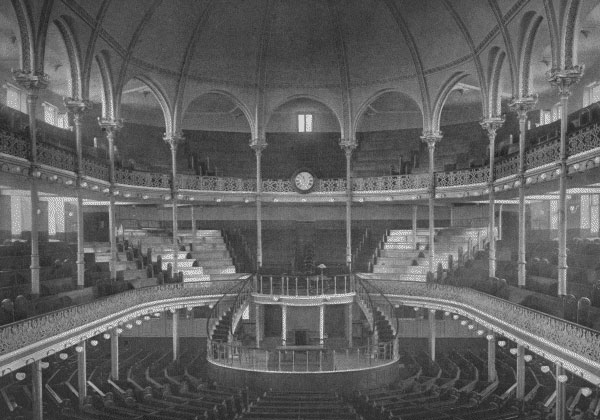

However, the day that John Newton introduced “Amazing Grace” to the parish was Cowper’s last time in church. He descended again into unremitting depression and came to feel he was uniquely damned by God. Newton and his wife were on suicide watch for him for months on end, and they really cared for him.

Although they drifted apart in later years when Newton moved to London, their affection remained. And Newton continued to believe that God’s grace was with Cowper, even though he could not feel it.

You call this book a “dramatized biography.” What does that mean, and what does this format allow you to do that traditional biography wouldn’t?

In most of my books, written for other historians, I cannot write more than one or two sentences without a footnote. But Craig and I wrote this book for a general audience. We wanted it to read like a novel, to tell Newton’s dramatic story vividly. We wanted to “show” not “tell” Newton’s story.

The advantage of this approach is to provide the reader a front-row seat to the narrative, like viewing live theatre or a film. This was the best way to help the widest possible audience of readers to experience Newton’s life for themselves, and to go through his experiences in real time.

We followed some strict conventions about how we did this. Craig and I did a lot of research to recreate some plausible dialogue and imagined scenes, but this is based on a close reading of the sources, including some newly discovered manuscripts. We didn’t just make things up to add color or interest. Mostly, we tried instead to see, hear, and feel the story. In fact, in several places we have quietly corrected details that were mistaken in earlier biographies.

In the end, this demanded more, not less of me as a historian. I had to “see” in my imagination what clothes John Newton was wearing (Did he have knee buckles where his stockings met his breeches?). I had to see the hole of the starboard bow of the ship (Was that why they went off course to the north in the mid-Atlantic?). I had to learn the ethnography of the Sherbro peoples in Sierra Leone and picture every mile of the Kittam River, and so on.

All this served the book, since we want the reader to experience the story from the inside. In the end, if we are able to see ourselves in Newton, just as we do in the song “Amazing Grace,” we will see something more of God’s grace. Above all, we come to realize that like Newton we need grace not only because of the terrible things that may have been done to us, but because of the things we ourselves have done. The title of the book is, after all, not Amazing John Newton, but Amazing Grace.

Book links here are part of the Amazon Associates program.