My Baylor colleague Philip Jenkins has a fascinating post at the Anxious Bench blog on Billy Graham’s Cold War context in the 1950s. Here’s a sample:

Though in later years Graham was known as a moderating voice within the evangelical movement, his missions of the 1950s were more overtly apocalyptic than those of later years, and as for Catholic preachers of the time, the total evil of Communism was taken for granted. In his famous 1949 crusade in Los Angeles, Graham had proclaimed that “Communism has decided against God, against Christ, against the Bible, and against all religion. . . . Communism is a religion that is inspired, directed and motivated by the Devil himself, who has declared war against Almighty God.” Or this from 1953: “Either Communism must die, or Christianity must die, because it is actually a battle between Christ and Anti-Christ.”

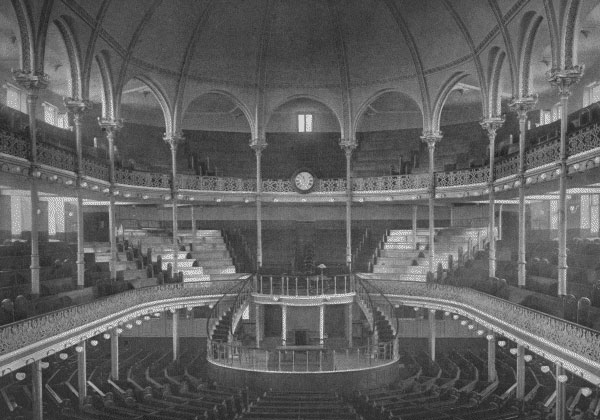

His Pittsburgh crusade of 1952 coincided with the public panic over so-called “hell-bombs”—hydrogen bombs—and of nuclear warfare more generally. (The first full hydrogen bomb test would occur in November 1952, but the concept had been widely discussed for some years, and there had been several partial tests). Graham consistently presented world-events in this eschatological framework. He declared that “All of the trouble with Russia began in the Garden of Eden.” Only a religious revival could prevent what was ultimately a spiritual rather than a political menace: “Unless this country has a revival of both morals and religion, it can’t survive the onslaught of Communism.”

Graham represented the apocalyptic strain in the evangelical approach to Communism, the diabolical inspiration of which was proved by the destruction of Christian missions in China and elsewhere. The imminence of the end times might well be signaled by historic events like the recent return of the Jews to the land of Israel—and of course, the development of larger and larger nuclear weapons. If you did not recognize that these were the end times, you weren’t reading the headlines.

Given Graham’s titanic status and manifest faithfulness to the Lord, it is tempting to see him as a man who transcended history. The essential message of the gospel does transcend history, but its messengers do not. It is probably more helpful—and even edifying—to realize that Graham’s remarkable evangelistic labors transpired within a specific historical context.

We’re all embedded in our cultural surroundings, which should make us cautious about combining current political controversies, even ones as serious as the threat of hydrogen bombs, with the message of salvation through Christ. The Cold War was just one of many facets of that context in which God blessed Graham’s transcendent message.