The average churchgoing evangelical has been one of the casualties of academic and journalistic studies of “evangelicals” in the Trump era. The obsession of the past half decade has been with the extreme Trumpian evangelical, especially the extreme Trumpian white pastor. The activities that normally define practicing evangelicals – worship, studying the Bible, missions, giving to Christian charity – have largely been set aside in favor of political sensationalism. In countless studies and stories on evangelicals, we usually get a menagerie of evangelical (or quasi-evangelical) exotics, those who make extreme statements on gender, or race, or vaccines, or Trump, or whatever else is required for the political controversy of the moment. And there are always evangelical leaders who are ready to supply ever-more radical commentary to keep the media interested, and progressives aggrieved.

The cumulative effect of this depressing pattern is that everyday evangelicals often don’t find much that’s immediately familiar in coverage of evangelicals. (Unless of course they watch Fox News or listen to talk radio or buy “evangelical” books from the airport newsstand.) When’s the last time you read something on evangelical pastors who handle politics in a thoughtful way? It’s like the proverbial evangelical tree falling in the forest. If it doesn’t cause a sensation or get reviled, does it still exist?

All this may help explain how refreshing it was to read Melanie Ross’s excellent Evangelical Worship: An American Mosaic (Oxford, 2021). As a member of a large evangelical congregation myself, there is much that is familiar, and much to ponder, in this challenging but empathetic study. Ross’s book also does something that almost no scholarly work on the history of evangelicalism ever does: discuss what happens in actual church services. As the great scholar of evangelicals David Bebbington has often noted, as central as church services are to evangelicals’ lives, the historical and anthropological evidence for what happens in those services – especially prior to the widespread recording of such services in the church website era – is vanishingly thin.

Ross is Associate Professor of Liturgical Studies at Yale Divinity School, and an expert on church hymnody, liturgical practices, the history of American worship. She comes out of an evangelical background herself. In her book, Ross reviews her own experience growing up evangelical, especially with regard to worship practices. She holds a view that I suspect is common among liturgical experts who are also practicing believers: ambivalence about the heightened commercialization of worship music, combined with a realization that churches to some extent have to cater to the musical tastes of their congregants. Ultimately God moves among people worshipping in Spirit and truth, regardless of the genre and musical accompaniment. But Ross doesn’t think that truth lets churches off the hook from taking their musical choices seriously.

Ross argues that the fading “traditional vs. contemporary” dichotomy of the worship wars – which was never as clear a distinction as polemicists suggested – is now settling into a “mosaic” model of worship styles, varying by congregations. Churches are not static; they are normally navigating tensions within the congregation itself with regard to worship practices. Still, she wants us to remember the treasures of the great tradition of evangelical hymnody. A generation that loses touch with that tradition is impoverished for it.

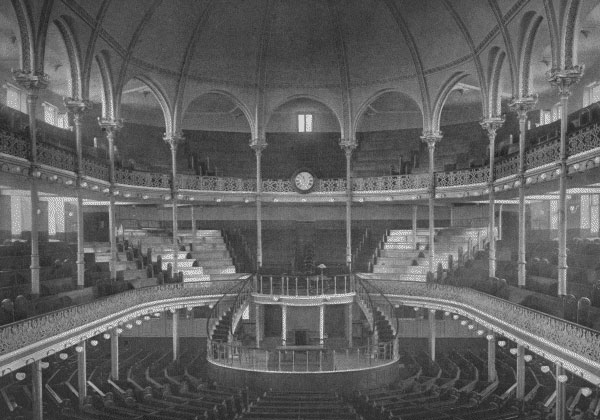

Ross surveys a range of evangelical congregations where she did field work and interviews, to get the texture of worship practices and competing views about worship styles and songs. Nearly all of her “evangelical” churches unquestionably fit that description, but they are largely nondenominational, urban/suburban, and usually connected to the historic evangelical or charismatic movements. Park Street Church in Boston, and Moody Church in Chicago, are her first two case studies: historic evangelical congregations, though not usual stops on the politicized menagerie tour. They’re also struggling with how to respect their evangelical traditions in music, while not coming off as stuffy or inflexible.

Instead of the strict traditional vs. contemporary dichotomy, Ross shows that recurring tensions over competing goods commonly play out within the same congregation. Often large congregations have a worship minister who worries about the ahistorical, commercialized nature of worship music. But the minister knows there are limits about how much one might wisely fight against the tide of popular taste.

Another key tension is how much congregational participation in singing is expected. At Moody Church, the music minister overtly trains the congregation in the basic practices of choral singing. At North Point Church in Atlanta, the ministerial team cranks up the music so loud that you can’t hear yourself singing anyway, and it puts no expectation on anyone to sing, lest any visiting seekers feel uncomfortable. But this practice bothers some of the worship staff at North Point, one of whom complains to Ross about how many attendees just stand silently during songs, starting blankly at the stage while holding a Starbucks cup.

In some chapters, music fades into the background as Ross tackles difficult congregational questions such as racial inequality and ethnic violence. Such matters are actually not incidental to worship music, especially in more charismatic settings (like a pseudonymous Vineyard congregation she visited on the West Coast) where music leaders also have significant praying and speaking roles. Ross notes that she visited the Vineyard church shortly after the 2016 killings of Alton Sterling and Philando Castile. Machelle, one of the only black members of the congregation, was also a music leader. The church dealt awkwardly with the news of the killings, reflecting the classic dilemma of what political and cultural issues deserve direct mention during a worship service. Machelle regarded her nearly all-white church as “vague and unclear” in its response to police violence against black men.

Ross includes a chapter on a pseudonymous “emergent” church in Portland, which charmingly posted a “No Smoking or Consuming Cannabis Inside” sign at the entrance to its rented warehouse. This is a useful examination of the challenges facing emergent churches circa 2016, but it is perhaps the chapter that seems the most passé now. One suspects that most emergent churches have either closed, abandoned the emergent model, and/or fully embraced progressive theology in the past decade, so I found myself wondering about the ongoing pertinence of the emergent movement within the “evangelical” mosaic.

Conversely, perhaps the most rewarding section of the book is Ross’s analysis of Keith and Kristyn Getty’s music ministry. Theirs is perhaps the epitome of the evangelical mosaic’s impulse to offer music that seems affective and relevant, while also tapping into the treasures of the historic tradition. Those (like me) who don’t have formal musical training might get a little lost in the details in this section, but the Gettys (and apparently Ross) are convinced that composers and songwriters can identify qualities in melody and lyrics that make a song enduring, and transmissible across time and culture.

Kristyn Getty specifically cites “Be Thou My Vision” as an example of a Christian song that works with almost any (competent) musical accompaniment, or none at all. The Gettys are helping a new generation of worship leaders to lead churches in songs that have that enduring quality, both musically and theologically. “Enduring,” in this way of thinking, is far preferable to “current.”

I am only scratching the surface here regarding the rich detail that Ross’s book reveals about evangelical worship culture in the U.S. (One can only imagine the rich analysis one could undertake for the similar vibrant but contested cultures of the evangelical worlds of Brazil, Nigeria, China, and more.) The conclusion one reaches in reading this profound analysis, however, is that “worship” is bigger, more complex, and more important to a Christian’s identity than most evangelicals or scholars of evangelicals knew.

It’s also far more complicated than the old “traditional vs. contemporary” wars, which are now passing from the scene. In Ross’s analysis, “worship wars” was never really the right way to frame it anyway. To Ross, “evangelical worship is best understood as a theological culture that must continually negotiate the paradoxes of continuity and change, consensus and conversation, and sameness and difference.” Want to understand what she means, and how it applies to your congregation? Read Professor Ross’s outstanding book.