Phillis Wheatley, the first published African American female poet and a devout Christian, died on December 5, 1784. We can’t be sure of her birthdate, because she was born in West Africa and sold into slavery by 1761. This is from her profile at the Poetry Foundation:

Recent scholarship shows that Wheatley wrote perhaps 145 poems . . . but [much of] this artistic heritage is now lost. . . . Of the numerous letters she wrote to national and international political and religious leaders, some two dozen notes and letters are extant. As an exhibition of African intelligence, exploitable by members of the enlightenment movement, by evangelical Christians, and by other abolitionists, she was perhaps recognized even more in England and Europe than in America. Early 20th-century critics of Black American literature were not very kind to Wheatley because of her supposed lack of concern about slavery. Wheatley, however, did have a statement to make about the institution of slavery, and she made it to the most influential segment of 18th-century society—the institutional church.

Two of the greatest influences on Phillis Wheatley’s thought and poetry were the Bible and 18th-century evangelical Christianity; but until fairly recently Wheatley’s critics did not consider her use of biblical allusion nor its symbolic application as a statement against slavery. She often spoke in explicit biblical language designed to move church members to decisive action. For instance, these bold lines in her poetic eulogy to General David Wooster castigate patriots who confess Christianity yet oppress her people:

“But how presumptuous shall we hope to find

Divine acceptance with the Almighty mind

While yet o deed ungenerous they disgrace

And hold in bondage Afric: blameless race

Let virtue reign and then accord our prayers

Be victory ours and generous freedom theirs.”

And in an outspoken letter to the Reverend Samson Occom, written after Wheatley was free and published repeatedly in Boston newspapers in 1774, she equates American slaveholding to that of pagan Egypt in ancient times: “Otherwise, perhaps, the Israelites had been less solicitous for their Freedom from Egyptian Slavery: I don’t say they would have been contented without it, by no Means, for in every human Breast, God has implanted a Principle, which we call Love of freedom; it is impatient of Oppression, and pants for Deliverance; and by the Leave of our modern Egyptians I will assert that the same Principle lives in us.”

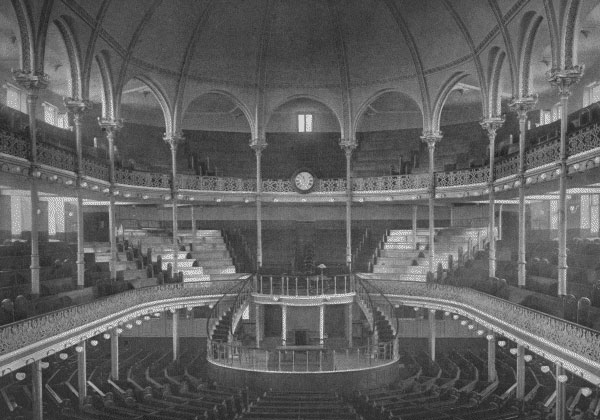

Wheatley’s most popular poem was her 1770 elegy to George Whitefield, who died in Massachusetts that year.

Hail, happy Saint, on thy immortal throne!

To thee complaints of grievance are unknown;

We hear no more the music of thy tongue,

Thy wonted auditories cease to throng.

Thy lessons in unequal’d accents flow’d!

While emulation in each bosom glow’d;

Thou didst, in strains of eloquence refin’d,

Inflame the soul, and captivate the mind.

Unhappy we, the setting Sun deplore!

Which once was splendid, but it shines no more;

He leaves this earth for Heav’n’s unmeasur’d height,

And worlds unknown, receive him from our sight;

There WHITEFIELD wings, with rapid course his way,

And sails to Zion, through vast seas of day.

Then she implored her fellow African Americans to accept Whitefield’s savior.

Take HIM ye Africans, he longs for you;

Impartial SAVIOUR, is his title due;

If you will chuse to walk in grace’s road,

You shall be sons, and kings, and priests to GOD.

A variant edition of the poem ended that line with, “He’ll make you free, and kings, and priests to God.” This undoubtedly reflected Wheatley’s desire for her fellow slaves.

Wheatley’s owners emancipated her in 1773. Wheatley married a free African American man, but their marriage was marked by poverty and suffering. Wheatley worked for a time as a maid in a boarding house before dying in obscurity in 1784. She was probably 31 years old. Evangelicals, of all people, need to remember her today.

For more on Phillis Wheatley, see Penguin Classics’ Phillis Wheatley: Complete Writings.