Today as tensions between North Korea and the U.S. reach heights not seen since the 1950s, it is easy to forget that northern Korea used to be one of the Asian strongholds of Protestant Christianity. As Atlas Obscura recently explained, the city of Pyongyang became known to missionaries as the “Jerusalem of the East.” The city had great institutional strength for Protestantism, including Union Christian Hospital, Union Presbyterian Theological Seminary, and Union Christian College, the first four-year college anywhere in Korea.

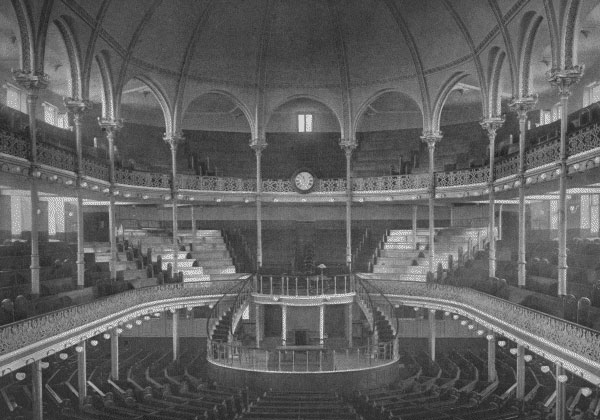

One hundred ten years ago, Pyongyang saw the outbreak of a massive revival, the high point of the season of evangelical strength in northern Korea. Presbyterian missionary William Blair preached to thousands of Korean men, focusing on their need to turn away from their traditional hatred of the Japanese people, with whom Korea had a long history of conflict. The missionaries and Korean Christians had been praying for an outpouring of the Holy Spirit for revival and repentance, and it came on that Saturday night in January 1907. Many at the meeting began praying out loud, and soon the signs of awakening began to appear. As one missionary described it, the sound of many praying at once brought

not confusion, but a vast harmony of sound and spirit, a mingling together of souls moved by an irresistible impulse of prayer. The prayer sounded to me like the falling of many waters, an ocean of prayer beating against God’s throne. It was not many, but one, born of one Spirit, lifted to one Father above. Just as on the day of Pentecost . . . God is not always in the whirlwind, neither does He always speak in a still small voice. He came to us in Pyongyang that night with the sound of weeping. As the prayer continued, a spirit of heaviness and sorrow for sin came down upon the audience. Over on one side, someone began to weep, and in a moment the whole audience was weeping.

Man after man would rise, confess his sins, break down and weep, and then throw himself to the floor and beat the floor with his fists in perfect agony of conviction. My own cook tried to make a confession, broke down in the midst of it, and cried to me across the room: “Pastor, tell me, is there any hope for me, can I be forgiven?” and then threw himself to the floor and wept and wept, and almost screamed in agony. Sometimes after a confession, the whole audience would break out in audible prayer, and the effect of that audience of hundreds of men praying together in audible prayer was something indescribable. Again, after another confession, they would break out in uncontrollable weeping, and we would all weep, we could not help it. And so the meeting went on until two o’clock a.m., with confession and weeping and praying.

Contrition over sin and praying out loud were among the distinguishing signs of this revival, which resulted in many new conversions and additions to church memberships.

Some observers later criticized the North Korean revival for its Pentecostal characteristics, and some have observed that the revival had strong syncretistic overtones that drew from Korean shamanist religion. There were surely some excesses, for what revival does not run to some extremes? But in general, the focus on grief and confession of sin—the sin of ethnic hatred, in particular—suggests to me that this was a revival in which the Spirit was indeed moving.

Although the seminaries and colleges did begin to raise up a strong contingent of native Korean leaders, the Christian community in Korea still depended a great deal on western missionary leaders. As World War II loomed, the Western powers began to withdraw all missionaries. At the end of World War II, the Korean peninsula was freed from Japanese occupation, but the Allied Powers agreed to split the peninsula into spheres of Western influence (South Korea) and Soviet communist influence (North Korea). The communist north became officially atheist, and has ruthlessly persecuted its remaining Christian community ever since.

So much news out of North Korea today focuses on their efforts to develop nuclear weapons and missiles, and on the instability of their leader, Kim Jong Un. But this revival of a 110 years ago reminds us of a different North Korean past. We should pray that God would bring both revival and religious freedom once again to the North Korean people.

See also Young-Hoon Lee, “Korean Pentecost: The Great Revival of 1907,” and Christianity Today‘s coverage of the 100th anniversary of the revival in 2007.

Sign up here for the Thomas S. Kidd newsletter. It delivers weekly unique content only to subscribers.