In this post I am interviewing Dr. Bruce Gordon about his new biography, Zwingli: God’s Armed Prophet (Yale University Press). Dr. Gordon is the author of many books on the Reformation, and is Titus Street Professor of Ecclesiastical History at Yale Divinity School.

[TK] You write that in studies of the Reformation, “Zwingli has long been cast as a lesser man than Martin Luther and as the warm-up act for John Calvin.” You argue, however, that “neither view stands up to scrutiny.” How should we think about Zwingli’s role in the Reformation?

[BG] Huldrych Zwingli is largely forgotten for two reasons. First, as a contemporary of Martin Luther he remains largely overshadowed by the German reformer. Traditionally, the focus has almost exclusively been on their debate over the Lord’s Supper, and Zwingli is usually characterized as having reduced the sacrament to a mere memorial meal.

Secondly, there is an assumption that anything significant from Zwingli was largely taken up and developed by John Calvin, who is regarded as the true founder of the Reformed tradition. Zwingli is seen as provincially Swiss while Calvin was the great international reformer. One consequence of these enduring perspectives is the virtual absence of Zwingli’s writings in good modern translations.

Among all of Zwingli’s intellectual influences, none was more important than the Dutch humanist and biblical scholar Desiderius Erasmus. What was it about Erasmus that made such a profound impact?

As a young priest Zwingli idolized Erasmus for his belief that the study of the classics was crucial for the reform of Christianity. Zwingli was a zealous student of Greek and Latin literature as well as of the Bible. He embraced Erasmus’ call to read the Bible in the original languages and to the study the works of the church fathers – many of whom Erasmus edited. Zwingli was also deeply influenced by Erasmus’ position on the symbolic nature of the sacraments and his emphasis on the imitation of Christ in the sanctified life. Although their friendship broke down, Zwingli never lost his admiration for the Dutchman.

How did Zwingli end up in Zurich, and how did the Reformation unfold in that city?

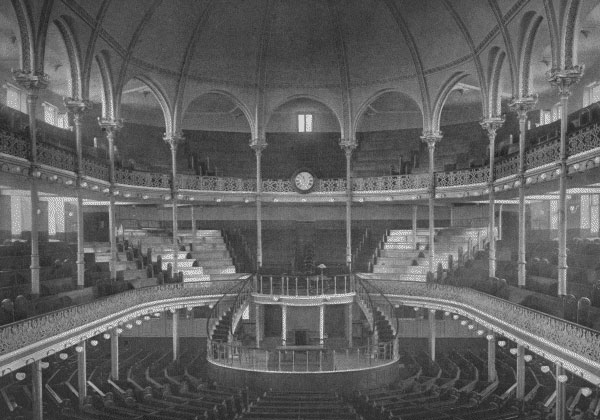

By 1518 Zwingli had an established reputation as a preacher. He was priest at a monastery in Einsiedeln, to which many of the leading families of Zurich came on pilgrimage. Zwingli was ambitious and wanted to come to Zurich as a priest and worked hard to be elected. He began his preaching in the Grossmünster – the principal church in Zurich – in January 1519. He immediately introduced a new form of sermon. Instead of using the lectionary he began with the first chapter of the Gospel of Matthew and preached through the whole book. The people should hear the whole Word of God. He did the same with the Old Testament.

Zwingli’s preaching was the catalyst for the Reformation in the city. His sermons also addressed the Christian life, and that included social and political issues, above all the mercenary service. God demanded repentance and renewal. Zwingli declared mercenary service an offense against God and denounced what he saw as moral corruption. His preaching inspired groups of figures to study the Bible and supporters for reform grew in Zurich around Zwingli. Zwingli’s preaching and the influence of Luther’s teaching on justification proved powerful. Following Erasmus, Zwingli became skeptical about many teachings of the Roman Catholic Church, such as the intercession of the saints. He was supported by key members of the ruling Council, enabling his reform ideas to gain political support.

By 1522 he was publicly confronting the church hierarchy on questions of the freedom of a Christian and clerical celibacy. He staged two public disputations in 1523 under the authority of the Zurich council at which his ideas became more radical. The only authority of the church should be the Bible; there was no need for bishops and hierarchy, and the mass was an abomination. Again, the support of influential families in the city made his agenda possible. There was enormous opposition from Catholics on the one side and, on the other, from the radicals (mostly former friends), who thought he had not gone far or fast enough.

In 1524 by order of the council, churches were stripped of all art and religious objects and their walls were whitewashed. At Easter 1525 the Reformation was formally instituted with abolition of the mass and the celebration of a new Reformed order of the Lord’s Supper. Zurich had formally left the Roman church.

Readers familiar with Reformation history may recall that Zwingli and Luther disagreed vehemently about the nature of the Lord’s Supper. Why was Zwingli’s “symbolic” view seen as so provocative?

Far more emphatically than Luther, Zwingli denounced the Catholic mass as an abomination. His chief argument was that priests were repeating the sacrifice of Christ on the altar. That sacrifice, he argued, had been offered once and was wholly sufficient. It was blasphemous to claim any need to reenact it. That would deny the efficacy of Christ’s death on the cross and resurrection.

Further, the bread and wine could not become the body and blood of Christ because the Son of God was no longer physically in the world. The Creeds made absolutely clear that he sits at the right hand of the Father. He is present in the world spiritually. Therefore, the Lord’s Supper must be a spiritual meal in which through faith Christians are united with Christ.

Zwingli’s ideas were heresy for Catholics who claimed he was denying the traditional teaching of the Church. Rejection of the mass was denial of the heart of Christianity. Martin Luther saw Zwingli as denying Christ’s own words when he said, “This is my body.” Zwingli claimed that Christ meant, “This signifies my body.” For Luther this was a perversion of the Gospel and demonstrated that Zwingli and his followers were “fanatics.” Luther argued that Christ meant that “is” means “Is” and that he is physically present in the sacrament. For him, there could be no compromise with Zwingli. They met once at Marburg and could not agree on the sacrament and remained hostile to one another.

Zwingli’s life came to an abrupt conclusion, as he died in battle in 1531. You say that he perished as a “casualty of his own willingness to use force to religious ends.” What accounts for the literal combativeness of Zwingli’s last years?

Although he is usually associated with the city of Zurich, that was never Zwingli’s perspective. He believed that the whole Swiss people had been called by God to embrace the Gospel. He saw himself as a prophet in the tradition of the Old Testament summoned to preach the Bible and ensure that all people heard God’s Word. From the time of his arrival in Zurich at the end of 1518 he understood that reform of the faith was not possible without the support of temporal authority. He made no distinction between the religious and the political, and his vision of the godly community was based on ancient Israel: king and prophet presiding over the whole community.

Zwingli understood the church to embrace the whole visible community, believers and unbelievers. There were two forms of righteousness, divine and human. The prophet declared God’s righteousness and called the people to follow Christ. The magistrates ruled by laws necessary to govern the community, implementing just governance and punishing offenders. The two spheres were closely related but distinct. In that sense, Zwingli’s Reformation always had a strong political character. The magistrates carried God’s will through just rule of the state while the prophets declared God’s Word and admonished the rulers when they failed in their duties. It was not a theocracy as the clergy did not control government.

Zwingli’s vision of the godly community, as I say, was envisaged for all the Swiss, but he believed that God’s Word was being thwarted by supporters of the Catholic Church and of the mercenary service. His conviction was that if the people were exposed to the preaching of Scripture they would be converted. He increasingly came to the conclusion that the opponents of the Gospel, as he saw them, could only be overcome by force. The magistrates should take up the sword to further the true religion.

He devised military plans by which Zurich and her allies to break the Catholic forces and establish preaching. By 1531 he had become wholly convinced that this was the only way and that if they failed the Reformation failed. Many of his colleagues were worried by his bellicose tendencies. Zwingli’s decision to support armed conflict proved his downfall as he fell in battle in October 1531.