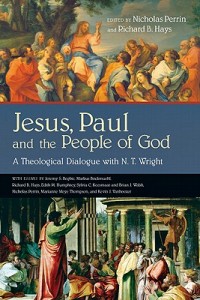

In the Spring of 2010, the Wheaton Theology Conference brought together a number of Christian scholars to assess the work of N.T. Wright, particularly in regards to his books on Jesus and Paul. The conference title, “Jesus, Paul, and the People of God”, indicated the framework for the two-day event: one day on Jesus, one day on Paul, and all of the talk was tied to how theology influences the people of God. Wright himself was present and was given the chance to respond to the other participants.

In the Spring of 2010, the Wheaton Theology Conference brought together a number of Christian scholars to assess the work of N.T. Wright, particularly in regards to his books on Jesus and Paul. The conference title, “Jesus, Paul, and the People of God”, indicated the framework for the two-day event: one day on Jesus, one day on Paul, and all of the talk was tied to how theology influences the people of God. Wright himself was present and was given the chance to respond to the other participants.

Nicholas Perrin and Richard Hays have incorporated the papers and Wright’s responses into a new book, Jesus, Paul and the People of God: A Theological Dialogue with N. T. Wright (IVP, 2011). The book attempts to analyze and critique Wright’s historical work, particularly as it relates to Christian theology. Though all the contributors are sympathetic to Wright’s vision, they refrain from merely praising his accomplishments and choose instead to honor him by offering a robust critique of some of his most prominent ideas.

Today and tomorrow, I will provide a review of this new book. First, we’ll look at the four essays that deal with Wright’s view of Jesus. Tomorrow, we’ll look at the essays that critique Wright’s work on Paul. My goal is to briefly summarize each essay and then offer a few reflections of my own.

N.T. Wright and the Historical Jesus

The first essay comes from Marianne Meye Thompson: “Jesus and the Victory of God Meets the Gospel of John.” Thompson focuses on a troubling inconsistency in Wright’s work. Wright believes in the historicity of John and has called for scholars to “discard the century-old shibboleths” that label John as non-historical. Still, Wright bases his reconstruction of the historical Jesus on the Synoptic witness alone, which leads Thompson to explore the ways in which John’s “Jesus” lines up with the “Jesus” presented in Wright’s work. She asks great questions:

- “Do we omit the Fourth Gospel in such discussions because it would somehow be taken to compromise any historical reconstruction?”

- “If John and JVG often make strikingly similar judgments about Jesus’ mission and accomplishments, what shall we conclude about either one?”

- “And does John’s approach to understanding Jesus suggest that we ought to rethink how Jesus is known ‘historically’?”

I believe Thompson’s critique of a John-less Jesus and the Victory of God to be valid. I understand that Wright wishes to play on the field of skeptical scholarship. He responds:

“Had I brought John into the equation without comprehensive justification, my principal conversation partners would have ignored the book.” (63)

Fair enough. But maybe the time is ripe for such “comprehensive justification” in the wider academy. Who better to make the case than N.T. Wright? As it stands, Jesus and the Victory of God, while commendable in so many ways, is of limited value for evangelical Christians because of John’s absence. Thompson is correct, however, to note the similarities between the Jesus we find in John and the Jesus we see in Wright’s work.

—–

Richard B. Hays offers an essay titled “Knowing Jesus: Story, History and the Question of Truth.” Hays offers the most strident critique of Wright’s work. He zeroes in on the question of truth and its relation to story and history. He seeks to establish clear roles for the Scriptural canon and church tradition in the hermeneutical task. The problem with Wright’s work, according to Hays, is that despite clear affirmations regarding the complementary nature of theology and history, Wright frequently suggests that the church’s faith obscures real history. Hays writes:

“Christian theological tradition is by and large bracketed out – at least at the explicit level – in Tom’s treatment of the evidence.” (51)

“Experience and critical history rescue us from the misreading of Jesus bequeathed to us by the church.” (51)

Hays believes that Wright shares many of the assumptions of the “historical Jesus” questers he is seeking to critique. It is Hays’ attempt to move beyond these assumptions that leads to this essay criticizing Wright’s methodological approach. Hays is concerned that Wright’s reconstructed Jesus results in a loss of each Gospel writer’s individual voice. He also notices Wright’s tendency to over-systematize everything through the framework of the “exile and return.” But it appears Hays’ biggest issue is that Wright sees the confessional tradition as a hindrance rather than an aid in discovering the biblical Jesus.

The two ways of studying Jesus come to the forefront in this summary from Hays:

“On the one hand, Tom insists that without historical investigation of the factuality of the Gospels, the story is vacuous, not least at the level of concrete action in the world. I insist, on the other hand, that without the canonical form of the story, we could never get the historical investigation right in the first place.” (61)

Of these four essays on Wright’s “Jesus,” Hays’ is the most important because it goes to the very heart of the presuppositions and assumptions that undergird the foundation of Wright’s work. From my perspective, I suspect that Wright and Hays are back to back fighting off opposing enemies. Wright is not setting a dichotomy between history and canon, but between a “kingdom-less” reading of the Gospels that fails to take into the historical truth already there in the canon. Hays is not saying that history matters less than the witness of the church, only that a resurrection-shaped lens of history necessarily shapes our presuppositions and approach to historical study.

—–

I won’t spend much time on Sylvia Keesmaat and Brian Walsh’s dialogical essay, “Outside the Circle of Friends: Jesus and the Justice of God.” Though creatively delivered, it is the weakest in the book. Keesmaat and Walsh take Wright to task for not situating the ethics of Jesus and the Victory of God more forcefully in the economic setting of the first century. Though Keesmaat and Walsh believe Wright has missed the focus on social justice in the Gospels, they are guilty of the opposite error: they find this emphasis everywhere.

The best example is their imaginative (I would even say “fanciful”) interpretation of the Parable of the Talents. According to Keesmaat and Walsh, the villain is the master, and the hero is the man who buried the money. Of the traditional interpretation, they write: “Our economic assumptions have dictated the hero of this story for us.” (81) Really? It’s more likely that Keesmaat and Walsh’s assumptions have dictated who they see as the hero. Otherwise, why are the earliest interpretations of the parable along the lines of Wright and the traditional view?

—–

Nick Perrin’s essay, “Jesus’ Eschatology and Kingdom Ethics: Ever the Twain Shall Meet” seeks to point out a blind spot in Wright’s proposal. Perrin believes that Wright emphasizes corporate application of Jesus’ commands to the exclusion (or diminishment) of individual ethics. Although Wright maintains that Jesus’ command to repentance has both a corporate and personal application, Wright most often states the corporate application. Perrin writes:

“Unlike the scriptural prophets, who as far as I can tell used the term repentance to indicate Israel’s duty to forsake a broad range of sins… Tom’s Jesus employs repentance in a specialized sense, by which he focuses his call very specifically on the issue of Israel’s violent militancy.” (107)

I believe Perrin’s critique to be spot-on. We can certainly be grateful for Wright’s reminder that repentance in the first century cannot be reduced to the lone individual feeling sorry for his sin. But to downplay or neglect the truth that Jesus’ call to repentance did indeed focus on the individual and every area of one’s life (not just nationalistic zeal) is misleading. So should we choose between a collective ethic and an individualist one? Perrin answers:

“It is only in correlating the individual and the corporate, the true Israelite and the true Israel, with reference to the resurrected future, that both of these attain their proper creationally ordered place and the extremes are finally transcended.” (112)

—–

The final essay in the section on Jesus comes from Wright himself: “Whence and Whither Historical Jesus Studies in the Life of the Church?” Instead of posting a lengthy review of this essay, I’d like to quote one of the sections in which you can see the basic outline of why Wright thinks the way he does. This paragraph illuminates the motivation for Wright’s historical work, and it explain why so many evangelicals (like myself) have found his work on Jesus and the resurrection to be helpful in many ways:

“Remember the slogan of Melanchthon in the sixteenth century: it isn’t enough to know that Jesus is a Savior; I must know that he is the Savior for me. I agree with Melanchthon, but I think we have to say it the other way round as well. We must today stress that it isn’t enough to believe that Jesus is “my Savior” or even “my Lord”; you must know who Jesus himself was and is. Without that, merely saying that we have Jesus “within our heart” or that we “have a sense that Jesus loves me” or whatever can easily turn into mere fantasy, wish fulfillment. That has happened before, and it will happen again, unless it is earthed in actual historical reality.

In order to know that you’re not just making it up, not fooling yourself… you must be able to say that this Jesus, who we know in prayer, this Jesus we meet when we are ministering to the poorest of the poor, this Jesus we recognize in the breaking of the bread, this Jesus is the same Jesus who lived and taught and loved and died and rose again in the first century. We must believe and confess that he did indeed inaugurate God’s kingdom, die to bring it about and rise again to launch the consequent new creation. We must know who Jesus himself actually was and is.

“Generations of skeptics have swept Jesus aside in their efforts to prove that Christianity is a dangerous delusion. Richard Dawkins is only one of many examples. We have to be able to provide proper, well-grounded answers.” (119)

This paragraph shines light on the area I believe Wright’s work to be most useful: apologetics. Wright wants to provide proper, well-grounded answers to the skeptics who dismiss Jesus and the Christians who don’t know much about him. Furthermore, he wants to make sure that the Jesus of history and the Christ of faith are one and the same. Noble goals, even if Wright doesn’t always attain them.

Tomorrow, we’ll look at how these scholars assess N.T. Wright’s “Paul.”