Where should we start when considering Gilbert Keith Chesterton?

I struggle to describe him, beyond the general description of “writer.” He wrote works of philosophy, apologetics, history, art and literary criticism, poetry, travelogues, novels, plays, detective stories, and thousands of essays. All in all, more than 15 million words in his lifetime. Where to start?

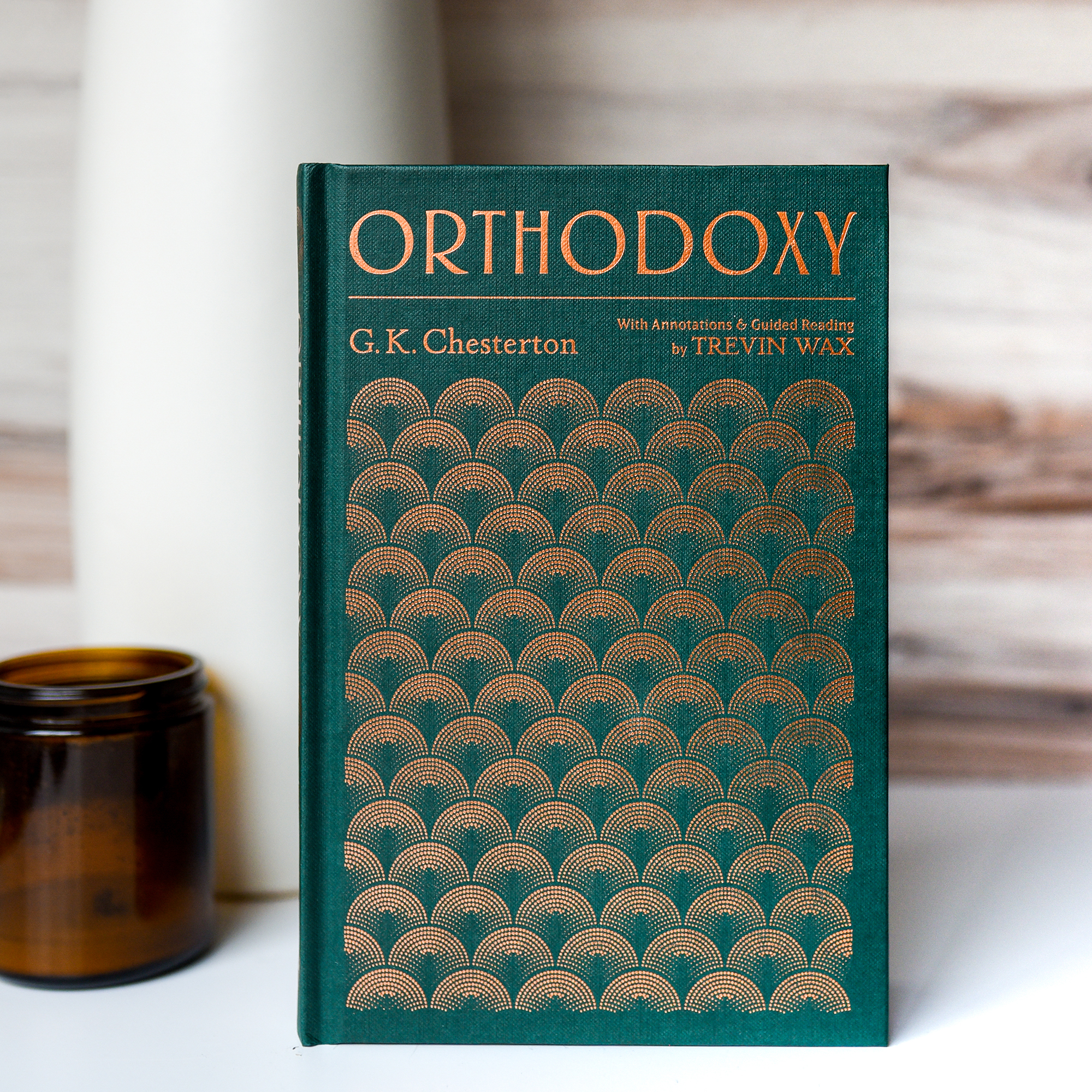

With Orthodoxy, of course. This is the best entry point into Chesterton’s work, especially if you’re most interested in Chesterton’s role as an apologist for the Christian faith. And today, I’m excited to announce the details of a new, beautifully designed edition of this classic book that incorporates my annotations, guided reading tips, and chapter summaries.

How Orthodoxy Came About

G. K. Chesterton’s parents were nominally religious, baptizing Chesterton as an Anglican although they held to Unitarian beliefs. Once Chesterton emerged from a period of pessimism in the late 1890s, his philosophy of life became increasingly visible in his writing. In the early 1900s, he took part in a long-running debate over religion with Robert Blatchford of The Clarion. The debate focused primarily on theism over against determinism; he did not delve into the particulars of the Christian creed.

In 1905, Heretics was released—a book that featured Chesterton interacting with many of the leading thinkers of his day. Heretics caused a stir, and one of the book’s reviewers issued a challenge: the writer claimed he would consider his own philosophy of life only if Chesterton was willing to disclose his. Chesterton had critiqued contemporary philosophies, but he hadn’t yet done the work of revealing his own. Orthodoxy was the book that came as a result, in 1908, when Chesterton was just 34 years old. It has never gone out of print.

I Can Help You Read Orthodoxy

Orthodoxy is not an easy book. One of the reasons it can be difficult is because of the historical and temporal distance between us and Chesterton. Unlike his initial readers, we’re not familiar with many of the people and places he mentions. But the biggest reason that Orthodoxy can be a challenge is that you are reading “one of the deepest thinkers who ever existed,” according to Étienne Gilson, the renowned Thomist scholar. Orthodoxy is a workout for the mind. You will walk away feeling worn out as well as invigorated. If at first you feel more of the former than the latter, you’re not alone.

The good news is, there’s no reason why Orthodoxy has to be harder to read than it should be. I’ve done what I can to lessen the more challenging aspects of this book.

Paragraph Breaks and Headings

For example, in line with the custom of the day, Chesterton wrote in lengthy paragraphs, sometimes spanning one or two pages. In order to enhance readability, I have inserted paragraph breaks and headings so that the flow of Chesterton’s argument becomes easier to discern. I have also updated the spelling in a number of instances.

Annotations

Throughout the text, I’ve added annotations that give more detail on the people, events, and Scriptural references Chesterton mentions. I sought to be more comprehensive than sparing in order to make the book more accessible to readers of all levels and backgrounds. My goal is to get you reading Chesterton without feeling so overwhelmed by his general knowledge and expertise that you give up.

As a side note, if you were to read articles or books on just the people Chesterton mentions in this book, you’d get a crash course in England’s history as well as the leading philosophies just before and after the turn of the 20th century. In this way, reading Chesterton is like entering a new world, or better said, it’s entering our world with a trustworthy guide whose knowledge covers the terrain of history, philosophy, and theology.

Introductory Remarks

My introductory comments for each chapter are designed to help you understand the lay of the land, so you can discern the pathways of Chesterton’s brilliant mind and be able to follow the argument. I leave a few “memorable parts to look for” at the outset as well, so that you’ll keep your eyes open for the most notable areas of Orthodoxy.

Chapter Summaries

At the end of each chapter, I summarize what Chesterton has said, in order to make it easier to move forward to the next chapter and not forget what has gone before.

Reflection and Discussion Questions

Like any exercise routine or mountain climbing endeavor, you’re better off enlisting a partner or two than trying on your own. For this reason, I’ve included discussion questions at the end of each chapter, so as to facilitate good conversation around the central aspects of Chesterton’s work.

Impact of Orthodoxy

C. S. Lewis loved Orthodoxy. “In reading Chesterton . . . I did not know what I was letting myself in for,” he wrote. “I had never heard of him and had no idea of what he stood for, nor can I quite understand why he made such an immediate conquest of me.” Lewis considered Chesterton’s The Everlasting Man to be “the very best popular defense of the full Christian position I know.”

H. L. Mencken, a public intellectual who vehemently opposed Christianity, acknowledged Orthodoxy was “the best argument for Christianity I have ever read—and I have gone through, I suppose, fully a hundred.”

Orthodoxy feels at times like a cross between looking for golden nuggets in a dense jungle and whirling around on a roller coaster. Enjoy the ride. Keep the treasure. You can find this new edition with my annotations and guided reading wherever books are sold: Amazon, Lifeway, ChristianBook, Barnes and Noble, Books a Million, IndieBound, and more.

If you would like my future articles sent to your email, as well as a curated list of books, podcasts, and helpful links I find online, enter your address.