History

Clearly all the events in Genesis long predate the time of Moses—this is so with the patriarchs (chs. 12–50) and much more so with the primeval period (chs. 1–11). Further, there are important parallels between chapters 1–11 and stories of ancient times from Mesopotamia (e.g., creation and flood). Since these stories are generally called “myths,” some suggest that this is the right category for the stories in chapters 1–11. Some even argue that the stories of the patriarchs are legends, with only a loose connection to actual people and events. In order to sort through these issues, the first question is whether Genesis claims to record “history.”

In order to address this issue, it is crucial to have a good, clear, and precise definition of “history.” In ordinary language, the word simply refers to an account of events that the author believes to have happened; in and of itself, the label “history” makes no comment about whether the account is complete, unbiased, free from divine activity, in strict chronological sequence, or with or without figurative and imaginative (sometimes called mythological) elements.

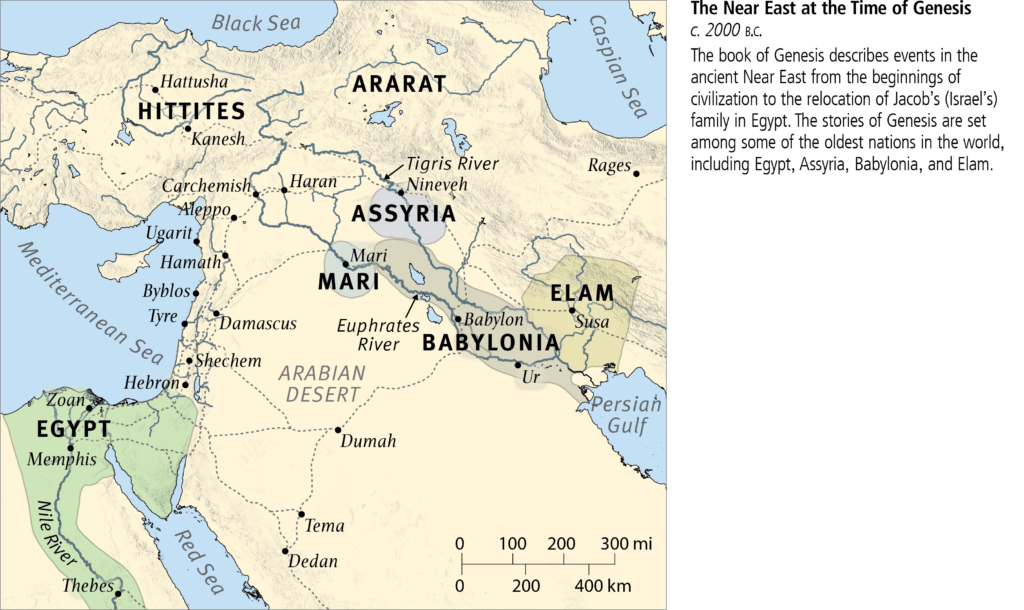

With this definition, it is easy to see that Genesis aims to record actual events rather than mythical events. The book explains to its Jewish audience how their ancestors came to be in Egypt; the genealogies connect Jacob and his children with the ancient generations, going back to Adam and Eve, the original pair of humans. Further, the book is narrative prose, whose main function in the Bible is to recount history. The creation account, Genesis 1:1–2:3, is stylistically different from the rest of the book; it is exalted prose, and its historicity is assumed elsewhere in the Bible (e.g., Ps. 136:4–9). (See Genesis and Science, below.)

The similarities of Genesis 1–11 to the Mesopotamian stories actually support the conclusion that these chapters intend to record history. The Mesopotamian stories clearly aim to celebrate actual historical events, but they do so in “mythological” terms. The Genesis stories are fundamentally different, however, in that they recount the activities of the one true God. Genesis, like the Mesopotamian stories, provides the opening act of a grand narrative that conveys a particular worldview. In order to provide the necessary grounding for this worldview, the author needed to use real events (albeit theologically interpreted). In this way Genesis aims to provide a true record of these events, in harmony with the biblical worldview. That worldview includes the notions that Yahweh, the deity of Israel, is the universal Creator of heaven and earth, who made mankind to know and love him; that all mankind fell through the disobedience of Adam and Eve; and that God chose Israel to be the vehicle by which all mankind would receive the blessing of knowing the true God. Clearly, that worldview requires the events of Genesis to be historical.

At the same time, it is not possible to answer all questions arising from Genesis. For example, faithful interpreters of the book disagree on just how long Adam lived before Abraham, or even how long the creation period lasted (see Genesis and Science, below). There is not enough material here for a complete life of Abraham. Even the name of the pharaoh that Joseph served is not mentioned. It is possible through archaeological research to locate some of the Genesis events in ancient Near Eastern history, at least in order to offer a plausible scenario for them. But it remains true that Moses has not sought to provide a comprehensive retelling of ancient days; his purpose lay elsewhere.

Science

The relation of Genesis to science is primarily a question of how one reads the accounts of creation and fall (chs. 1–3) and of the flood (chs. 6–9). What kind of “days” does Genesis 1 describe? How long ago is this supposed to have happened? Were all species created as they are now? Were Adam and Eve real people? Are all people descended from them? How much of the earth did Noah’s flood cover? How much impact did it have on geological formations?

Faithful interpreters have offered arguments for taking the creation week of Genesis 1 as a regular week with ordinary days (the “calendar day” reading); or as a sequence of geological ages (the “day-age” reading); or as God’s “workdays,” analogous to a human workweek (the “analogical days” view); or as a literary device to portray the creation week as if it were a workweek, but without concern for temporal sequence (the “literary framework” view). Some have suggested that Genesis 1:2, “the earth was without form and void,” describes a condition that resulted from Satan’s primeval rebellion, which preceded the creation week (the “gap theory”). There have been other readings as well, but these five are the most common.

None of these views requires denying that Genesis 1 is historical, so long as the discussion in the section on Genesis and History is kept in mind. Each of these readings can be squared with other biblical passages that reflect on creation. The most important of these is Exodus 20:11, “in six days the Lord made heaven and earth, the sea, and all that is in them, and rested on the seventh day”: since this passage echoes Genesis 1:1–2:3, the word “day” here need mean only what it means in Genesis 1. Therefore, it does not require an ordinary-day interpretation, nor does it preclude an ordinary-day interpretation. The arguments for and against these different views involve detailed treatment of the Hebrew (going far beyond the question of the meaning of “day”), and assessing these arguments would go beyond the goal of this discussion.

A further question involves the genealogies: do they describe direct father-to-son descent, or do they allow for gaps? The Hebrew term “father” can be used of a distant ancestor, and “son” can refer to a distant descendant. Likewise, “to father” can mean “to become the ancestor of.” In other words, the conventions for Hebrew genealogies allow for gaps; genealogies are not given to indicate a length of time.

These issues become less pressing when it is recalled that no biblical passage ever actually purports to count up the length of the creation week (outside of Ex. 20:11) and that no biblical author adds up the life spans in the genealogies to compute absolute time.

Should Genesis 1 be called a “scientific account”? Again, it is crucial to have a careful definition. Does Genesis 1 record a true account of the origin of the material universe? To that question, the answer must be yes. On the other hand, does Genesis 1 provide information in a way that corresponds to the purposes of modern science? To this question the answer is no. Consider some of the challenges. For example, the term “kind” does not correspond to the notion of “species”; it simply means “category,” and could refer to a species, or a family, or an even more general taxonomic group. Indeed, the plants are put into two general categories, small seed-bearing plants and larger woody plants. The land animals are classified as domesticable stock animals (“livestock”); small things such as mice, lizards, and spiders (“creeping things”); and larger game and predatory animals (“beasts of the earth”). Indeed, no species, other than man, gets its proper Hebrew name. Not even the sun and moon get their ordinary Hebrew names (Gen. 1:16). The text says nothing about the process by which “the earth brought forth vegetation” (Gen. 1:12), or by which the various kinds of animals appeared—although the fact that it was in response to God’s command indicates that it was not due to any natural powers inherent in the material universe itself.

This account is well cast for its main purpose, which was to enable a community of nomadic shepherds in the Sinai desert to celebrate the boundless creative goodness of the Creator; it does not say why, e.g., a spider is different from a snake, nor does it comment on what genetic relationship there might be between various creatures. At the same time, when the passage is received according to its purpose, it shapes a worldview in which science is at home (probably the only worldview that really makes science possible). This is a concept of a world that a good and wise God made, perfectly suited for humans to enjoy and to rule. The things in the world have natures that people can know, at least in part. Human senses and intelligence are the right tools for discerning and saying true things about the world. (The effects of sin, of course, can interfere with this process.)

It is clear that Adam and Eve are presented as real people. Their role in the story, as the channel by which sin came into the world, implies that they are seen as the headwaters of the human race. The image of God distinguishes them from all the animals, and is a special bestowal of God (i.e., not a purely “natural” development). It is no wonder that all human beings share capacities for language, moral judgment, rationality, and appreciation for beauty, unlike and beyond the powers observed in the animals; any science that ignores this fact does not faithfully describe reality. The biblical worldview leads one to expect as well that all humans now share a need for God and a bent toward sin, as well as a possibility for faith in the true God.

One must take similar care in reading the flood story. The notes will discuss the extent to which Moses intended to describe the flood’s coverage of the globe. Certainly the description of the flood implies that it was widespread and catastrophic, but there are difficulties in making confident claims that the account is geared to answering the question of just how widespread. Thus, it would be incautious to attribute to the flood all the geological formations observed today—the strata, the fossils, the deformations, and so on. Geologists agree that catastrophic events, such as volcanic eruptions and large-scale floods, have had great impact on the landscape; it is questionable, though, whether these events can in fact achieve all that might be claimed for them. Again, such matters do not come within the author’s own scope, which is to stress the interest that God has in all mankind.

Thus, even though it is wrong to use Genesis as if it were directly furnishing information in modern scientific form, it is nonetheless crucial to affirm its historical account and its God-centered worldview in order to provide a proper foundation for doing good science.