Themes

The theme of Numbers is the gradual fulfillment of the promises to Abraham that his descendants would be the people of God and occupy the land of Canaan. The book shows the reality of God’s presence with Israel in the cloud of fire over the tabernacle, but the repeated displays of unbelief by Israel delay the entry into Canaan and cost many lives. Nevertheless, by the end of the book, Israel is poised to enter the land.

The theme of the Pentateuch is the gradual fulfillment of the promises to the patriarchs, and Numbers makes a notable contribution to the exposition of that theme. There are four elements to the patriarchal promise set out first in Genesis 12:1–3: (1) land, (2) many descendants, (3) covenant relationship with God, and (4) blessing to the nations. These four aspects of the promise all play a role in Numbers.

- The land. The land of Canaan is the goal of the book of Numbers. It is broached in the first chapter, where a census is taken of all the men who are able to go to war. Israel is being prepared to fight for the land. Chapter 10 sees them setting out from Sinai, led by the fire of God’s presence. Chapter 13 relates their arrival at the southern border of the land and the mission of the spies. The spies’ gloomy report causes Israel to lose heart about the land, and God sentences them to wander for 40 years in the wilderness. But the second half of the book shows the people again on the move toward the land, overcoming opposition and reaching the eastern border of Canaan, marked by the Jordan River (ch. 34). The last word from God in the book is both a command and a promise: each of the tribes of the people of Israel shall hold on to its own inheritance (Num. 36:9).

- Descendants. Abraham had been promised that his descendants would be as many as the stars of heaven (Gen. 15:5). Jacob’s family consisted of just 70 persons when he entered Egypt (Gen. 46:27). Now they have increased immensely. The first census showed that the fighting men numbered 603,550. That did not include women and children. Surveying their camp from a hilltop, Balaam declared, “Who can count the dust of Jacob or number the fourth part of Israel?” (Num. 23:10). Balaam went on to predict that Israel would become a powerful kingdom in its own right: “a star shall come out of Jacob, and a scepter shall rise out of Israel” (Num. 24:17).

- Covenant relationship with God. The essence of the covenant was, “You shall be my people, and I will be your God.” The Lord’s presence with Israel is constantly brought out in the book of Numbers. There are the dramatic manifestations of his presence in the cloud that guided them or that appeared at moments of crisis (e.g., Num. 9:15–23; 14:10). Then the design of the tabernacle and the harsh measures to be taken against intruders all emphasized the reality of God’s holy presence (Num. 3:38). On the other hand, Israel was expected to trust God’s promises and obey his laws. Failure to do so resulted in death for the individual and sometimes for large groups (e.g., Num. 15:32–36; 25:6–9). Even Moses forfeited his right to enter the land because of disobedience (Num. 20:10–13). But despite Israel’s persistent failure to keep to the law, God never forsakes them or goes back on his promises. They may have to wait an extra 40 years to enter the land, but eventually they do reach it. “The Lord is slow to anger and abounding in steadfast love” (Num. 14:18).

- Blessing to the nations. This is the aspect of the promises that is least apparent in Numbers. To a greater or lesser degree, the nations that Israel encounters are all hostile: the Edomites refuse Israel passage; the Moabites try to have Israel cursed; Sihon and Og attack them and are defeated (chs. 21–22). Nevertheless Balaam recalls the phrasing of Genesis 12:3 when he says, “Blessed are those who bless you, and cursed are those who curse you” (Num. 24:9). The implication is that nations who treat Israel generously by blessing her will themselves be blessed.

Background

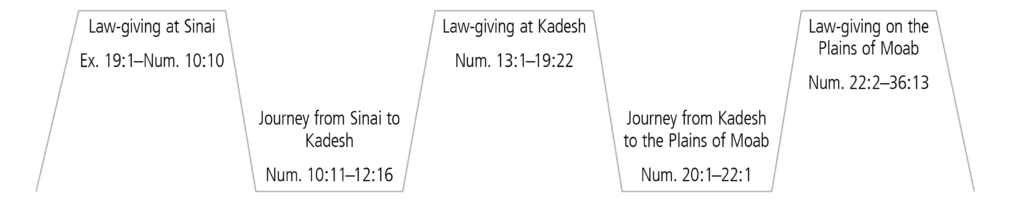

Jews refer to the first five books of the Bible as “the Law” (Torah), and Christians call them the “Pentateuch” or “The Five Books of Moses.” Numbers is the fourth volume in this series and relates Israel’s journey from Mount Sinai to the borders of the Promised Land, summarizing some 40 years of the nation’s history. The book begins with Israel making final preparations to leave Sinai. It then records their triumphal setting out, before relating a series of disasters in which the people grumbled about the difficulty of the journey and the impossibility of conquering Canaan. This response leads to God delaying the entry to Canaan by 40 years. The closing chapters of the book tell how the people at last set out again and reached the banks of the Jordan, poised to cross into the land promised to their forefathers.

Numbers thus relates a most important stage in the early history of Israel. Genesis begins with the creation of the world, but soon focuses on the life of the patriarchs and ends with their move to Egypt. Exodus tells how they left Egypt and came to Sinai to receive the law. Leviticus contains some of these laws, and Numbers still more. Numbers also summarizes the 40 years in the wilderness, and Deuteronomy (the sequel to Numbers) has Moses expounding the laws and urging the people to obey them. Deuteronomy ends with Moses’ death.

Another way of looking at the Pentateuch is as a biography of Moses (see ESV Study Bible, pp. 35–37). Numbers makes a vital contribution to this biography. First, it underlines Moses’ unique role as mediator between God and Israel. As elsewhere in the Pentateuch, it is constantly reiterated that “the Lord spoke to Moses.” And when this is challenged by his brother and sister, God himself intervenes: “With him [i.e., Moses] I speak mouth to mouth, clearly, and not in riddles, and he beholds the form of the Lord” (Num. 12:8). Second, it makes an astounding claim about Moses’ character: “Now the man Moses was very meek, more than all the people who were on the face of the earth” (Num. 12:3; see ESV Study Bible note on Num. 12:3–4). Third, it explains why Moses never entered Canaan himself : his failure to follow God’s instruction precisely is tersely told (Num. 20:10–13), as is the subsequent death of his brother Aaron for supporting Moses’ action (Num. 20:22–29). The book closes with the reader left in suspense about when and how Moses himself will die.

Numbers is to be classed as a historical work, not only because various details in it are corroborated by archaeological discoveries but also because it deliberately sets out to record what happened on the journey from Mount Sinai to the Jordan River. It does this to instruct future generations of readers with the lessons to be learned from the wilderness experience. It is saying in effect to the reader, “Your forefathers made many mistakes on their journey to Canaan; make sure you do not repeat them.”

However, Numbers does not paint an entirely gloomy picture: the book encourages its readers as well as warns them. By the end of the book the people of Israel have conquered formidable opponents in the Transjordan (the land east of the Jordan River), taken possession of their territory, and are poised to cross the Jordan and enter the Promised Land. In this way the book shows how the promises to the patriarchs are being fulfilled.

History of Salvation Summary

Numbers continues the story of God’s people, following them from Mount Sinai to the verge of the Jordan River. The book shows the steadfast purpose of God to fashion a people for himself who will display his image to the world, and out of which his appointed Savior will arise. The unfaithfulness of the members of that people puts God’s steadfastness to the test; but whereas the unfaithful members suffer God’s punishment, the people as a whole are preserved and shaped.

Taken from the ESV® Study Bible (The Holy Bible, English Standard Version®), copyright ©2008 by Crossway, a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers. Used by permission. All rights reserved. For more information on how to cite this material, see permissions information here.