Matthew Sutton has ambitious goals. It’s no overstatement to conclude that he intends to change the way historians, and observers of American religion and politics, understand the nature of evangelicalism and its shaping influence on our national life.

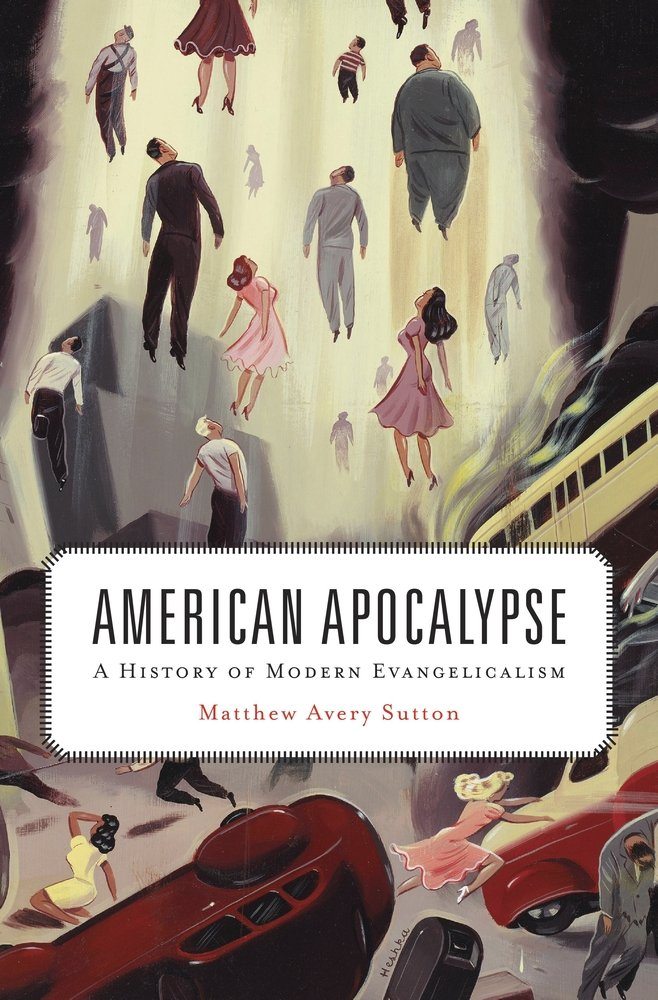

American Apocalypse: A History of Modern Evangelicalism proposes that many of the differentiations between “evangelicalism” and “fundamentalism” are artificially constructed, causing most historians to miss the fact that the entire tradition shares a premillennial expectation of an imminent and traumatic second coming of Christ. In this regard, Sutton, professor of history at Washington State University, tries to posit a category of “radical evangelicals” in the 20th century who often straddled the world of populist prophecy decoders and mainstream (predominantly white male) leaders of evangelical institutions, publications, and organizations. In his estimation, this central and driving insistence on premillennial apocalypticism set this group apart from a variety of other conservative Protestant groups. For those familiar with the literature on the subject, they will recognize Sutton’s thesis as a revision of longstanding dominant arguments from George Marsden and Joel Carpenter.

This book is ambitious at every level, not only proposing fresh perspectives and interpretations on the history of American evangelicalism, but taking into account nearly a century of historical development. The result is a sweeping narrative that tells a cohesive story but still manages to do justice to the many expressions of the evangelical movement and its constantly changing subculture.

Ironically Helpful

Ironically, Sutton’s research is especially helpful in areas where there’s little apparent tie to apocalypticism. For example, his account of the attitudes and responses of white evangelicals to the civil rights movement is one of the best short synopses I’ve seen anywhere. Sutton shows the deeply conflicted nature of evangelicalism’s response, documenting from primary sources how prominent white evangelicals, even while decrying racism in principle, often ended up giving de facto defenses of the racial status quo and condemning protests, boycotts, and nonviolent resistance as morally illegitimate options in the battle for justice.

American Apocalypse: A History of Modern Evangelicalism

Matthew Sutton

American Apocalypse is undergirded by exceptional work in primary source material, much of which has never been documented before. For example, Sutton includes a fascinating anecdote about an FBI investigation of R. A. Torrey for supposed un-American activities during World War I. Sutton represents the historian at his best—doing the hard work of archival research, submitting Freedom of Information Act requests, and looking in places others may have missed to get closer to the truth.

Not only is his research exemplary, but Sutton also writes with empathy, avoiding overly reductionistic or simplistic portraits. For example, in his chapter on the beginnings of the fundamentalist movement, he points out the nuanced role premillennialism played. On the one hand, it functioned as a proxy for a host of other “fundamental” doctrines of orthodoxy. Sutton presents the evidence in a compelling way to demonstrate how these early leaders identified apocalypticism as an indicator of theological fidelity concerning of a wide range of other doctrines. On the other hand, he’s careful to note premillennialism was also more than a proxy and shaped and influenced in real ways the lives of large numbers of Americans. Regarding the conflict between modernists and fundamentalists, he concludes:

The controversy revealed that fundamentalism was never simply about doctrine or subscribing to a series of essential beliefs. Countless Christians in the United States could affirm the “fundamentals.” The fundamentalist movement represented something else. It marked the rise of a network of apocalyptically oriented radical evangelical ministers, teachers, and radio personalities who insisted that the end was nigh and the apostasy predicted in Revelation had begun. (109)

Sutton’s narrative includes a good balance of sources that extend beyond the well-worn paths of the story of white evangelicals. Sutton brings black evangelical voices into the story in a way no other sweeping account of evangelicalism has before. When discussing the fundamentalist-modernist controversy, Sutton rehearses material that will be familiar to many, surveying the usual figures of the debate. But he also explores the ways in which “the nation’s black churches felt the effects of the controversy” (109).

One of Sutton’s most interesting arguments comes when he addresses the rise of postwar neo-evangelicalism and focuses on Carl Henry’s The Uneasy Conscience of Modern Fundamentalism (1947) in particular. Put succinctly, Sutton concludes, “Henry did bad history.” To be fair, Sutton is right to point out ways in which postwar figures like Henry were tempted to often overstate their differences with classic fundamentalism. But Sutton misses that their vision was different not only in its style and ambition, but also in its core principles. Sutton’s desire to locate apocalypticism everywhere as the uniting theme in American evangelicalism seems to render him at times blind to the diversity within the movement. For example, when discussing Henry and other neo-evangelicals he largely passes over the real distinction made over questions of separation. Whereas classic fundamentalists retained their insistence on second- and third-degree separation—refusing to collaborate with individuals and organizations who might have ties with others tied to groups like the National Council of Churches—Henry’s network had no appetite for such a tight drawing of lines.

Sweeping Account

In recent years, a spate of significant young historians have offered a range of excellent additions to the study of American evangelicalism. Some of the most notable of these have come from Darren Dochuk, Molly Worthen, and Daniel Williams. However, none of these has accomplished what Sutton has with American Apocalypse—a sweeping account of the entire span of 20th-century American evangelicalism that also resets prevailing scholarly assumptions and interpretations.

American Apocalypse will make a great many evangelical readers uncomfortable. Because of his extensive work in primary sources, Sutton has—better than anyone else—documented the ways in which some of the most prominent, and beloved, white evangelical and fundamentalist figures were enmeshed within their own cultural context. This enculturation manifested itself routinely in anti-Semitism, white supremacy, and nativism. Whether it’s reading Harold Ockenga’s anti-Semitic assessment of Jews in Hollywood, or the myriad of voices justifying white supremacy and indicting racial intermarriage, Sutton shows how these attitudes weren’t on the fringe of the movement. Rather, they often inhabited its center.

Sutton’s work effectively dismantles any sanitized memory of the period. And conservative evangelicals should be thankful. Sutton has done us a great service, reminding us that we construct our theologies in context. The church of Jesus Christ must be semper reformanda, always reforming. While culture, unjust structures, worldly prejudices, and false beliefs will always pollute our theologies, evangelicals are committed to testing all things by Scripture and, when proven wrong, humbly submitting to biblical authority.