For two of the three most influential Christian ministers of the 20th century, manner of death became central to their legacy. Felled by an assassin’s bullet in 1968, Martin Luther King Jr. (b. 1929) became a martyr to the cause of civil rights. Pope John Paul II (b. 1920) suffered publicly through various ailments until death ended his tenure in 2005. We cannot underestimate such open agony at the end of life, considering that his successor opted to retire in 2013.

The oldest of the trio, Billy Graham (b. 1918), recently turned 96. Unlike King, he will not likely die a martyr as he lives out his days in the family cabin near Montreat, North Carolina. Unlike John Paul II, he retains only nominal leadership responsibilities. Since the end of his public ministry in 2005, Graham’s influence has waned to the point where many 20-something evangelicals can’t identify him or else view him solely as a figure of distant history.

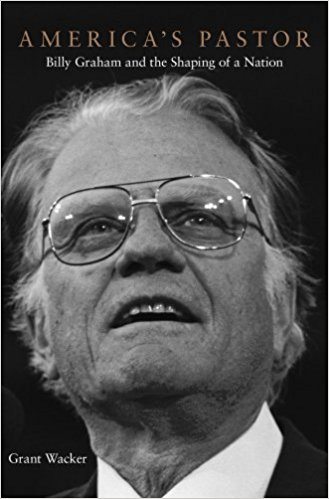

I don’t know how many of these young believers will pick up Grant Wacker’s new book, America’s Pastor: Billy Graham and the Shaping of a Nation. But I highly recommend they do so. Wacker, Gilbert T. Rowe Professor of Christian History at Duke University Divinity School, adds to the voluminous Graham literature with a scholarly yet captivating narrative that situates Graham alongside King and John Paul II as the men most responsible under God for shaping our current spiritual climate, especially in the United States.

America’s Pastor: Billy Graham and the Shaping of a Nation

Grant Wacker

Wacker covers much of the familiar ground with Graham. But his new book should not be seen as a substitute for William Martin’s A Prophet with Honor, the standard biography due for imminent re-release. Wacker, an acclaimed scholar and self-described “partisan” evangelical sharing Graham’s faith, seeks to answer two key questions: how does Graham’s story explain the unexpected growth of evangelical faith in America, and how does it illustrate the interplay between religion and American culture more generally? By the second page of the book Wacker projects his basic thesis: “[Graham] gave [Americans] tools to help them see themselves as good Christians, good Americans, and good citizens of the modern world at the same time.” Subsequent chapters explain how he did so as a preacher, icon, Southerner, entrepreneur, architect, pilgrim, pastor, and patriarch.

Long lauded for humility, Graham has confessed to many mistakes in his remarkable career. Yet as we’ll likely see with official tributes upon his death, nothing has tarnished his uniquely broad appeal. I would welcome additional clarification for his infamous interview with Robert Schuller, but his example of evangelism counters one strange interview about the uniqueness of Christ. He confused and even angered conservatives when he returned from his 1982 trip to the Soviet Union and noted the surprising religious freedom in the Communist country. But no one could object to his efforts to foster world peace and preach the gospel behind the Iron Curtain. Given the reputation of the late President Richard Nixon, Graham rightly regrets that he did not discern the depth of his close friend’s conspiratorial and paranoid tendencies, illustrated by lengthy Oval Office recordings of private meetings. Those recordings incited one of Graham’s most recent apologies, for disparaging remarks about Jews in the media. Because of his track record, many Jewish leaders forgave Graham for these remarks he does not remember offering. Wacker covers all these incidents with detail I had not previously seen in other works about Graham.

More importantly, Wacker uses these stories to identify the essential mystery with Graham: it’s not always easy to discern how much he shaped America and how much America shaped him. We claim to see clearly in retrospect how he traded access to the White House with such close friends and President Lyndon Johnson in exchange for supporting the widely discredited Vietnam War. But Graham is not so easy to dismiss as a sycophant. He resisted the rise of the Religious Right he unwittingly helped create with his evangelism, institution-building, fundraising, and public persona as chaplain to the stars, especially on 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue. He became less partisan as the country sorted in red states and blue states. Chastened by his public failures, he stepped back from politics just as many other pastors jumped in.

So who is the real Graham? Wacker wonders:

Which was normative, the savvy CEO or the simple preacher? The uptown sophisticate of the downhome country boy? The globetrotting absent father or the attentive family man? The name-dropping partisan of the White House or the humble servant of the church? Above all, the self-promoting entrepreneur or the self-effacing saint? (27)

Graham himself barely hints at this mystery with an aw-shucks tone and an unseemly penchant for name-dropping in his autobiography, Just As I Am. But Wacker aims to solve it. He writes, “From first to last, Graham displayed an uncanny ability to adopt trends in the wider culture and then use them for his evangelistic and moral reform purposes” (28).

I can’t argue with that clear, incisive summary. If the description fits Graham then it fits the evangelical movement he helped to carve out between fundamentalism and liberalism and led for about 50 years. We seek access to the halls of power, sometimes for our own glory. But we also want everyone from Wall Street to Main Street to hear the good news that Jesus can save people from their sins. Many of us come from humble backgrounds and preach that gospel with the hint of a Southern accent—not too much to alarm the elites, but not too little lest we be accused of forgetting our roots. We vote our values as responsible citizens. But we largely work within a system that eschews radicalism and frustrates bold efforts to address social ills.

We identify with Graham, because he is one of us, and he shaped us. As Wacker observes, “[Graham] possessed an uncanny ability to speak both for and to the times” (316). That’s why we evangelicals followed him for decades and why the world’s leading historians will continue to account for him long after we, too, have followed him to the far side banks of Jordan.