It’s no secret that an increasingly large portion of wealth in the United States belongs to a small number of people. Lest we simply write that off as “part of the deal” with capitalism and a global economy, economists and sociologists express great concern that pathways to economic mobility seem to be narrowing. Americans’ chances for financial stability depend more and more on being born and raised in a certain set of circumstances.

It’s becoming clear that the divides in our economic life also cut across our community life and relationships, even in the church. Christians in America often fear splitting into camps over political or moral issues. But are we in danger of sorting along economic lines—into one church for the wealthy and upwardly mobile, and another church for everyone else? One recent book sheds light on these divides and offers a subtle but striking corrective to our churches as well.

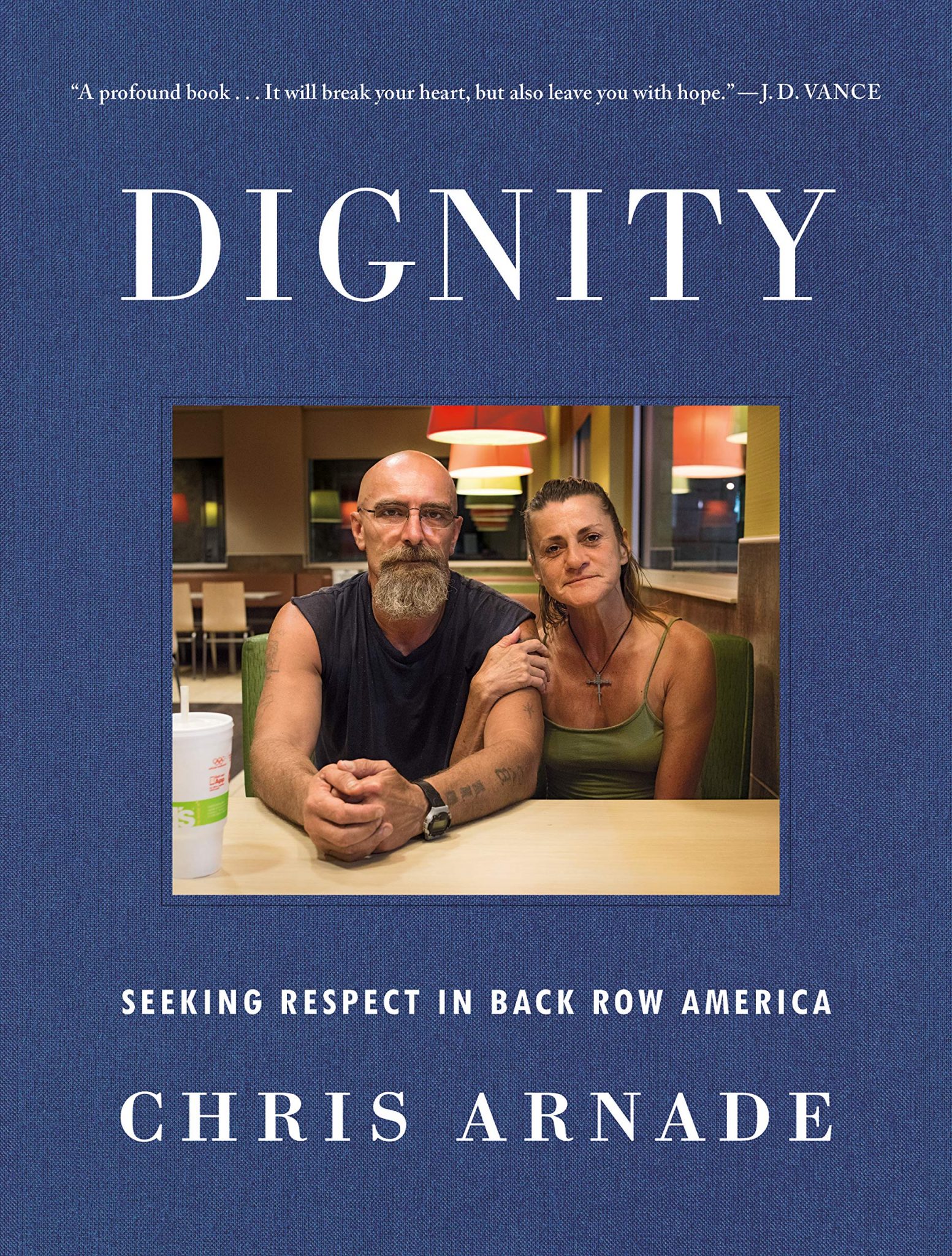

Chris Arnade’s Dignity: Seeking Respect in Back Row America hits nerves across the political and cultural spectrum with troubling observations. Here, through stories of people from various ethnicities and regions, we’re confronted with the fact that our systems haven’t resulted in “the American dream” for far too many. Historian Thomas Kidd called the book “the most sympathetic treatment of poor, broken Americans that I can recall ever reading.” Though coming from a professed non-believer and a mainstream publishing house, Dignity raises vital questions about how churches are failing to address the key concerns of many Americans—both in how we proclaim the gospel message and, more critically, in how our lives reflect what we profess to believe.

Haunting Picture

Much of Dignity‘s power flows from the book’s format—it’s not an academic work but a travelogue, weaving itinerant thoughts with personal stories from all over the United States It’s also a coffee-table book of sorts. Arnade is an accomplished photographer, and the faces and places he encounters feature prominently throughout, giving the words flesh and feeling. The pictures-and-interviews motif invites comparisons to the Depression-era photography of Walker Evans and Dorothea Lange. He is justly in their company in terms of his photographic eye, but Arnade’s artistic aims are more subdued. He paints people not as victims in need of assistance or pawns in a political game, but as they are—human beings, broken and beautiful, navigating the life they’ve got with the tools they have.

Dignity is also somewhat of a memoir, with Arnade taking part in the story he presents. His perspective as an “insider”—a former Wall Street banker who has achieved the “American dream”—sets the stage for his journey into a different side of American life. But his voice isn’t what you take with you. It’s the words of Takeesha, Imani, Luther, Jeanette, Beauty, Fowisa, Jo-Jo (all street names or pseudonyms to protect their identities), and the others you meet. It’s the drugs, chemicals of every kind that can be swallowed, snorted, smoked, or shot up. It’s the emptiness of homes, factories, cities, and towns that once held a fuller life. It’s the inexplicable persistence of community in McDonald’s, churches, bars, abandoned buildings, and parks. It’s the clear-eyed pictures of racial injustice that still pervade America—and the ways its evil seeps into and drives other class and culture issues.

Along the way, Arnade makes observations about globalization, crony capitalism, automation, family fragmentation, drug policy, and other macro-level trends that have contributed to the plight of the people he meets, but he shies away from prescriptive action steps. This gives the book a strikingly agenda-less quality. Some may find this (and the attendant lack of concrete “solutions” to “problems”) frustrating, but I think it’s a posture critical to his observations being taken seriously.

Competing Value Systems

Throughout Dignity, Arnade presents the key divide in American society as that between the “front row” (educated, workaholic, powerful, global citizens, upwardly mobile, rootless) and the “back row” (un- or under-employed, struggling, powerless, bound to place, loyal). Neither term is intended derisively—front-row and back-row America both have values and vices, even as their cultural currencies and drugs of choice differ widely. Both can provide meaning and community, but each can invite despair and breed toxicity toward the other.

Arnade makes his most helpful contributions in the question of values. The front row, he says, lives by “credentialed” value. You’re welcomed into that community based on your gifts and abilities, your degrees, your accomplishments, and your contributions to others’ well-being and success. This world is competitive and rewarding, but also insecure—you can earn your way in, but you can also fall out.

Dignity: Seeking Respect in Back Row America

Chris Arnade

After abandoning his Wall Street career, Chris Arnade decided to document poverty and addiction in the Bronx. He began interviewing, photographing, and becoming close friends with homeless addicts, and spent hours in drug dens and McDonald’s. Then he started driving across America to see how the rest of the country compared. He found the same types of stories everywhere, across lines of race, ethnicity, religion, and geography. This book is his attempt to help the rest of us truly see, hear, and respect millions of people who’ve been left behind.

In the back row, value is “non-credentialed.” Your identity and worth come from things you are born with (family, ethnicity, work ethic, local roots) or from belonging to groups accessible to almost anyone willing to join (a church, a drug community, a gang, becoming a parent).

Arnade doesn’t claim to be a Christian, but his book implicitly calls us to recover the imago Dei as the final arbiter of one another’s value.

At present, the high places of cultural influence and power are truly open only to the front row. The non-credentialed bona fides of the back row are less likely than ever before to earn you a seat at the table or a steady job. Arnade’s forays into the back row—whether in Bakersfield, California; Johnson City, Tennessee; Selma, Alabama; Portsmouth, Ohio; or even neighborhoods of front-row cities like New York—demonstrate how the solutions of the front row (“get an education,” “move away,” “get clean,” “learn new skills,” and so on) are much higher mountains to climb from this different perspective. What seems like common sense to one group feels to another like a command to turn your back on everything you’ve ever known.

Arnade persistently tells readers in the front row that the meritocracy at the helm of American society today is a much more closed system than they’d like to believe. He’s not pushing readers to advocate for better governmental or nonprofit programs for poverty alleviation, per se, but to learn to see all of our neighbors as brothers and sisters.

Where Is the Church?

Arnade doesn’t claim to be a Christian, but his book implicitly calls us to recover the imago Dei as the final arbiter of one another’s value. This lack of professed faith also makes his assessment of the earnest belief and real value of congregational life in the churches of the “back row” that much more remarkable. Arnade writes:

My biases were limiting a deeper understanding: that perhaps religion was right, or at least as right as anything could be. . . . The tragedy of the streets means few can delude themselves into thinking they have it under control. You cannot ignore death there, and you cannot ignore human fallibility. It is easier to see that everyone is a sinner, everyone is fallible, and everyone is mortal. It is easier to see that there are things just too deep, too important, or too great for us to know. (118–19)

The churches Arnade visited don’t always check all the boxes front-row Christians look for—well-articulated theology, expected behaviors, traditional political positions. But they reflect the person of Jesus Christ in loving their neighbors and being faithfully present with them. Too often, front-row Christianity (whether conservative or liberal in theology, whether high-church or low-church in polity) has trouble doing this—we’re not quite sure what we’d do if someone from the cultural back row walked in and wanted to join. The rebuke of favoritism in James 2 hits close to home. A certain way of doing church, we can get our minds around; Jesus, the wandering rabbi and friend of sinners, gives us heartburn.

But our doctrine must be embodied in our practice. Paul—Hebrew of Hebrews, Pharisee, Roman citizen—had as firm a seat in the front row of the first-century world as anyone else. His ticket was punched for success. Yet his encounter with the risen Lord sent him to the back row, where the gospel of Jesus found strong support among slaves, women, minority groups, and others for whom it was unalloyed good news. Perhaps this is why his letters to young churches in wealthy front-row cities—like Rome, Thessalonica, and Corinth—take special concern to challenge Christians to keep a cross-shaped perspective on the social realities of the family of God.

Paul gives instructions to “share with the Lord’s people who are in need,” and to “practice hospitality” (Rom. 12:13). He admonishes believers to “not be proud, but be willing to associate with people of low position” (Rom. 12:16) and to “encourage the disheartened, help the weak, be patient with everyone” (1 Thess. 5:14). He is quick to remind believers that “God chose the foolish things of the world to shame the wise; God chose the weak things of the world to shame the strong. God chose the lowly things of this world and the despised things—and the things that are not—to nullify the things that are, so that no one may boast before him” (1 Cor. 1:27–29). These characteristics should apply to the church as a whole, not simply guidelines for ministry outside the church for those who feel specially called to that.

Flipping the Script

“Associating with people of low position” in our culture is increasingly hard for people in the front row to do. This is something we should be particularly aware of in the broader Reformed tradition that places a huge emphasis on theology, study, and expositional preaching. The increasing educational and economic segregation of American life is mirrored in the church, and some unsettling observations emerge when this trend interacts with the increasing professionalization of pastoral work. The theological language used in wealthier and more educated congregations (technical terms, church history, Greek or Hebrew being used and translated, and so on—good things in themselves) isn’t as comprehensible as we’d like to think to many Americans who call themselves Christians. The expected level of education for pastors in most evangelical denominations leads those with seminary degrees (and the debt burdens that can come with them) to seek ministry roles in wealthier areas.

This selection accelerates the divide, depriving trained pastors of the opportunity for long-term learning from Christians outside their social bubble and depriving lower-income churches the chance to benefit from the good work of seminaries. The result is accidental elitism within the body of Christ, where childlike faith isn’t quite enough to burnish our identity in Christ, and where we start believing that “loving the Lord your God with all your heart, soul, mind, and strength” means having a graduate-level understanding of Scripture and theology. None of us planned for this to happen, but we’ve wound up here in part by not considering the larger cultural issues at work—precisely the things Arnade’s book beautifully exposes.

Doing Mercy with Justice

A Christian approach to bridging the divide between front and back row must wrestle with several layers of brokenness. For many Christians in front-row culture, their only interactions with those from back-row culture are in the context of mercy ministry. But mercy that only looks at material differences can do more to widen this rift than to bridge it. Poverty in the back row often has a strong material dimension (lack of wealth, housing, education, or access to social capital, employment healthcare, and so on), but people in the front row can be poor in other ways (lack of humility, meaningful relationships, generosity, and so on). Separating “the poor” from the mainstream in our thoughts and actions strips them of their dignity as divine image-bearers. If our mercy ministry isn’t married to faithful, incarnational presence, people become projects—and, given the divergent sets of values mentioned above, not very successful projects at that.

The gospel of Christ speaks of a relentlessly physical reality—an incarnate Savior who bled, died, and rose just as surely as he preached, healed, and forgave. A Christianity that asks only spiritual actions of us and promises only spiritual blessings to us might sound all right in a place where all our other needs are met, but it doesn’t always resonate the same way in a broken and hurting community. Jesus and the apostles (who were themselves largely from the cultural back row—Galileans, laborers, Roman sympathizers, political extremists) were consistently among and with the poor and broken, modeling for us a whole-body, whole-life discipleship that shakes our sense of personal worth and dislodges our stubborn pursuit of self and comfort.

Mercy ministry can’t be reduced to a set of best practices. It requires a revolution in thinking that starts to see God’s image reflected in back-row values as much as front-row ones.

Mercy ministry can’t be reduced to a set of best practices. It requires a revolution in thinking that starts to see God’s image reflected in back-row values as much as front-row ones. The stories that fill me with hope for the church all center on repenting of mutual brokenness and entering into place and presence with a wholehearted embrace of human dignity. For every church content to serve the spiritual needs of people in the front row, for whom daily life seems to work well, there is a courageous church plant in a crumbling neighborhood, relentless in relationship while applying the gospel to painful earthly realities. For every church that wants to “fix” the poor, there is a church that wants to embrace them and walk with them through their struggles. For every church that doesn’t want to “get political,” there is a congregation willing to enter into another’s suffering, acknowledging faulty social systems that have conspired to break and shame their neighbors.

But these are deliberate choices. Who is going to pay their pastor to sit at McDonald’s all day (as Arnade did) making conversation with addicts bumming WiFi and the homeless seeking warmth? Which churches will have their deacons do house calls at the extended-stay motels or tent cities under the interstate? Where are the denominations spending mission dollars to plant churches in post-industrial small towns? Who will sit in the “back row” for the sake of the gospel?

Building a Different Future

Dignity is long on observation and short on solutions—and that may be enough for starters. Christians (especially deacons and others engaged in mercy ministry) could do worse than to pick up a copy and let it open their heart to those they may otherwise be tempted to forget. I found it to be an effective “audit” of my own loves, forcing me to reckon with ways I often handicap my reading of Scripture to conform to my own sinful patterns and cultural preferences.

And lest we lose heart, there are plenty of Christians digesting the realities Arnade points out and tying these threads together in ways that can repair the breach. This is exactly what we are about at the Chalmers Center, and many, many churches and other ministries share these goals. There are wonderful ongoing conversations for transforming churches and nonprofits in ways that resist continued separation of the front row from the back.

The whole Christian story, in fact, is headed for a great reversal of just this sort:

And I heard a loud voice from the throne saying, “Look! God’s dwelling place is now among the people, and he will dwell with them. They will be his people, and God himself will be with them and be their God. He will wipe every tear from their eyes. There will be no more death or mourning or crying or pain, for the old order of things has passed away.” He who was seated on the throne said, “I am making everything new!” Then he said, “Write this down, for these words are trustworthy and true.” (Rev. 21:3–5)

All things are being made new precisely because the Son of God was willing to leave the “front row” of glory to walk among the “back row” of a fallen and fractured world: “For you know the grace of our Lord Jesus Christ, that though he was rich, yet for your sake he became poor, so that you through his poverty might become rich” (2 Cor. 8:9).

The deep brokenness Arnade invites us to see becomes an opportunity for Christlikeness. The divergent problems afflicting the front and back rows is a renewed call to, in the words of poet W. H. Auden, “Love your crooked neighbor / with your crooked heart.”