Robert Covolo has written a fascinating and original work that brings a variety of perspectives to the idea of fashion—understood as clothing and accessories, that which is worn. Scripture, tradition, and the arts all play a role in the discussion. Fashion Theology is a prime example of cultural exegesis done very well.

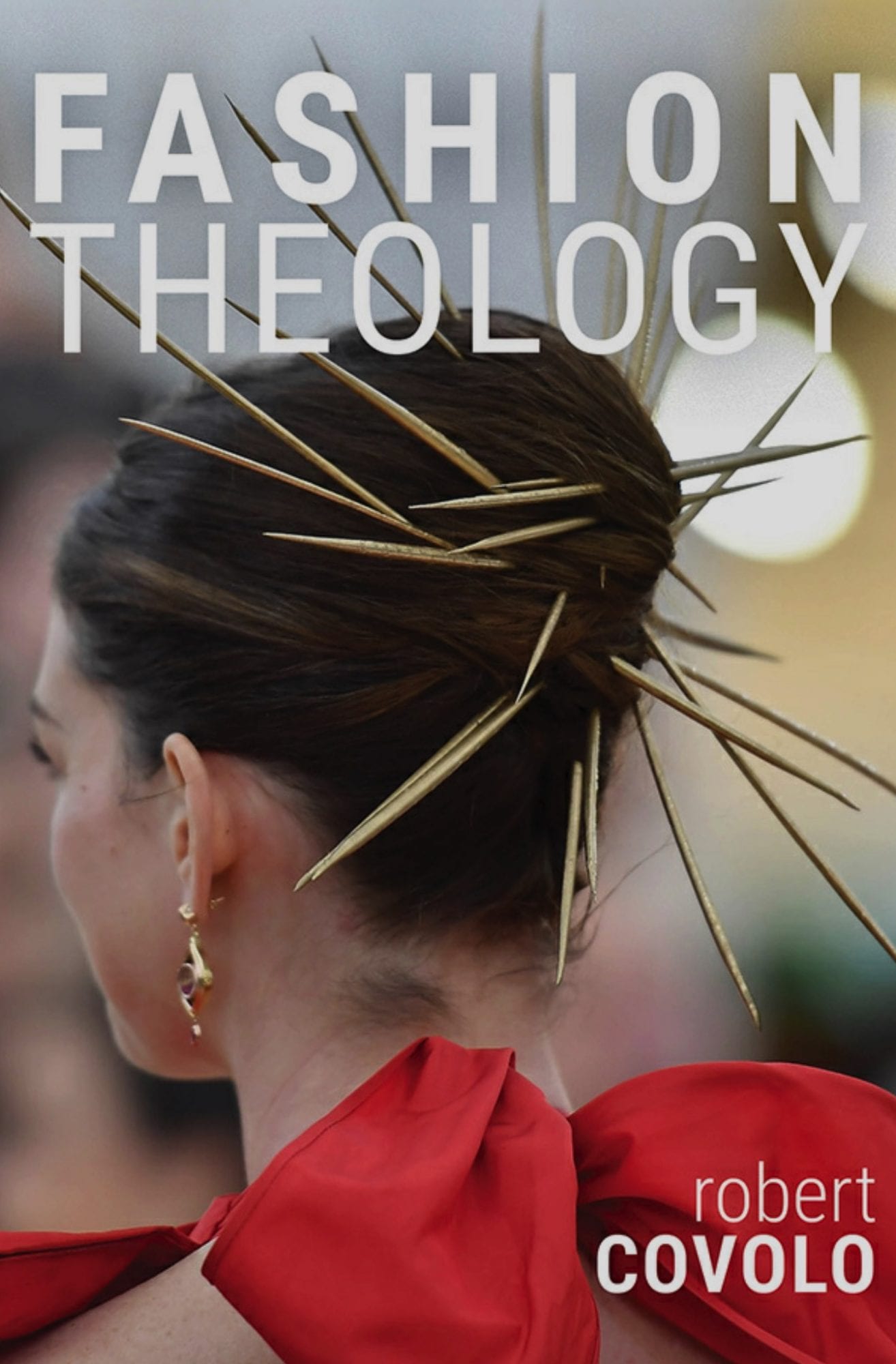

He treats fashion as tradition, reform, public discourse, art, and everyday drama. The book shows artistry in the choice of photo illustrations and apt quotations to lead sections. The depth of research informing the work is astonishing.

Aquinas as ‘High Watermark’

He begins with Clement of Alexandria (ca. 150–ca. 215) and ends with Aquinas (1225–1274), whom he regards as a “high watermark” in a Christian sense of dress. He rightly points out Aquinas’s ability to synthesize earlier patristic discussions, especially Augustine’s and Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics.

Fashion Theology

Robert Covolo

Robert Covolo retraces the way theologians have taken up fashion across history, unveiling how Christian thinkers have been fascinated with fashion well before the academy’s current focus, and bringing these insights into the conversation with fashion: the logic by which fashion operates, how fashion shapes our world, and the way fashion imperceptibly molds our personal lives.

Within fashion’s realms reside some of life’s greatest challenges: the foundations of political power, the basis for social order, the nature of aesthetics, how we inhabit time, and the means by which we tell stories about our lives—challenges, it turns out, that theologians also explore.

Fashion favors the bold; theology demands humility. Holding the two together, Fashion Theology uses an interdisciplinary path informed by a thoughtful engagement with the Christian witness. For those traversing this spectacle of unexpected crossroads and hotly contested terrain, the promise of fashion theology awaits with its myriad unexplored vistas.

He shows that relating one’s theology to dress has been of theological and pastoral interest from the earliest days of the church. His treatment of fashion and tradition reveals a weakness that repeats in subsequent chapters: lengthy endnotes containing argument and further evidence for his claims. Indeed, there are 67 pages of endnotes—more than a third of the text, which makes following his argument challenging.

Covolo turns his attention next to the early modern period, beginning with Calvin (1509–64). Fashion as reform is his theme. He dismisses any idea of Calvin as an “antifashion poster child.” True, Calvin supported sumptuary legislation in Geneva that regulated expenses concerning attire. But his commitment to Christian liberty “caused him to disdain the practice of ecclesial magistrates spending undue attention on items of adornment to be censured.”

He dismisses any idea of Calvin as an ‘antifashion poster child.’

In fact, the reformer “celebrated beautiful clothing as a God-given gift.” He considers Abraham Kuyper (1837–1920) in contrast with Calvin, because Kuyper praised “magnificent attire.” Kuyper could see that fashion was becoming a secular force in his day and hence advocated returning to a more sumptuous dress.

Covolo sees Kuyper standing as “a watershed in theology’s historic engagement with fashion.” With Karl Barth (1886–1968) the discussion moves into the 20th century. He understands Barth as a thinker who saw the “dark forces” fashion can represent. One of the great strengths of this work is that past theological luminaries are drawn into the conversation: Tertullian, Augustine, Aquinas, Calvin, and more recently Kuyper and Barth.

Fashion in Democratic Society

Covolo then deals with modern public life in a democratic society. The discussion is dense but deft. Covolo rejects a binary approach that considers fashion as top-down (the upper classes as the driver) or bottom-up (the individual as the driver).

On either view, faith has no real place in public discourse. He offers a corrective: “Therefore, this study moves from the views of fashion and faith as conflicting with public discourse (top-down) or fashion displacing faith in public discourse (bottom-up) to a different approach: the view of fashion and faith as inescapably influencing public discourse” (Covolo’s emphases). Following an insight from Kuyper, albeit nuanced, he concludes that Christians have “a vested interest . . . in participating in the space of fashion as believers in a secular space.”

On fashion as art, Covolo’s wide reading (Aristotle) and debts to the neo-Reformed tradition (Kuyper) are clear. This discussion would have been enhanced by some treatment of wearable art, both the notion and the practice, which now feature in many fine art degrees.

Wearable art educates future fashion designers to think of their work as an art form. In the college where my wife taught for many years, wearable art now dominates the curriculum and the annual fashion show. Moco Museum in Amsterdam, among others, shows wearable art. His discussion of the Catholic and Protestant imaginations and their differences is particularly valuable.

‘Performing Christ’

As Covolo reflects on fashion as everyday drama, a section he calls “performing Christ” is most refreshing. Using the lens of Christology, he covers culturally engaged dress, hospitable dress, joyful dress, convivial dress, prophetic dress, and hopeful dress. Hopeful dress is predicated on the new world Christ has inaugurated, and the “close relationship between dress and the desire for glory.” The Pauline metaphor of putting on Christ informs this part of the chapter. Covolo has the outlines of a book and I’d encourage him to write it.

Covolo covers culturally engaged dress, hospitable dress, joyful dress, convivial dress, prophetic dress, and hopeful dress.

In his introduction, Covolo identifies four fundamental issues regarding fashion: “the kind of thing fashion is, where fashion comes from, how fashion shapes the world, and the logic by which fashion operates” (2). His conclusion does not return to these questions, which is an opportunity missed. Instead, his conclusion is modest: “Given the growing domain of fashion theory, theology dismisses her at its own peril” (116).

At one and a half pages, this conclusion is too brief. He states that his aim is not to explain fashion by way of theology, or vice versa. He achieves this limited aim.

My wife is a fashion designer, fashion educator, and fashion-textbook writer. In the latest revision for one of her textbooks, the publishers want a chapter on sustainability. These days, anyone writing on fashion at any length must consider the ecological question and the work practices of production.

The definitive theological discussion of the relationship between Paris and Jerusalem—and Milan, Los Angeles, and New York—awaits. I hope Covolo provides that discussion in a future work. He has shown himself more than capable of doing so.