It seems we have come to a point where American evangelicalism’s engagement with issues of race could make or break the movement. As we stand at this crossroad, one path is to avoid problems of race in our churches and society. The other road is harder. It calls us to adapt to America’s ever-increasing diversity and become agents of reconciliation among ethnicities. It summons us to offer the nation and the world a unified cosmopolitan witness to the transforming power of Christ’s grace.

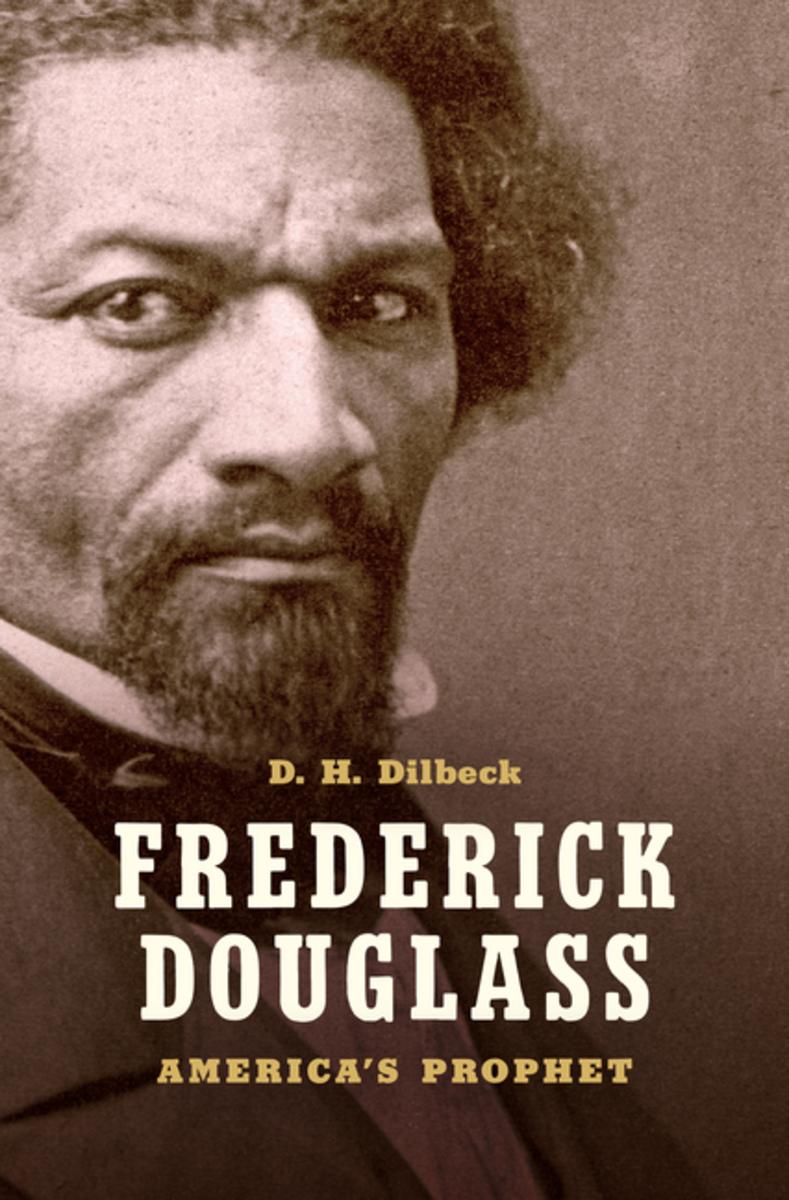

The stakes are real. At such a time as this, we need all the good resources we can muster, like D. H. Dilbeck’s recent biography, Frederick Douglass: America’s Prophet.

Learning from Diverse Biographies

Dilbeck’s biography is not designed to motivate and instruct Christians to grow in holiness. Though written for a general audience, his primary aim is academic and historical—namely, to challenge the prevailing secularized image of Douglass by showing the pervasive influence of religion on his life and work. In this respect, the book is successful and makes an important contribution to the fields of American history and African American studies. And on these grounds alone the book is commendable.

Nonetheless, Christians (especially white evangelical Americans) can learn a great deal from this biography. We hear about the ills of racism and the need to stand against it. But seeing bold and sacrificial resistance to this injustice in the lives of figures like Frederick Douglass (1818–1895) instills these principles more acutely in the soul.

It also exposes blind spots in our thinking and practice. Reading good biographies of Brainerd, George Whitefield, or Billy Graham will no doubt edify and encourage white evangelicals. But their faith and practice will be incomplete if they only learn from figures who enjoyed similar social advantages as themselves because they were white. Entering the life of Douglass in this book will similarly encourage the faith of white evangelicals, but it will also challenge them to better understand and love their non-white neighbor.

Prophet for Today

The timing of Dilbeck’s book is important, as it commemorates the 200th anniversary of Douglass’s birth. Even more, it arrives at a point of heightened tension in race relations in the United States, as white supremacist rallies, numerous white-on-black police shootings, the Black Lives Matter movement, debates over immigration, and Trump’s polarizing presidency have exposed deeply rooted racial division in America.

Almost two decades ago, Michael Emerson and Christian Smith showed in Divided by Faith that white evangelical Americans are far from immune to racial problems. The vast majority no doubt mean well, the authors argue, but most remain ignorant of the myriad ways they unintentionally perpetuate racial prejudice and inequality. Many think racism is only caused at the individual rather than systemic level, appeal to colorblind ideology, and assume America essentially overcame racism when slavery was abolished.

While the situation hasn’t dramatically changed, there seems to be at least a growing awareness among many white evangelicals today that confronting the problems of our racialized society and churches is a necessary application of the gospel—not a distraction from it. If white evangelicals prioritize political expedience over racial harmony, the movement will wither, and the gospel will be dishonored.

Frederick Douglass: America’s Prophet

D. H. Dilbeck

From his enslavement to freedom, Frederick Douglass was one of America’s most extraordinary champions of liberty and equality.

Throughout his long life, Douglass was also a man of profound religious conviction. In this concise and original biography, D. H. Dilbeck offers a provocative interpretation of Douglass’s life through the lens of his faith. In an era when the role of religion in public life is as contentious as ever, Dilbeck provides essential new perspective on Douglass’s place in American history.

To advance the kind of reformation we need, it’s essential for white evangelicals to listen to and understand non-white perspectives (as Walter Strickland so helpfully discussed in his piece on retrieving black theological voices). Good biographies (like this one on Douglass) are also an important, since they enable white readers to vicariously experience the world from a non-white perspective.

TGC recently released a few pieces on Douglass’s story (here and here), so I won’t reiterate it. Instead, I want to briefly highlight two aspects of Douglass’s life that might help white readers better empathize with the experiences and values of their black neighbors.

Different Perspective on America

First, Douglass’s life can help explain why many blacks view America and American Christianity differently than most white Americans do. Douglass had a complex relationship with America. As Dilbeck writes, “He possessed both deep affection for and deep alienation from America and American Christianity” (163). He loved his nation, but unlike many of his white contemporaries, he didn’t view America as a paragon of freedom and equal opportunity.

On July 5, 1852, the Rochester Ladies Anti-Slavery Society asked Douglass to deliver an address celebrating America’s Independence. He titled it “What to a Slave Is the Fourth of July?” and explained that while most whites in America proudly celebrate their freedom on this day, many blacks associate it with hypocrisy and shame. The principles of freedom and equality that the founders heralded in the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution did not apply to blacks.

This sentiment never really went away; it just transformed under new conditions. Even after the abolition of slavery and the civil rights movement, many blacks still question the idea that America is a shining example of virtue and equality. They still dream for a better America. On July 4, 2016, hip-hop artist Lecrae tweeted a picture of slaves working in the fields with the caption: “My family on July 4th 1776.” He was making the exact same point as Douglass: July 4 may represent freedom for most white Americans, but not for millions of blacks who identify with the struggles of their oppressed ancestors and continue to experience discrimination and marginalization in this country.

Many charged Lecrae with becoming too political and losing focus on the gospel. As he announced in the song “Facts” on his newest album, such responses led him to dissociate from white evangelicalism. If white believers can’t learn to respect and empathize with the experiences and views of their non-white neighbors, more will follow suit. And white Christians can start by learning from individuals like Douglass.

Different Perspective on Church History

Second, Douglass’s life provides white evangelicals with new perspectives and lessons from church history. Viewing the world through Douglass’s eyes can also help whites re-evaluate their unquestioned narratives of the Christian tradition. For example, the way I learned church history (primarily from the perspective of white males) led me to view the Scottish pastor Thomas Chalmers (1780–1847) as a hero for boldly protesting heterodoxy in the Church of Scotland and forming the Free Church of Scotland. Reading Douglass’s biography, however, helped me see it from a different point of view.

Douglass traveled to Great Britain to raise money and support for the abolitionist cause, and he pressed Chalmers to dissociate from Presbyterian slaveholders in America. For Douglass, their communion harmed blacks, since it lent the slaveholders credibility and suggested their actions were compatible with being good Christians. Although Chalmers himself believed slavery is wrong, he and the other leaders of the Free Church of Scotland refused to dissociate from the Presbyterian slaveholders, since they needed their financial support.

While I can still appreciate Chalmers’s bold witness for orthodoxy, my view of him and the foundations of the Free Church of Scotland is filtered through new lenses. This new perspective of the past changes the way I think and act in the present. Like the experience of Douglass with Chalmers, many blacks today hear white Christians say they love and support them, but often their decisions and actions speak otherwise. Do I prioritize political affiliations or social agendas that benefit me as a white American male, and yet harm my non-white neighbor? In the context of the church and Christian institutions, do I invite and value non-white voices that may challenge some ideas and practices I’m accustomed to as a white middle-class American?

The biography isn’t perfect. The writing gets repetitive at points, and Dilbeck seems overly invested in vindicating Douglass against any suggestion of character flaws. Even so, Christian readers will profit from it greatly. Dilbeck makes a compelling case that Douglass was the prophet America needed, and his voice continues to summon us to extend love and dignity across racial lines today. Who will listen?