In Luke’s Gospel, when Jesus enters Jerusalem triumphantly as Israel’s rightful king, his disciples praise God for the miracles they’ve seen. They rejoice and shout, “Blessed is the King who comes in the name of the Lord! Peace in heaven and glory in the highest!” In the midst of this scene, the Pharisees call on Jesus to rebuke his disciples for uttering such words. Jesus’s response is both poetic and fitting: “I tell you, if these were silent, the very stones would cry out” (Luke 19:40).

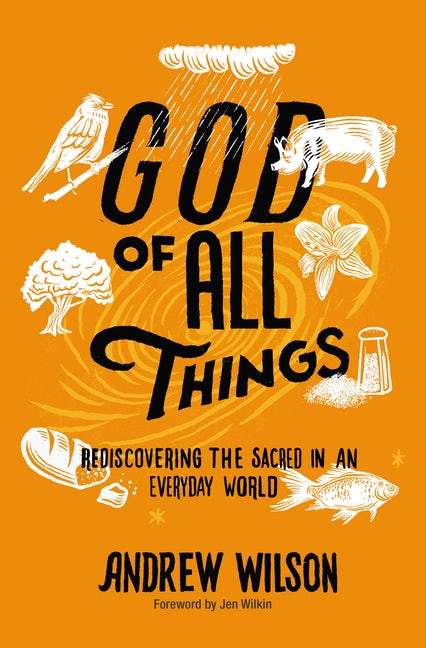

This idea, that our universe of things points to God and proclaims his glory, is the foundational thesis for Andrew Wilson’s book God of All Things: Rediscovering the Sacred in an Everyday World. Wilson, a teaching pastor at King’s Church London, poses the question why God created things—after all, he could have created only a spiritual world without physical substance.

Wilson’s answer is that the universe of things does not exist for itself, but to draw humanity back to God: “The things of God reveal the God of things” (3). Far from being an anthropomorphic world, where things reflect human attributes, Wilson argues delightfully that the world is actually theomorphic: “things take the form they do because they are created to reveal God” (4).

We describe God as “the Rock” not just because rocks exist and they provide a good picture of safety and stability. Rocks exist because God is the Rock: the Rock of our salvation, the Rock who provides water in the desert, the Rock whose work is perfect and all his ways are just. . . . Ever since the beginning, the surface of this planet has been covered in rocks, and every one of them has been preaching a message of the faithfulness, security, and steadfastness of God. (4)

God of All Things: Rediscovering the Sacred in an Everyday World

Andrew Wilson

God of All Things: Rediscovering the Sacred in an Everyday World

Andrew Wilson

Abstract theology is overrated. In the contemporary West, we’re desperately in need of rediscovering God through ordinary, physical things we see in the world around us. Jesus did it all the time. He mentioned a lily, sparrow, sheep, coin, fish, harvest, banquet, lamp, stone, seed, and vineyard to teach about the kingdom of God. In the Old Testament, too, God repeatedly describes himself and his saving work in relation to physical things such as a rock, horn, eagle, shelter, cedar, lion, shield, wave, ox, and so on. Ask the beasts, and they will teach you; the birds of the heavens, and they will tell you; or the bushes of the earth, and they will teach you (Job 12:7-8).

In God of All Things, pastor and author Andrew Wilson explores glimpses of the sacred in created things, finding in them illustrations of the character and gospel of God. As humans, we encounter glory through stars and awe through storms. We learn about humanity through dust and about Jesus’s death on our behalf through trees and bread and wine. Ultimately, we meet God in his creation. It is a gallery full of sketches, paintings, and portraits revealing our Maker and Savior. Wilson presents a variety of created marvels—from figs and galaxies to viruses, pigs, and honey—that reveal the gospel in everyday life and fuel worship and joy in God.

For Wilson, things are not just composites of matter and molecules. They are signposts pointing to a creator God, so that we can marvel and wonder at the majesty of the One who sustains the universe and everything in it. If we look closely, every created thing can proclaim God’s character, whether it be his majesty, his goodness, his creativity, or even his sense of humor.

Wonderful and Whimsical

Of the billions of things in the universe that could testify to God’s inherent goodness, pigs would not be a first thought. They were rejected by the Jewish dietary laws of the Old Testament as unclean. Wilson notes that there is a certain theological parallel between unclean animals and the Gentiles, who were also regarded as unclean, and therefore separated from God’s people and from God himself. But then Wilson describes Peter’s vision in Acts 10: a sheet descends from heaven filled with unclean animals (which must have included pigs), and a voice tells Peter to eat, since “what God has made clean, do not call common” (Acts 10:15).

If we look closely, every created thing can proclaim the character of God.

Wilson calls this the “pig paradox,” in which an unclean animal, through death, becomes, well—bacon, prosciutto, BBQ ribs, and braised Korean pork belly (the last is my addition to Wilson’s mouth-watering list). The unclean and dirty is transformed to something aromatic and delightful. Things you would not have wanted to touch become transformed by God into something fragrant and irresistible, a sign of God’s redeeming goodness—and its tastiness (Ps. 34:8).

Many of Wilson’s 15 Old Testament examples are like the “pig paradox.” Dust, stones, donkeys—they all seem like common things, some of them so whimsical that their spiritual significance is obscured. If, however, we see these formerly common things through the right lens, they become signposts directing us to worship God. Dust reminds us that dry bones in a valley of death will be filled with divine breath and raised to life. Stones point us to the passage in Psalm 118 where the stone rejected by the builders becomes the chief cornerstone. Donkeys (possibly earth’s most stubborn creature) remind us emphatically that, yes, God has a sense of humor, and, no, we cannot control everything.

Judgment and Redemption

Many of Wilson’s 15 New Testament examples will be familiar: salt, water, bread, trees, cities, light. Despite their familiarity, Wilson breathes new life into these examples, unearthing their cultural and societal significance that Jesus’s listeners would have recognized.

When Jesus tells his followers they are “the salt of the earth” (Matt. 5:13), he refers not simply to salt as a seasoning, but as an element used to judge and destroy. For example, in the Gospel of Mark, Jesus pronounces judgment by proclaiming that “everyone will be salted with fire” (Mark 9:49). So by telling his followers they are the salt of the earth, Jesus proclaims that he is scattering his disciples onto the earth as a sign of judgment, as a way of rooting out wickedness, lust, greed, and murder from our world. “The very existence of the church, preaching and living out the gospel, proclaims judgment against the enemies of God,” Wilson writes (109).

Looking at Our World

Wilson has written a book for those of us who rejoice at seeing visible and tangible reminders of God’s sovereignty and goodness in our everyday world. But there is an unwritten assumption here. We will only see God in these visible, material things if we are already looking at our world through the right lens. We should therefore be cautious about relying on the natural world to persuade our postmodern culture that the God of the Old and New Testaments is real. Only the gospel of the resurrected Christ can do this, and only hearts changed by the gospel will see the everyday world for what it really is.

We will only see God in these visible, material things if we are already looking at our world through the right lens.

As our own minds are transformed by the gospel, everyday objects become delightful and wonderful confirmations that God is indeed faithful, his love endures forever, and we will never be alone, in this life or the next.

And on that last day, when believers from every nation and tongue gather together to lift our praises to the King, the stones will cry out and all of us, both creation and the created, will sing together at last.