Imagine a college freshman reading in the library. All her life she has believed that the universe is 6,000 to 10,000 years old, and that the days of Genesis 1 are 24-hour periods of time. Godly Christians with PhDs said so, and she accepted their claims. Opposing views were not presented sympathetically.

Now she is struggling deeply with her geology textbook. She is surprised at the strength and versatility of the evidence for an older earth. Her teachers don’t seem to be intentionally promoting a “secular” agenda, as she expected. The idea that so much in her textbook is wrong feels too conspiratorial to be plausible.

What will happen to her faith?

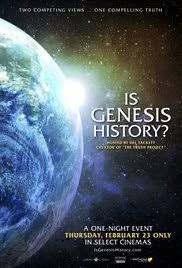

This is a fictional scenario, but not an uncommon one. And it touches on my concern with the movie Is Genesis History?, released in limited theaters earlier this year. The film is directed, written, and produced by Thomas Purifoy, narrated by Del Tackett (creator of The Truth Project), and features interviews with 13 scientists from varying disciplines.

Is Genesis History?

I appreciate the film’s intent to uphold a biblical doctrine of creation. I embrace those involved in the film as my brothers and sisters in Christ, and as sincere in their views and efforts. All Christians can appreciate the film’s excellent graphics and many beautiful shots of nature, drawing attention to the intricacy and intentionality of our world as the handiwork of God, not the result of blind processes.

Although I have a different perspective on creation, I am grateful that Christians may partner in the gospel despite differences we may have on the question of the age of the universe (as we seek to do, for instance, within The Gospel Coalition). In this review, I will focus less on my disagreements with young-earth creationism as such, which I’ve written about elsewhere.

Instead, I want to address how the film makes its case, which I see as the more urgent, pastoral issue at stake (the “freshman-crisis-of-faith” scenario, recounted above, is very much on my mind).

In this respect, I have three basic concerns with Is Genesis History? First, the film presents young-earth creationism as the only viable alternative to naturalism; second, it equates young-earth creationism with a “historical” reading of Genesis; and third, it provides an occasionally prejudicial and/or misleading account of the evidence in favor of young-earth creationism.

Are Young-Earth and Naturalism the Only Options?

At the climax of its introduction, the film presents a series of contrasts:

- Was the world made in a few days or over billions of years?

- Are we descended from apes or created instantly in God’s image?

- Was there a global flood, or is the flood story a “myth”?

“In other words,” Tackett summarizes, “is Genesis history?”

Ultimately, the movie presents two options: full-blown naturalistic evolution, in which all life is created by “strictly physical processes,” and the “historical Genesis paradigm” (young-earth creationism).

This way of framing the debate, however, excludes from visibility a huge portion of Christendom. Viewing the world as neither “naturalistic” nor “young” is the position of a wide array of Christians as diverse as C. S. Lewis, Billy Graham, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Charles Spurgeon, William Lane Craig, and the Pope. Indeed, many stalwart defenders of biblical inerrancy (such as B. B. Warfield or Gleason Archer) and staunch opponents of liberalism (such as J. Gresham Machen) affirm both the historicity of Genesis and also an ancient universe. Unfortunately, viewers will not be aware from watching this movie that such positions even exist.

Interestingly, philosopher of science and young-earth creationist Paul Nelson—who introduces the terms “conventional paradigm” and “historical Genesis paradigm” in the second interview, which are then sustained throughout the film—subsequently dissented from his own role in the film. In his explanation why, he argued, “We should organize the range of current opinion about origins around the deepest or most significant differences that separate positions—and that isn’t the time scale involved.”

I share Nelson’s concern, and appreciate his speaking out. The most important contrast is not simply old versus young, and when we cast the debate in that way, we present viewers with a simplified view of the options.

Any treatment of creation views in which C. S. Lewis, Billy Graham, and John Stott don’t even show up on the radar screen can’t be telling us the whole story.

What Is a ‘Historical’ Reading of Genesis?

Like the creators of Is Genesis History?, I believe Genesis is “historical,” and I affirm the complete truthfulness of its account of creation. But throughout the Bible, there are different kinds of historical narration, and many “historical” passages involve stylized, broad stroke, idiomatic, and/or symbol-laden language. For instance, the song of Deborah and Barak in Judges 5 describes historical events, yet it obviously does so differently from, say, Judges 4. To read the Bible well, we must appreciate the literary character of its historical and theological narration.

Is Genesis History? does not seem interested in such hermeneutical issues. The biggest problem in this regard is the failure to distinguish Genesis 1 from the rest of the book. Virtually all interpreters recognize significant differences of tone, style, and language between Genesis 1:1–2:3 and the subsequent material. The film does not even mention this point; in fact, in the third interview Tackett denies any distinction between the creation story and the subsequent chapters of Genesis.

Potential literary differences between Genesis 1–11 and Genesis 12–50 are also unexplored. J. I. Packer distinguished the “poetic-prose mode of narration in Genesis 1–11, with its pictorial, imaginative, quasi-liturgical phraseology, its paucity of mere information, and its drumbeat formulae” from the “ordinary narrative prose mode” of Genesis 12–50. At the same time, Packer rejected the labels “legend, saga, epic, myth, or tale” to describe Genesis 1–11, affirming them as “space-time history, although told in [Moses’s] chosen incantatory-poetic way.”

If the film had argued that the young-earth interpretation is the most faithful “historical” reading of Genesis, over and against a view like Packer’s, viewers would at least be introduced to some of the nuances involved in this issue. Unfortunately, Is Genesis History? will likely give the impression that the choice is simply between 24-hour days or “myth/poetry.”

Misleading Appeals to Data

The film’s overall opposition to the naturalistic worldview that tugs at our culture should be welcomed, and many of the specific appeals to design and order in our world are helpful to this end. The film could have made a stronger case against naturalism if it had engaged a wider array of scientists—all 13 interviewees in Is Genesis History? are young-earth creationists. And regrettably, some of their arguments for a young earth appeal to selective, misleading, and/or exaggerated data.

In the first interview, for example, geologist Steven Austin remarks, “The story that we all learned in grammar school—(the) Colorado River over tens of millions of years cut the Grand Canyon—most geologists have jettisoned that idea.” He asserts that this view is impossible, and argues that the Grand Canyon was formed through “catastrophic erosion by drainage of lakes.”

There is some debate among scientists about how many millions of years the formation of the Grand Canyon took (70 million years or 5 million to 6 million years?), but outside the young-earth camp few if any scientists would question that the Colorado River did the carving, and that it took millions of years. It’s misleading to give viewers the impression that what’s being “jettisoned” by “most geologists” is this basic idea (Colorado River + millions of years).

Another example comes in the third interview, when Hebraist Steven Boyd is asked whether the days of Genesis 1 are literal or poetic. He responds by emphatically asserting that “the world’s greatest Hebraists all affirm that this is narrative,” distinguishing the biblical account from poetic creation stories in the Ancient Near East. In the context of the question being addressed, his answer seems to conflate “non-poetic” with “24-hour days,” and thus the appeal to “all” the world’s “greatest Hebraists” is more rhetorically impressive than representative of truth.

To be fair, some of the other scholars interviewed were more responsible in their claims. For instance, while Todd Wood did not persuade me that Neanderthals were human beings, I appreciated that he made his position clear and admitted there are unanswered questions. Similarly, I’m not sure what to make of Danny Faulkner’s appeal to rapid maturing to explain the challenge of starlight, but at least the difficulty is apparent in his discussion, and he doesn’t claim any false authority for his answer.

Inadvertent Effects

Ultimately, I worry that the methodology and mindset presupposed by Is Genesis History? may inadvertently hinder our unity and witness as the church. Zealous atheists watching this film will likely find ammunition by which to confirm their warfare model of “faith versus science.” Sincere skeptics may experience it as an obstacle to faith. Christians who lack an interest in science or creation issues may experience the “college-crisis-of-faith” scenario above. Evolutionary creationists watching will likely feel their view was not well represented (for instance, in the final interview and conclusion). And old-earth creationists will probably feel simply ignored.

For these reasons, I would not recommend this film to pastors and church leaders as a discipleship tool unless used in coordination with other resources, and I would encourage all its viewers to engage with it critically, testing its claims in relation to alternative views of creation.

Related:

- Theological Triage and the Doctrine of Creation (Sam Emadi)

- Controversy of the Ages: Why Christians Should Not Divide Over the Age of the Earth by Theodore Cabal and Peter Rasor (Weaver Book Company, 2017)