One wonders why a 19th-century theologian would attract the enormous throng of biographers who have concentrated on John Henry Newman (1801–1890). Library shelves around the globe are weighed down by the several hundred volumes dedicated to Newman’s life, many of which are written with the most fastidious attention to detail. Opinions about Newman’s legacy are as variegated today as they were a century ago, and new studies seem to come forth every year. But the book under review, John Henry Newman, stands apart from the rest.

The author is Ian Ker, senior research fellow at St Benet’s Hall, Oxford. A Catholic priest, theologian, and prolific writer, Ker is considered by many to be the foremost expert on Newman. He initially published Newman’s biography in 1988 as the first comprehensive, full-length treatment of Newman’s life and thought. Having become the standard, the revision of this volume was inevitable. Its 772 pages of carefully researched and lucidly written narrative escorts readers to Victorian England to behold the complexity and contrast of Newman’s character: everything from his infamous despondency to his passion, tenacity, and even his humor.

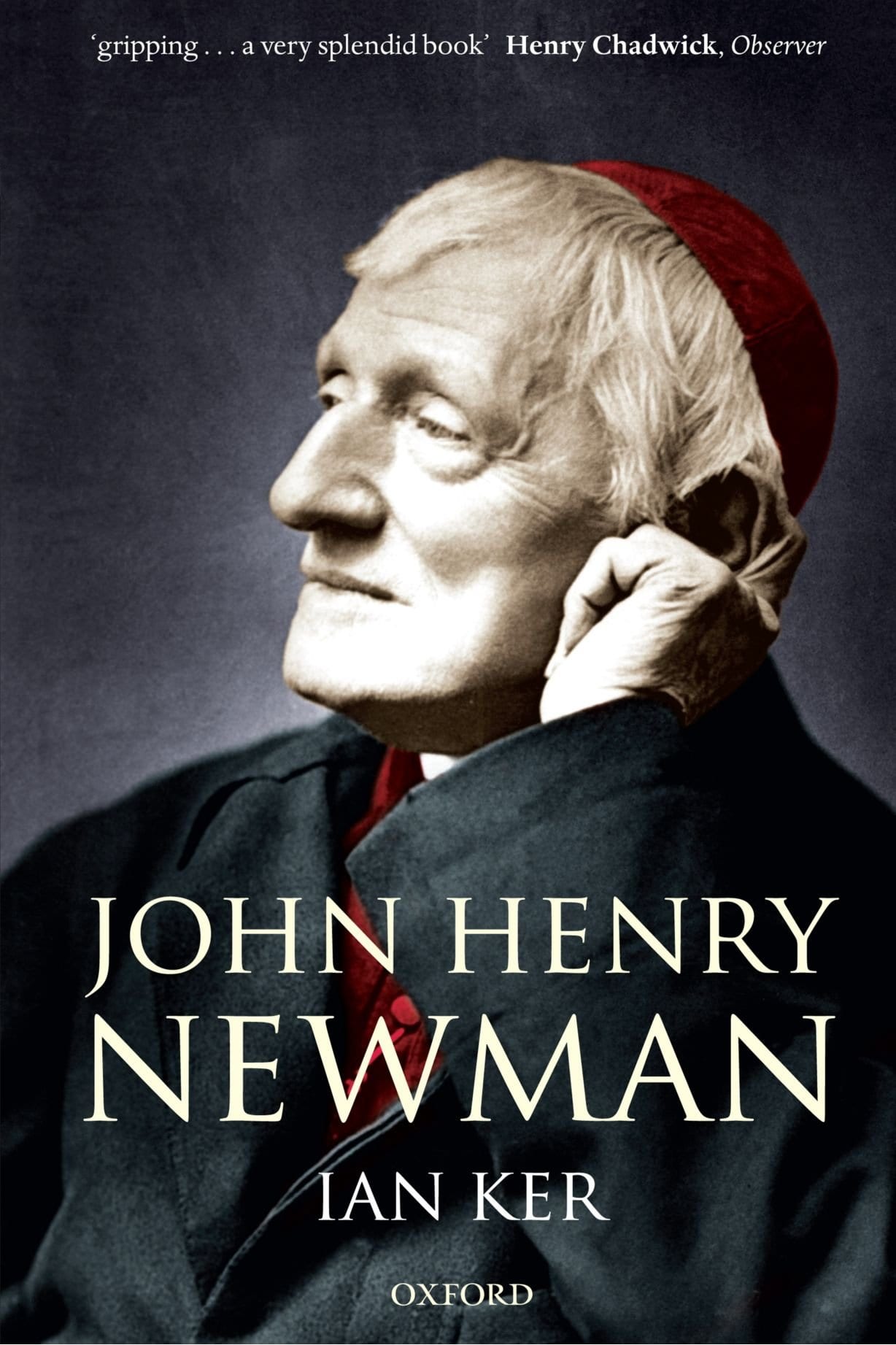

Regarded by many as the eminent and most creative English theologian of the 19th century, John Henry Newman is remembered in a variety of ways: leader of the Oxford movement, Victorian sage, writer of prose, convert from Calvinism to Catholicism, poet, educational theorist, cardinal of the Catholic Church, forerunner of Vatican II, and most recently beatified by Pope Benedict XVI.

Newman’s Apologia Pro Vita Sua (A Defense of One’s Life) is often compared to Augustine’s Confessions as among the most outstanding accounts of a personal conversion. His Grammar of Ascent, written against the backdrop of anti-Christian Empiricism, remains one of the finest apologetic works of all time. His magnum opus, The Idea of a University, envisages education that serves society with a thoroughgoing commitment to the disciplines of philosophy and theology. With these and other works, Newman continues to inspire generations to pursue serious-minded reflection in the Catholic tradition.

John Henry Newman

Ian Ker

This full-length life of John Henry Newman is the first comprehensive biography of both the man and the thinker and writer. It draws extensively on material from Newman’s letters and papers. Newman’s character is revealed in its complexity and contrasts: the legendary sadness and sensitivity are placed in their proper perspective by being set against his no less striking qualities of exuberance, humour, and toughness.

So why should an evangelical Protestant living in the 21st century invest the time and energy to read this tome? Let me propose a few of reasons. First, for all of our differences with Newman’s theology, he is, nevertheless, a fine example of the pastor/scholar. For instance, Newman lost his tutorship at Oriel College when he wasn’t allowed to serve his students as a pastor (40). It was his conviction that the position carried shepherding responsibilities, while the provost, Edward Hawkins, insisted that tutorships were strictly academic. When Newman objected, Hawkins deprived him of new students, leaving him no option but to resign.

In addition to insisting upon the pastoral nature of education, Newman was committed to preserving the coherency of faith and scholarship. In his words, “Religion and knowledge are not opposed to each other . . . they are indivisibly connected” (384). In other words, redemptive history, precisely because it is God’s story, is the larger context in which education needs to happen.

You will also be heartened by Newman’s arguments for the objectivity of truth and veracity of Christian orthodoxy. He was serious about doctrine, often at great personal expense. This is observed in his days as student at Trinity, Oxford, when he relied upon God’s providence amidst great crisis (14) to the years following his conversion when he seemed to have more enemies than friends. In our current day, when theology is marginalized in many sectors of the church, Newman’s example of theological conviction speaks loudly. It is in the context of personal ecclesial battles that Ker’s chronicling is the most riveting.

A study of Newman acts as a guide to modern Catholicism. There is a reason, for instance, why Vatican II (1962–1965) is sometimes called “Newman’s Council” (411). It is because Newman’s ideas, especially from his book An Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine, provided many of the hermeneutical underpinnings upon which Catholic theology has been built over previous decades. Born out of an attempt to respond to Protestants who argued against the apparent discrepancies between the Roman Church and the Bible, the concept of “development” sought to explain “the contrast which modern Catholicism is said to present with the religion of the Primitive Church” (702). Understanding this concept goes a long way for evangelical pastors trying to equip their churches to relate with redemptive intentionality toward Catholics.

Evangelicals should also read Newman to be reminded that the via media (“middle way”) is often more an illusion than a reality. In his search for an Anglican consensus, Newman wrote his Lectures on the Prophetical Office of the Church Viewed Relatively to Romanism and Popular Protestantism. This is the foundational document for his via media, along with his Lectures on the Doctrine of Justification. Given space limitations, I’ll summarize Newman’s via media with a statement from another of Ker’s reviewers who described it as “an imploding position and one more full of holes than St. Peter’s fishing net.” I agree. At the end of the day, Western Christians are either Catholic or Protestant. The fact that Newman ultimately landed in Rome seems to illustrate this truth.

For all of its strengths, one should count the cost before purchasing this volume and setting aside the weeks that it will likely take to read it. First, for all of its thoroughness, there are evangelical questions that this book doesn’t answer. For instance, there is nothing on Newman’s association with John Nelson Darby and Newman’s remarkable similarity to Darby’s dispensational method of interpreting the Old Testament (John Henry’s younger brother, Francis Newman, was a close friend of Darby and active member in the Plymouth Brethren). Evangelical readers will also want more information about Newman’s view on justification, about which he had a great deal to say (see his 400 page Lectures on Justification).

My advice is this: If you want to learn about Newman, checkout the volume with the same title by Avery Cardinal Dulles SJ. If, however, you are sufficiently motivated to read the unabridged version, there is no better volume than this one.