I picture an unbroken horse.

It’s still—at least for the moment—and staring me down with its massive, sloping head. Its eyes flicker and a shudder of muscle runs down its body. I move carefully because I know the animal is liable at any moment to explode into movement, and the last I’ll see is a flash of incredible power as it crashes away, hooves sparking off into the dark.

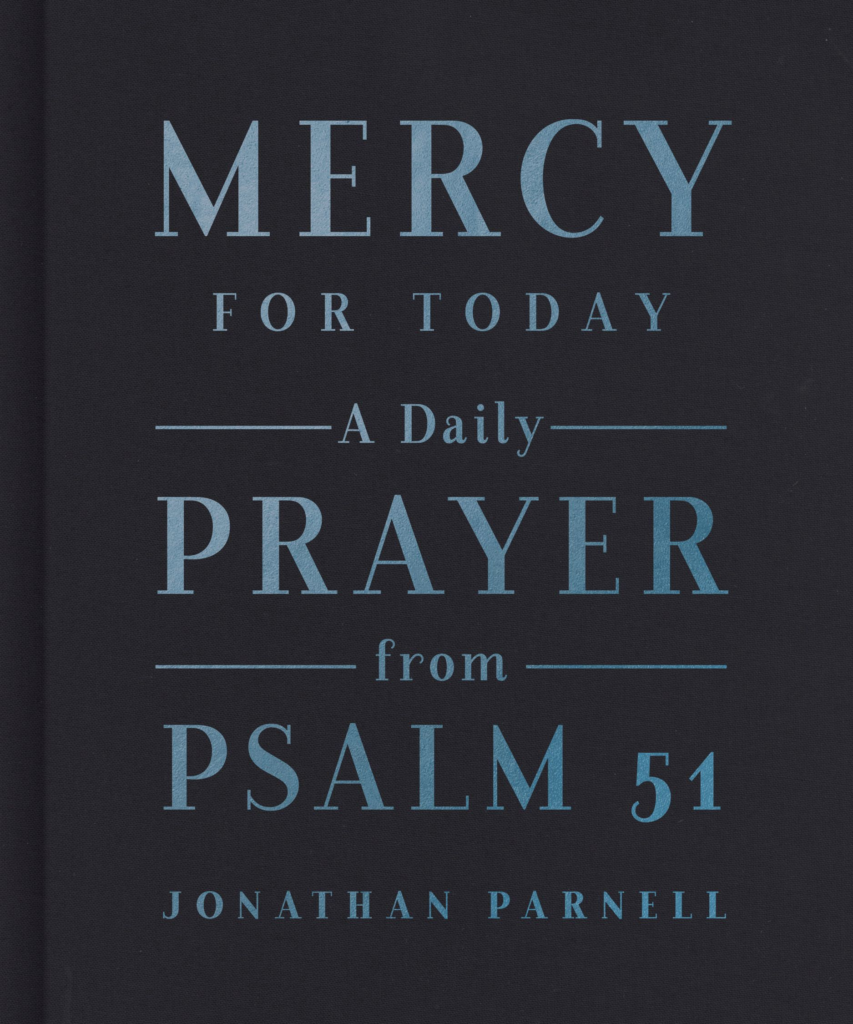

This is the image I conjure when I think about my own heart. And it’s the image that occurred to me over and over as I read Jonathan Parnell’s new book on prayer, Mercy for Today: A Daily Prayer from Psalm 51.

You may understandably ask, “What does an unbroken horse have to do with your heart, or with prayer?” I’d answer: only everything.

Mercy for Today: A Daily Prayer from Psalm 51

Jonathan Parnell

Do we just need God’s grace in dark and shameful moments? Are prayers for mercy only for those times when we really mess up? Jonathan Parnell says we need God’s mercy all the time. In fact, contrary to many church cultures, Parnell shows that asking God for mercy should be as regular as asking God for our daily bread.

Primer on Prayer

Parnell sees prayer as the bridge across the gap between the head and the heart:

Even if our emotions don’t line up, even when it seems like everything in our lives is falling apart, our mouths can still join the chorus of God’s adoration. We can say true things without feeling them. . . . In other words, we can lead our hearts with our mouths.

Parnell’s book is a tight concept: how to pray a short, daily prayer based on Psalm 51.

Of course, it’s about a lot of other things, too. It’s about our desperate need for God’s mercy, why it’s OK to ask for the emotional experience of joy, the core need for God’s presence, and plenty more. All of this grows out of his tracing the contours of David’s prayer in Psalm 51.

You should pick it up and read it for a lot of reasons. It’s pleasantly compact and accessible. It has some great nuggets on praise, confession, melding our experience with God’s truth, and a few tasteful nods to John Owen and some other great thinkers.

But Parnell is at his best when he writes about the human heart, especially when he quotes Pascal: “The heart has its reasons of which reason knows nothing.”

Profound Gap

Parnell finds a way to drop into Pascal’s theme a couple of times throughout the short book, and each time with a similar thesis: we should use prayer to lead the heart. Without prayer, we can’t trust where it goes.

We should use prayer to lead the heart. Without prayer, we can’t trust where it goes.

I always thought I’d finally grow into a person who prays as I became more pious and well-behaved. I had in mind some older and steadier version of myself, bowing his head in delighted duty. I was totally wrong.

Actually, it’s the unpredictable and panicky version of myself, the version of myself that has lived long enough with my heart to see it as the fear-filled, addiction-prone, praise-seeking, comfort-mongering, people-manipulating, idol-prone wild beast that it actually is—that’s the version of myself that has actually become a praying man.

Because I have to stare this wild horse in the face every morning. I have to whisper to it, “Stay with me,” whenever it catches the slightest whiff of fear. I have to steady it with the Psalms and romance it with the love story of Jesus’s death and resurrection before it’ll come along towards the love of my God and my neighbor.

This is the kind of broken person who finally says, “Create in me a clean heart, O God,” and, for the first time, at least wants to mean it.

Trouble with the Heart

I’m not unique in my trouble with this wild horse. (The wild horse, by the way, is not imagery Parnell uses. It’s the picture that kept springing to mind as he wrote about our “spastic emotions.”)

Cultural criticism is replete with the common grace of this wisdom. Reading Parnell, I was reminded of Woody Allen’s quip, “The heart wants what it wants,” or Carson McCullers’s ringer, “The heart is a lonely hunter.”

Rather than over-romanticizing our depravity, Parnell rightly prefers the prophet Jeremiah’s bluntness on the subject: “The heart is deceitful above all things, and desperately sick; who can understand it” (Jer. 17:9).

Only the heart trained in the prayers of Scripture is free to sing the praises of the grace that set it free.

As Parnell led me to dwell on this again, I was reminded that this theme isn’t a cultural hypothetical. It’s the reality that haunts us all.

I think of my alcoholic grandfather, who finally gave up the bottle and trusted Christ sometime in his 50s. As a child, I watched him carefully monitor his life, keeping routines and eccentric charts of cigarettes and communions—only decades later would I understand he was tip-toeing around a heart he deeply mistrusted, trying to cooperate as the Good Shepherd led his heart to stiller waters.

I think of a friend fighting depression, a neighbor who happened to lose her mother and break both her legs in the same year, a friend of my wife’s faithfully hanging on to a pregnancy with twins despite one baby having already died and the second having a low chance of survival.

The commonality between all of us isn’t that we’re wrestling with the things outside of us: alcohol, dead family members, broken femurs, depressive bouts, and insurmountable medical odds. It’s that we’re all wrestling with the wild beast inside of us, which desperately desires to run off to the wild in both the most normal and the most dire of circumstances.

The problem is within.

This is why the church must preach to its neighbors the saving grace of Jesus Christ; and this is also why the church must preach to itself the sanctifying grace of Jesus Christ that comes in the discipline of prayer.

Parnell’s book is a great reminder on this front. Over and over he helped me remember that a right response to Jesus’s mercy is to pray “ahead of our hearts.”

Practicing Prayer

For a book about the value a particular daily prayer has played for Parnell, I wish there was a page that displayed the prayer more prominently. It’s tucked in there on page 22, but, after being convinced I too wanted to pray this prayer regularly, I wished there was a title page on which the prayer was easier to find. I suppose that’s a compliment, too, because Parnell’s book certainly reinforced my desire to use formational prayers such as the one he proposes.

It reminded me that if all this business about the wild heart is true, then worship is inevitable. The inevitability of worship means the inevitability of prayer.

In this sense, we’ll always start our days praising or petitioning something. We’ll continue and end them with more of the same: groans and yearnings in the prayer or adoration of lesser idols, unless we explicitly direct these inevitable prayers to King Jesus.

Why would we let our untrustworthy hearts spontaneously lead our prayers? Why not let trustworthy Scriptures lead the heart?

This is where Parnell’s musings on the heart aren’t just profound, but practical. Why let our untrustworthy hearts spontaneously lead our prayers? Why not let trustworthy Scriptures lead the heart?

This is, of course, nothing more than the wisdom and grace of discipline. Only the jazz musician who knows his scales cold is free to improvise. Likewise, only the heart trained in the prayers of Scripture is free to sing the praises of the grace that set it free.

This Morning

This morning, like each one since I finished Parnell’s book, my prayer briefly retraced the contours of Psalm 51: mercy, praise, confession, presence, and joy. It’s a comforting rhythm.

But even more, in those same moments, I’m picturing the wild horse I’ve always pictured, but now with a bridle in its mouth.

I watch a rider gently tug the bridle, directing the horse’s head to the open field. Here’s true freedom. A safe place to run wild, where all that fearsome muscle and energy can crash around in glory, because grace pointed it in the right direction.

That’s the power of prayer for the wild heart.