Becoming a Christian is, generally speaking, bad for a novelist’s career. With some exceptions to this this rule (Marilynne Robinson, for one), a committed Christian in the world of letters faces bewildered misunderstanding from the literary community and, often, a Christian community expecting every story to follow the plotline of “Amazing Grace.” Someone compelled by both a gospel faith and a literary vision will sometimes end up forgotten by both communities. That is, I suppose, how Frederick Buechner ended up in exile here among the born again.

Despite the fact that Buechner was a groundbreaking and award-winning novelist even in his early 20s, he’s not remembered in the world of The New York Review of Books alongside, say, a John Updike or a John Cheever. And despite being drawn back to the church and ordained to ministry after listening to a George Buttrick sermon, Buechner is hardly as celebrated as one would expect among his Union Seminary mainline Protestant ecosystem. Much of that sector of American religion has moved on to forms of theology that would see Buechner as hopelessly retrograde compared to various liberation theologies and deconstruction philosophies now in fashion. Instead, when one finds a person whose life is changed and shaped by reading Frederick Buechner, more often than not, that person is an evangelical like you and me.

Writer We Need

As I’ve written elsewhere, Buechner’s work transformed my life at an early age, helping me through a spiritual crisis that might have led me, like so many others, right out of the church. Buechner, though, along with the Inklings and others, proved to be the apologist I needed, demonstrating how the longings of the human heart point to something of which only the gospel can make sense. Having read every work of Buechner’s multiple times, I find that not two weeks go by that I do not read him again.

Having read every work of Buechner’s multiple times, I find that not two weeks go by that I do not read him again.

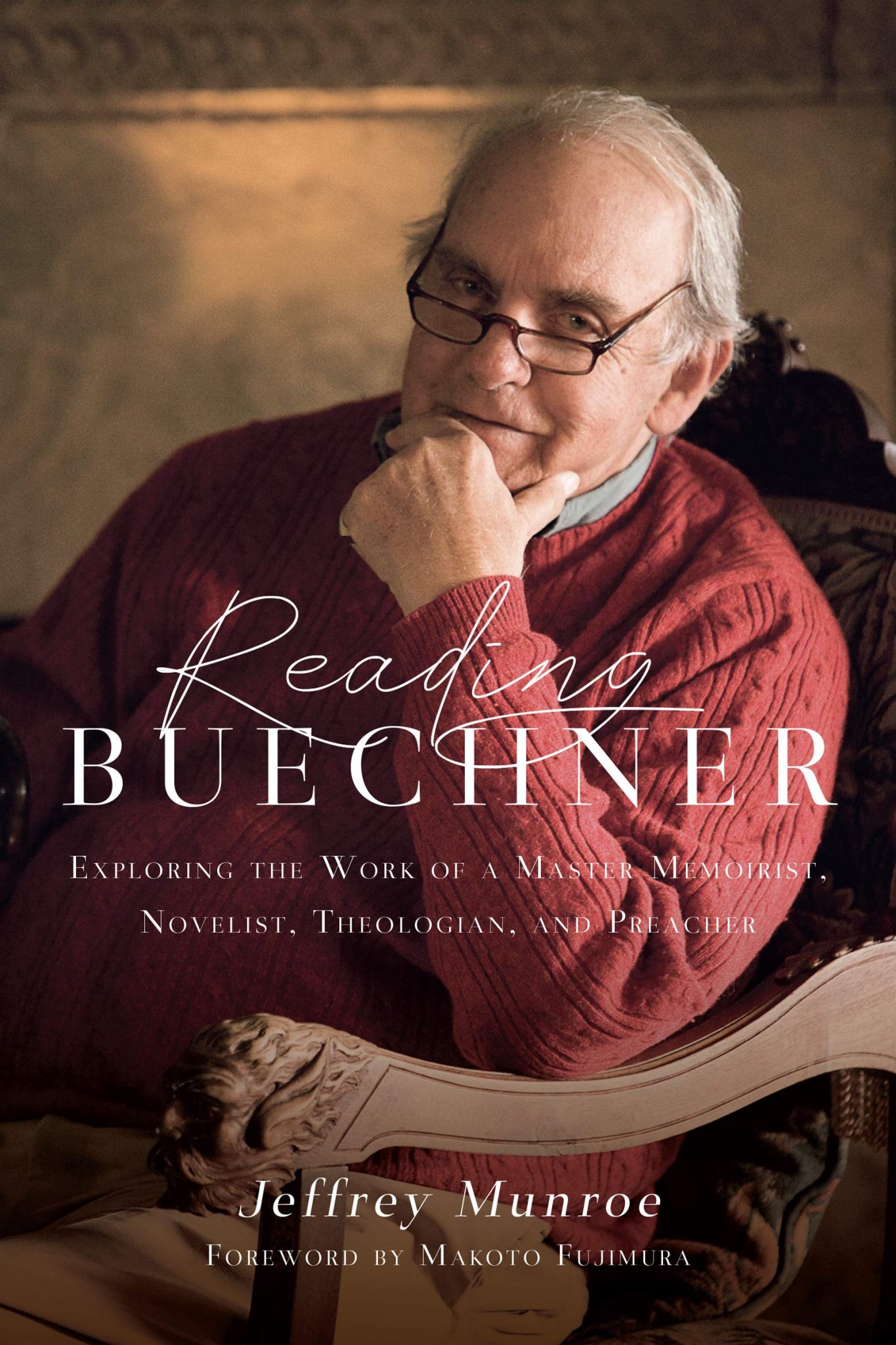

So I was glad to see, months ago, a notice of this book: Reading Buechner: Exploring the Work of a Master Memoirist, Novelist, Theologian and Preacher by Western Theological Seminary executive vice president Jeffrey Munroe. When the book was recommended to me on Amazon, I immediately texted it to friends, all fellow evangelicals, knowing they would want to pre-order it as well. And I wasn’t surprised to see that it’s published by InterVarsity Press, an evangelical house. My initial thought was, I hope it’s good, because evangelicalism needs Buechner, perhaps now more than ever before.

Reading Buechner: Exploring the Work of a Master Memoirist, Novelist, Theologian, and Preacher

Jeffrey Munroe

Reading Buechner: Exploring the Work of a Master Memoirist, Novelist, Theologian, and Preacher

Jeffrey Munroe

I needn’t have worried. The book is good—thoughtful, engaging, comprehensive, from an author who knows the Buechner corpus and is thoroughly competent to wrestle with the theological and spiritual questions Buechner raises. Monroe also analyzes Buechner’s literary prowess and situates his work in the historical context of the 20th century and in Buechner’s own tragic-comic life from his father’s suicide onward. Reading Buechner succeeds because it communicates the integrity of Buechner’s life and work, by which I mean the way that it holds together with the coherence and complexity of a human life.

What to Read First?

This book is welcome for several reasons, but one of them is because I struggle to answer a question about Buechner’s work from my fellow evangelicals. Sometimes an evangelical, knowing how influenced I’ve been by Buechner’s work, will ask, “If I want to try out Buechner, where do I start?” I don’t know how to answer that question, because Buechner’s work is so varied. Someone who starts with, say, the Bebb novels may, not liking them, conclude he or she has tried Buechner and never go on to something that might be just what that person needs, right when that person needs it—as was the case when, as a teenager, I came across A Room Called Remember at a library discard book sale.

For some people, the best place to start is with his novels, such as Godric. For others, the best place would be his memoirs, such as Telling Secrets. For others, the best place would be his biblical essays, such as The Alphabet of Grace. And still for others, it would be his sermons, such as Secrets in the Dark. For that reason, I almost always recommend Listening to Your Life, a day-by-day anthology of Buechner excerpts from all these genres. I tell people, “Just read around in there, see what gets your attention, and then go to the primary source from which it’s taken.” With the publication of Reading Buechner, though, I now have another resource to give to such people, one that explores Buechner’s life and background as well as the broad themes of his work.

Helpfully, the book is divided into sections for Buechner’s work as memoirist, novelist, popular theologian, and preacher. In each section, Munroe focuses on two to four recommended works. One need not agree with all the author’s choices (I think The Final Beast and Brendan are slightly better novels than The Son of Laughter, for instance). The narrowing allows Munroe to more comprehensively analyze each category. At the end of each section, he lists Buechner’s works in each category into the “essentials” and “others.” Again, these categorizations come with no pretense of inerrancy, but they will help guide new readers into what to explore first.

Strange Pentecostal

The book concludes with some provocative assessments of Buechner as he relates to contemporary evangelicalism. Munroe interacts with several of us in the evangelical tradition who love Buechner, while acknowledging that he doen’t belong to us. He then differs from the standard view that Buechner is a mainline Protestant whose work can be loved and appreciated by evangelicals, noting how discordant Buechner often was and is from the standard liberal Presbyterianism of the 20th century, much less that of the 21st. Instead, Munroe places Buechner where I would least expect to find him—in the category of Pentecostalism.

The staid and affluent New England intellectual as a Pentecostal is an image that, I’ll admit, at first made me laugh out loud. But then Munroe makes his case, pointing to the importance of subjective experience in Buechner, the transcendence of post-Enlightenment rationality, the place of the spirit-world. For a minute or two I wondered, Am I a Pentecostal too? I concluded, quickly, that the answer is no, but that I should pay more attention to Pentecost itself.

Buechner doesn’t fit the standard categories. Perhaps that’s why Buechner has been able to speak to so many of us from so many different theological and experiential tribes.

Munroe tells us that he is speaking partly tongue-in-cheek, but he makes his point: Buechner doesn’t fit the standard categories. Perhaps that’s why he’s been able to speak to so many of us from so many different theological and experiential tribes. He doesn’t expect us to adopt him, nor does he expect us to merge ourselves into some movement led by him. He just expects us to listen to him, and to know that, whether he’s right or wrong at any given point, he’s not selling us anything. He’s bearing witness, truthfully, as he sees it. And that’s why so many of us who may not agree on anything else find our eyes welling up with tears as we read the crypto-Pentecostal, halfway-evangelical, conflicted mainliner who wrote to us from Vermont.

If you love Buechner, this book will help you benefit even more from him. If you don’t know Buechner, this book will introduce you. If you’ve dismissed him, this book might change your mind. Reading Buechner listens to his life, to help us to listen to ours, and, more importantly, to lay down our lives and find ourselves in the life of Another.