An illustration by fourth-century church father Athanasius of Alexandria came to mind as I read Russ Ramsey’s Rembrandt Is in the Wind: Learning to Love Art Through the Eyes of Faith. In his On the Incarnation, Athanasius compares the image of God in fallen humans to a portrait that has been “effaced by stains from without.” He explains that because of the damage sin inflicted on humanity, God’s supreme work of art, the second person of the Trinity had to become a man to restore his likeness in us. The Word, who is the image of the invisible God, came to earth to sit again so that his “portrait could be renewed” (On the Incarnation, chap. 14).

But God didn’t start with a blank canvas when it came to redemption. He loved his image in humanity too much to discard us and start from scratch. As Athanasius puts it, “For the sake of the picture, even the mere wood on which it is painted is not thrown away, but the outline is renewed upon it.” Fallen human beings are damaged masterpieces, still displaying the likeness of our Creator at certain angles and in the right light. Though we’re tattered and smudged by sin, selfishness, and mortality, we still look like him. And this resemblance shows up whenever we stand for truth, strive for goodness, or create and celebrate beauty.

Ramsey, an art-lover and pastor at Christ Presbyterian Church in Nashville, Tennessee, believes beauty in particular has a power “to awaken our senses to the world as God made it and to awaken our senses to God himself” (14). The fact that believers and unbelievers alike are capable of producing beauty means that God works through otherwise unqualified image-bearers to “reveal his glory”—even amid their misfortunes, moral failings, and mental struggles. And if there’s anywhere we can easily find these types of brokenness, it’s in the history of art and the lives of those who create it.

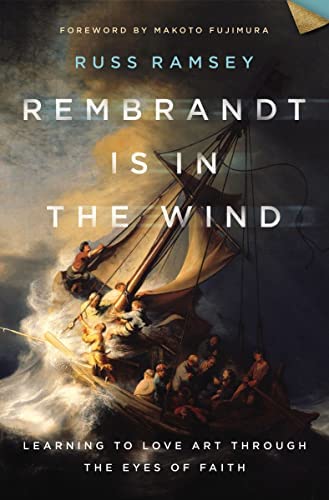

Rembrandt Is in the Wind: Learning to Love Art through the Eyes of Faith

Russ Ramsey

Rembrandt Is in the Wind: Learning to Love Art through the Eyes of Faith

Russ Ramsey

The book is part art history, part biblical study, part philosophy, and part analysis of the human experience; but it’s all story. The lives of the artists in this book illustrate the struggle of living in this world and point to the beauty of the redemption available to us in Christ. Each story is different. Some conclude with resounding triumph while others end in struggle. But all of them raise important questions about humanity’s hunger and capacity for glory, and all of them teach us to love and see beauty.

Finite Genius Drawing from Infinite Beauty

With vivid storytelling, Ramsey introduces us to nine great painters and sculptors whose complicated biographies illustrate how even in our fallen state, human beings mingle beauty with futility. Michelangelo carves his six-ton magnum opus David while ignoring cracks in the marble that mirror his own sexual shame. Caravaggio’s brush brings the Bible to life while his temper and intemperance deal death by night. Van Gogh fills his canvasses with peace and light while a storm of self-doubt and depression darkens his heart. Rembrandt’s most immortal painting falls prey to thieves and is lost in the winds of time. And Lilias Trotter sacrifices her art career to serve and evangelize the poor in an African desert.

These artists and their work reveal how God sees all of his image-bearers: “fully exposed in our shortcomings,” in our private torment, or in our subjection to decay. Ramsey sees in van Gogh’s Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear a picture of our “spiritual and relational poverty.” (For those who don’t know, van Gogh famously cut off his own ear during a paranoid frenzy and gave it to a prostitute.) This painting of a man at his lowest moment is a faithful depiction of our “shame and need for rescue,” even as we, like the anguished Dutch master, refract God’s brilliance in our flawed efforts to bring forth beauty.

Artists may dazzle us with their talent, but even the greatest genius is finite. Through the secret lenses that enabled Vermeer to paint with eerie precision, Ramsey sees a humble dependence on others, a “borrowed light” that proves none of us is self-sufficient. We need not only God but one another, and even geniuses depend on someone to make their paintbrushes. Without the Paris studio Frédéric Bazille provided for his fellow artists, the world might never have learned names like Degas, Renoir, or Monet. These men would have remained penniless and obscure. Sheer talent was not enough for them, and it’s not enough for any of us. We need help.

Artists may dazzle us with their talent, but even the greatest genius is finite. Ramsey sees a humble dependence on others, a ‘borrowed light’ that proves none of us is self-sufficient. We need not only God but one another.

Ramsey succeeds in making these points while also making art history read like a novel. His colorful retellings of the lives of biblical characters and the painters who gave them faces will inform and move you. For too many people, art museums are places of boredom and bewilderment. We wander from hall to hall admiring canvases but unsure of the meaning their makers wanted to convey. This book will teach you to see life within each frame, stories worth telling, and human struggles that reveal as much about us as they do about long-dead impressionists.

It’s also noteworthy that Ramsey chose to celebrate artists whose work to some extent imitates creation. All the painters and sculptors he profiles produced recognizable scenes and portraits, whether stark and lifelike or stylized and luminous. Not everything called “art” today is beautiful. Works like Onement VI, My Bed, and Piss Christ range from baffling to blasphemous. The late philosopher Roger Scruton chronicled this descent and pled with viewers to reclaim an older, nobler understanding of art and architecture. And while Ramsey doesn’t wade into that debate in this book, there are signs he shares Scruton’s distaste for much of modern and postmodern art.

Recovering Beauty

Rembrandt Is in the Wind also challenges Christians who have emphasized truth and goodness while neglecting beauty. Whereas religious art and art by religious people once inspired the world, today Christians have largely retreated to “the realm of personal conduct and intellectual assent” (9). This is a problem. Artist and author Makoto Fujimura asks in the foreword, “Why art?” (xiii), and Ramsey’s answer is that beauty gives full expression to truth and goodness:

Beauty takes the pursuit of goodness past mere personal ethical conduct to the work of intentionally doing good to and for others. Beauty takes the pursuit of truth past the accumulation of knowledge to the proclamation and application of truth in the name of caring for others. Beauty draws us deeper into community. We ache to share the experience of beauty with other people, to look at someone near us and say, “Do you hear that? Do you see that? How beautiful!” (9)

Maybe most importantly, beauty is fragile. Consider the ephemeral nature even of works of art we treat as immortal—Michelangelo’s David, which will one day topple, da Vinci’s Mona Lisa, which is kept climate-controlled to slow its decay, or even Notre-Dame cathedral, which went up in flames three years ago as the world watched. Ramsey reminds us that all the greatest human works of beauty will eventually succumb to corruption. Indeed, his title alludes to the fact that many, such as Rembrandt’s The Storm on the Sea of Galilee, already have. No one knows whether this masterpiece, cut from its frame by thieves 32 years ago, still exists. It’s “in the wind”—maybe forever.

This would seem to be our fate too. The artists Ramsey profiles, like their art, were tossed by storms of spiritual and bodily corruption. Their human frailty and faults obscured the beauty they painted and the beauty of God’s image in them. But the Savior asleep in the stern of Rembrandt’s boat can calm storms. For Ramsey, it’s no coincidence that Jesus shows up in so many great works of art. The human quest for beauty is in many ways a quest to transcend our sad condition—to not only make but also manifest a glory that will last. That means if we ourselves are images, we owe it to an artist. And if he hasn’t put down his brush yet, it’s good news, indeed.