There’s a long history of the rise and demise of scholars: gifted, bright, and erudite but, gradually chafing at the constraints of divine revelation and ecclesial confession, some intellectual stars begin to wander. From Pelagius (354–420) to Charles Augustus Briggs (1851–1913) and beyond, they rise from within orthodoxy, only to exit its margins.

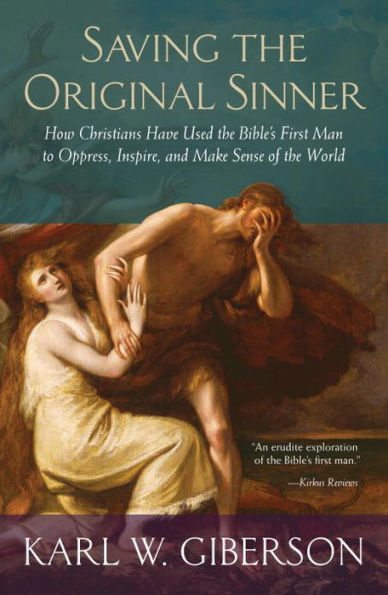

Karl Giberson’s Saving the Original Sinner: How Christians Have Used the Bible’s First Man to Oppress, Inspire, and Make Sense of the World is a classic example of controversial writing by a departing academic. Described as a “former evangelical,” Giberson taught for 27 years at Eastern Nazarene College in Quincy, Massachusetts, before moving (under pressure) to teach science and religion at Stonehill College in Easton, Massachusetts. A guest lecturer at numerous Christian colleges—including Biola, Calvin, and Wheaton—Giberson has more recently taught at Gordon College, and was a regular contributor at BioLogos. He’s no stranger to the evangelical world, having labored within it for decades as an apostle of evolutionary thought.

Giberson’s prologue casts academics who challenge the existence of a historical Adam as victims. Citing Galileo Galilei (1564–1642) and Isaac La Peyrère’s (1596–1676) sufferings at the hands of “heresy hunters,” he reminisces:

In midwinter 2011 as I started on this book, another scholar, this time an American Calvinist named John Schneider, was summoned by heresy hunters and interrogated for the same beliefs that had threatened La Peyrère. The heresy was the status of the biblical Adam. (ix)

The introduction is at times poignant. Reflecting on a visit to the Creation Museum in Petersburg, Kentucky, Giberson recounts seeing “wholesome, loving Christian families like mine had been,” wondering whether “these young people would have faith crises in college, as I did” (2). He muses that faith in a heaven “is a flickering message of hope to me, holding out the possibility that I may once again see my mother, who remains daily in my thoughts despite having passed away years ago” (4).

These reflections are a healthy reminder that those who disagree with us also suffer. Controversy ought not dim our compassion.

Caricaturing Truth

While Giberson includes a personal narrative of his academic suffering, he also provides a scathing, sustained criticism of creationism, biblical inerrancy, belief in a historic Adam and Eve, the doctrine of the fall, and original sin. Particularly anathema to Giberson is the idea that presuppositions drive the reading of evidence in origins, so that “if you start by rejecting God’s infallible wisdom in the Bible and instead put your faith in fallible human reason, you end up with evolution, the big bang, despair, moral relativism, and eternity in hell” (5). Giberson’s gloves are off:

The oft-repeated claim about starting assumptions is both wrong and offensive. It’s a cheap debating trick. Like most Christians who no longer believe in Adam and Eve, I did not come to that belief by rejecting the Bible and then forcing whatever changes followed from that as though being anti-Bible was a reliable way to generate falsehoods. I came to it by trying to reconcile science with that Bible. (6)

Saving the Original Sinner: How Christians’s Have Used the Bible’s First Man to Oppress, Inspire, and Make Sense of the World

Karl Giberson

Saving the Original Sinner: How Christians’s Have Used the Bible’s First Man to Oppress, Inspire, and Make Sense of the World

Karl Giberson

Giberson calls for a renewed conversation between science and Christianity, and for more open engagement with new scientific discoveries, even when they threaten central doctrines. Christians should not be made to choose between their faith and their understanding of the universe. Instead, as Giberson argues, they should follow in the once robust tradition of exploring science openly within the broad contours of Christian belief.

Giberson’s claims here are caricatures: few evangelicals believe individuals commonly experience a sudden, wholesale exchange of foundational intellectual commitments and then crisply set about reassessing reality. Even in sanctification and its implications for understanding, changes often take place over a lifetime; the same is true in theological declension.

Nonetheless, even slow shifts in basic commitments have profound implications for our understanding of reality. Giberson’s own narrative arguably presents such a story of change in both foundational beliefs and understanding of “the evidence.” His “faith crisis” as a college student was integral to his pursuit of reconciling science and Scripture, from which he moved to a rejection of divine inspiration, infallibility, and inerrancy.

College Faith and Doubt

Giberson’s irritation with the concept of basic beliefs and their implications connects with another aspect of Saving the Original Sinner. Complaining of evangelical “heresy hunts,” he also disparages the place of confessional statements in institutional life.

Why? The fact is some—perhaps all—of the individuals Giberson casts as victims challenged and contradicted commitments to which they’d subscribed at their hiring. This doesn’t mean in every case they were entirely to blame—some schools quietly allowed wider latitudes than their stated creeds, which in the end is fair to no one. But Giberson’s complaint is broader: it’s oppressive to college professors, women, and gay marriage to pursue commitment to Scripture as God’s Word. A historical Adam, he contends, is not only the death of academic freedom, it’s an instrument of an oppressive social order. Where belief in the fiction of Adam may once have been acceptable, that time is now past.

Much of the remainder of the book is occupied with criticisms of Scripture and historic Christian orthodoxy on human origins, the fall, and sin:

- God is described as giving arbitrary commands: the “mysterious talking serpent made sure Eve had a chance to think about the odd prohibition” (17).

- Giberson exhibits a Marcion-like distaste for the God of the Old Testament, obscuring the redemption narrative: “[God] is enraged . . . [and] grants no immortality option to the first humans. . . . children become the only hope that one will not have lived in vain” (19).

- The gospel promise of Genesis 3:15 is ignored.

- In the flood account, Noah “is apparently satisfied that he and his family will survive . . . makes no effort to mitigate God’s wrath . . . or sneak any of his friends and neighbors aboard the ark.”

- Giberson ignores God’s patience with mankind and Noah’s role as a preacher of Christ (1 Pet. 3:19), later echoing as “plausible” Richard Dawkins’s claim that God is a “vindictive, bloodthirsty ethnic cleanser” (24).

Turning to the New Testament:

- Giberson describes Jesus’s message as “exclusively for the lost sheep of Israel and not for the despised Gentiles” (39), revealing an ignorance of the Gospels (e.g., John 4; Matt. 8).

- Jesus appears as a mere man, with “ambiguous” teaching characterized by “vagueness” (38–39).

- Paul becomes a theological innovator who develops the idea God loves and redeems all of humanity, partly because he “felt free to use the Adam story in any way he wanted” (39).

Not only is there no Adam for Giberson; there’s no Immanuel.

Beyond the canon, Giberson continues his history of thought on origins. Some is debatable and too much is caricatured and plagued by poor historiography, relying heavily on secondary sources. Even following Giberson’s premises, there’s significantly better scholarship in the field (see David Livingstone’s Adam’s Ancestors: Race, Religion, and the Politics of Human Origins).

Wandering Stars

Karl Giberson’s story is a cautionary tale for ourselves—an occasion to humbly ask God to examine and convict us of where our priority and authority lies (Ps. 139:23–24). While the scriptural terms “heresy” and “blasphemy” are rarely used in present-day evangelicalism, Giberson has moved into the realm where these sober descriptors find warrant: “These people blaspheme all that they do not understand . . . [they are] wandering stars” (Jude 10–13).

I pray he comes back.