Is the church slowly but surely dying, at least in Western societies? According to the “secularization” paradigm, Christian faith was once endorsed by the majority in many Western countries but has now become a minority religion; moreover, this fact is closely tied to the process of “modernization,” a seemingly irreversible process. Such a decline can be illustrated by striking figures: church attendance on Sunday has diminished from about 50 percent of Britain’s population in 1851 to around 9 percent in 2001 (9).

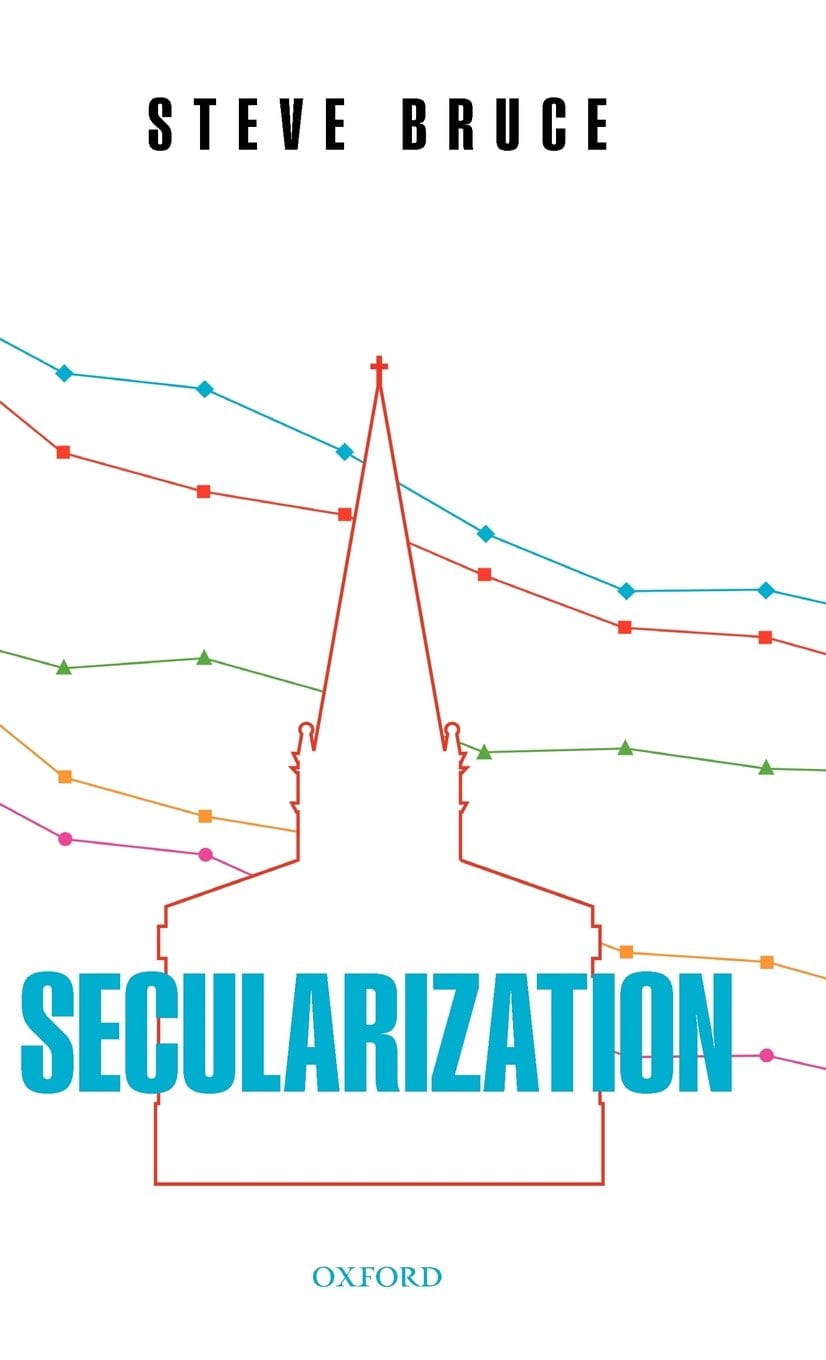

However, numerous objections have been raised against the secularization theory. Steve Bruce resolves in Secularization: In Defense of an Unfashionable Theory to systematically address and refute them. Here are two examples of common objections against the theory of secularization and a summary of how Bruce—professor of sociology at the University of Aberdeen—responds:

- Proponents of the secularization theory, it is said, exaggerate the prevalence of Christianity in pre-modern times, hence artificially creating a huge decline since then; in reality, human beings in the Middle Ages were like us, both pious and impious. Bruce replies by pointing out the massive testimony of “the cathedrals, the monasteries and convents, the sums left to religious causes in wills, Easter Mass attendance, the popularity of shrines and the relics of the saints, and the constant reference to Christian themes in every form of literature and popular discourse” (79–80). Furthermore, it would be difficult to argue that most of the population was constrained during previous centuries to adopt imposed religious views and to pretend; rather, Christian belief was truly popular.

- The decrease in church attendance, according to other opponents, does not signify a general loss of faith; rather, it is a symptom of the fact that Christian piety has been redirected into other forms: either an individual (rather than public) spirituality, or a sort of “vicarious religion” (a minority is religiously active on behalf of a much larger number), or even simply “popular” or “folk” religion that does not involve constant but only occasional church attendance. According to Bruce, scholars who contend these views have failed to show that they actually constitute durable alternatives to classical Christian piety (99).

Stimulating Read

Many challenges to the secularization paradigm correspond to intuitive counter-arguments. Regrettably but inevitably, this kind of apologia from Bruce results in a rather “defensive” tone that permeates the book; on the other hand, the more you initially disagree with the secularization theory, the more the book will prove profitable to you, insofar as it enables you to progress from intuitive ideas to scrutinized arguments and, if necessary, to change your mind.

While it is not possible here to discuss all the details of Bruce’s arguments, many of his refutations seem well-grounded in sociological considerations and supported by scholarly studies and statistics. At the very least, this study shows that many objections to the secularization paradigm are unable to seriously challenge the historical assessment.

That said, there remain countries where the paradigm does not seem to work entirely. The author acknowledges that “the USA is more religious than other industrial societies” (172). He explains this difference by (a) “large-scale migration from non-industrial countries with powerful conservative religious traditions” (172–173); (b) national diversity, due to “the federal and diffuse of [USA] polity,” in contrast to more centralized countries like the UK and France; as a result, fundamentalist organizations are freer to develop and promote their views. However, large immigration and liberty of opinion are common features of many secularized, industrial societies. If we have to remove concrete realities like immigration from the countries we study, are we still dealing with reality? According to Bruce, these factors mitigate the effects of secularization in the United States without obliterating the overall trend. This seems quite possible, and the United States is probably a secularized society to a great extent, but I wonder whether the paradigm sufficiently integrates the complexity of this country. At the very least, Bruce’s explanations here are not as convincing as in other chapters of his book. Similarly, the discussion about Latin America, especially Brazil, seems to me very short (186–187).

Christianity and the Gospel

Whatever the case, it is clear that the secularization theory points out reality: a few centuries ago, Christianity was a dominant religion with a huge influence in countries like France and England, whereas today, it is only a marginal phenomenon there. But the “spiritual interpretation” of these factual data is where many evangelicals will probably have the most questions. To what extent is the historical influence of Christianity a reliable witness of the actual spiritual effects of the gospel in the past? Can we equate the influence of the church and of the Bible on society, politics, literature, politics, philosophy, and so on with what we regard as the true effects of the gospel: transforming lives by spiritual renewal thanks to the faith in Christ? To what extent does church attendance help us in measuring actual faith?

Asking such questions is neither an attempt to denigrate religious practices of the past, nor to suggest that before Martin Luther the gospel was not preached at all. From a sociological point of view, church attendance is the object of scientific investigation and measuring. But from a spiritual point of view, evangelicals believe that people can attend church every Sunday, observe many rituals, and even hold sincere beliefs about God and Christ, without having grasped the grace of God and experienced a true conversion. This is a reality we know too well in our own churches.

Secularization: In Defense of an Unfashionable Theory

Steve Bruce

The decline in power, popularity and prestige of religion across the modern world is not a short-term or localized trend nor is it an accident. It is a consequence of subtle but powerful features of modernization. Renowned sociologist, Steve Bruce, elaborates the secularization paradigm and defends it against a wide variety of recent attempts at rebuttal and refutation.

In a word, we cannot simply equate the history of Christianity with the gospel. Admittedly, if most of the people who attended church in the past centuries have really experienced the new spiritual birth in Christ, then I am more than glad. But it stands to reason that things are not so simple, especially in view of the fact that Christianity was an official religion in many countries and that some pre-Reformation religious practices as well as post-Reformation liberal ideas have obscured the grace of the gospel. As a result, the number of actual believers of the past is probably less than the figures of church attendance suggest; consequently, the alleged decline of Christian faith is probably less significant.

In a sense, we could argue that today, we have returned to a situation akin to the pre-Constantine times and that for centuries, the official Christian faith created nominal Christians. There is nothing to regret in the fact that today, attending church is a personal choice based on authentic faith.

So are Western churches dying? Far from it; the fact that only a low percentage of the population in a country believes in Christ does not say anything about the vitality of the church. To take the example of a very secularized society I know well, Bruce mentions a study indicating church attendance has decreased in France from 23 percent to 5 percent between 1970 and 1999 (10). But this is certainly explained by the fact that many Catholics who called themselves “croyant mais non pratiquant” simply ceased to attend church. On the other hand, the number of evangelicals in (metropolitan) France since 1970 has grown from 50,000 to 460,000; the number of evangelical churches has grown from 769 to 2,068, and a new church is created in France every 10 days. Admittedly, this represents only a small percentage of the population, and it is clear that French society is very secularized—but thank God, the evangelical church in France is growing considerably.